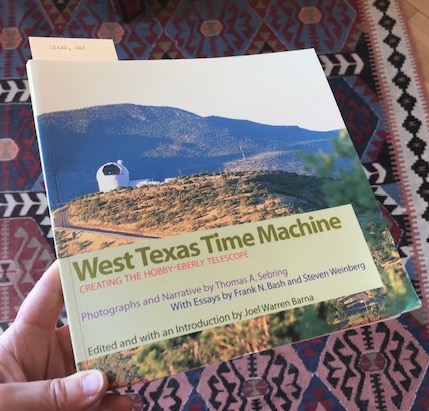

This Monday finds me in deep noodling, mainly on my Far West Texas book but also, Schritt für Schritt, my translation of Countess Paula Kollonitz’s memoir of her visit to Mexico in 1864.

Relatedly, herewith, from the archives (specifically, ye olde research blog Maximilian & Carlota ), are Henry R. Magruder’s woodcuts from his memoir of his visit some two years later: Sketches of the Last Year of the Mexican Empire. Magruder’s was one of the many memoirs that I read as part of my research into my novel based on the true story, The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire. Just as Kollonitz’s memoir has been bringing it all to mind so vividly, Magruder’s woodcuts provide a glimpse of the garden paradise that was once Mexico City— and so much more.

*

Published in 1868, Henry R. Magruder’s Sketches of the Last Year of the Mexican Empire is a rare and valuable record if the final year of Mexico’s Second Empire, a period roughly the same as the “French Intervention.” Magruder, an ardent Catholic, came to Mexico in 1866 with his father, the ex-Confederate General John Magruder.

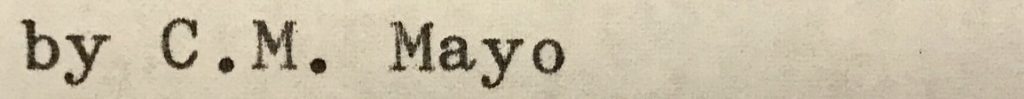

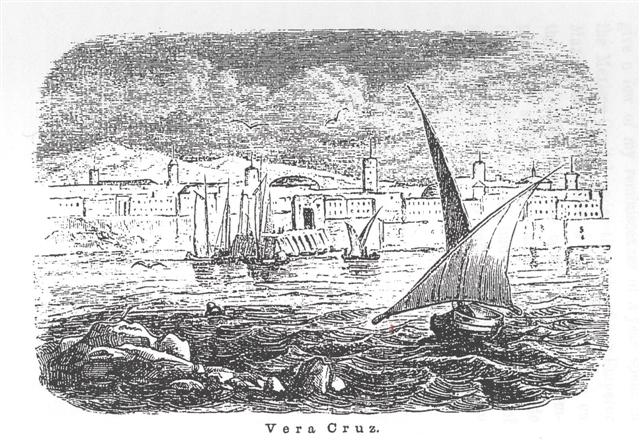

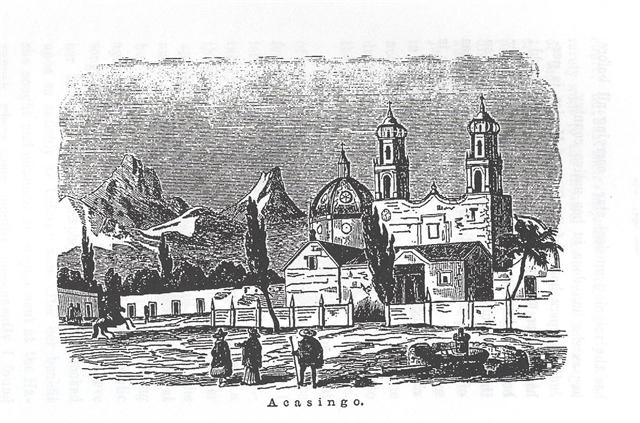

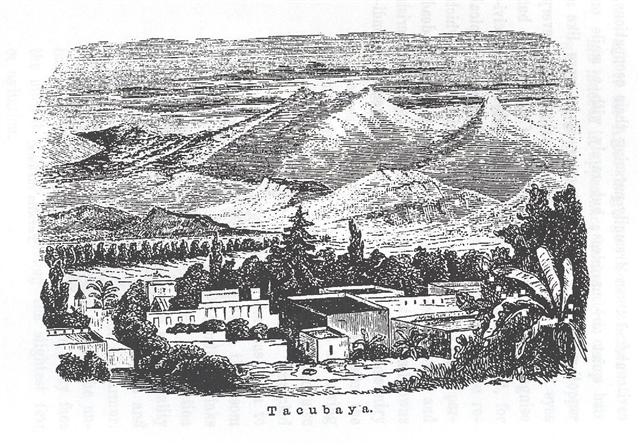

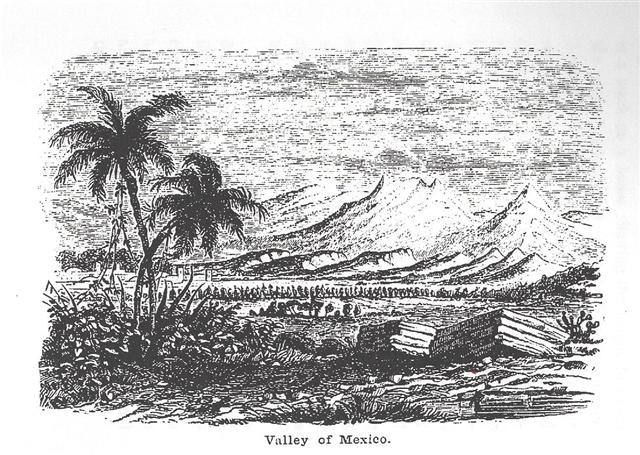

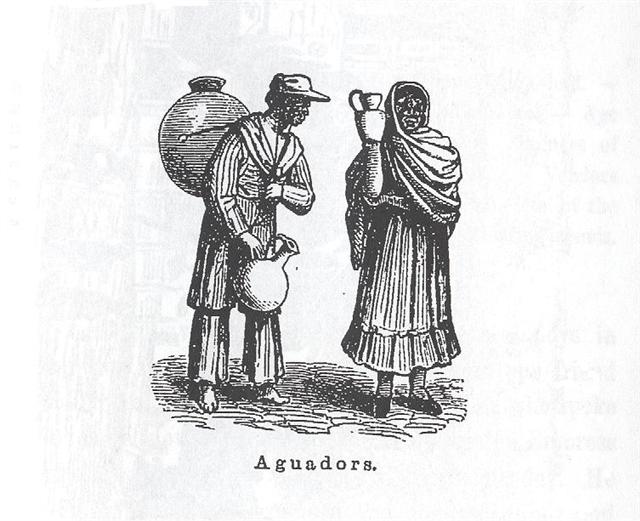

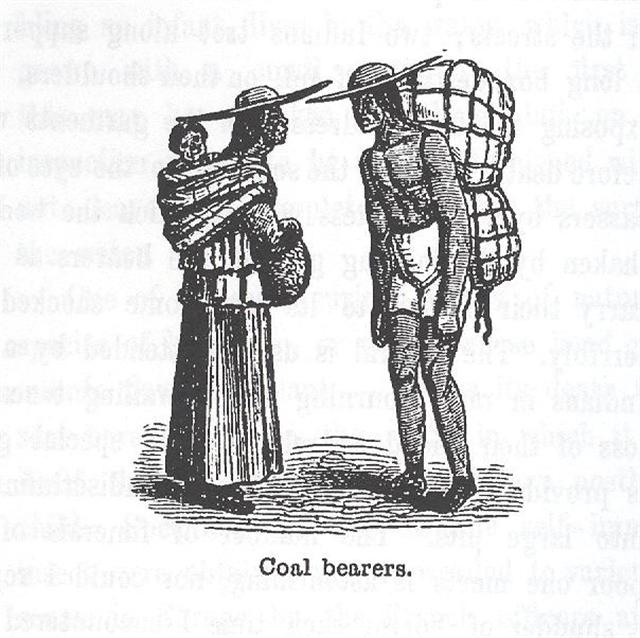

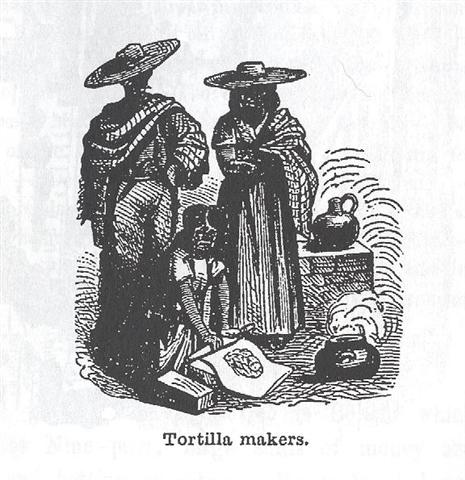

The illustrations are the author’s own woodcuts of five landscapes (Veracruz; Acasingo; Chapultepec; Tacubaya; Valley of Mexico;) and five portraits (Aguadors; Coal Bearers; Mexican; Ranchero; Tortilla Makers).

“In the course of the morning we entered the port of Vera Cruz, which town with its glittering Church-domes, dazzlingly white spires and many coloured houses, preseted from the distance the appearance of an eastern city. On nearer approach one is grievously disappointed. The scavaenger birds are protected and encouraged to frequent the place as they maintain the sanitary condition of the streets, they give a wierd appearance to the town and look like birds of ill omen, they fly all over Vera Cruz unmolested.”

“At eight in the evening we stopped at a village called “Acasingo” and heard that a diligence [stagecoach] had been plundered that morning, and if we persisted in continuing our journey that night, should certainly be attacked; what the crowd of Mexican standing around, and all talking at once, and not one of us understanding what was said, we foolishly allowed ourselves to be pursuaded by the rest of the travellers, to remain the night in the place, we alighted and before we had time to reconnoitre, the stage had driven off and we were forced to remain whether we would or not. On searching for an inn we were suprised to find that as Acasingo was not a regular halting place, such an establishment as an hotel did not exist; fortunately we found some people who offered us one large bedless room for our party; the apartment we had obtained must in former years have been very fine, the walls being still covered with traces of old frescoe paintings, it possessed a very fine balcony overlooking the “Plaza” or Square, which, although it may not even possess enough houses to surround it, every Mexican town contains. We found there were shutters, but no glass to the window, and were obliged to make up beds for the ladies on the chairs, the geltemen of the party sleeping on the floors…”

“From the entrance of the Church [Villa de Guadalupe] I had a view of the surrounding scenery which will never be obliterated from my mind, in one word it was gorgeous and magnificent. In the distance the fair Capital, its many spires and dome glittering in the midday sun, surrounded by the blue lakes, and the plains overgrown with the wierd looking Maguey plants; far away in the distance the beautiful snowy mountains, of which one never wearies, bounded one side of the valley, whilst on the other the park and grounds of the Emperor’s summer residence the famous Chapultepec stood in bold relief against the distant blue mountains…”

“The Paseo is about two miles in length— only the upper division of which is used by carriages the lower one being almost exclusively occupied by those on horseback. After leaving the crowded drive the road becomes pretty and is shady all the way, and the surrounding scenery most lovely, arriving at the end of the Paseo the rider finds a most romantic convent: “La Piedad,” the road here divides into two, branching off into different directions, one of which leads to Tacubaya and the other to San Angel a small village in the mountains.”

“The climate of the valley of Mexico may be likened to a perpetual spring, little rain falls except in the months of July, August and September, and then usually in the afternoon between two and five o’clock, exercise can always be taken in the mornings. Sometimes the showers or “Aguaseras” [sic] as they are called are so heavy, that in a few moments the streets are flooded and impassable unless on horseback or on the shoulders of the Indians who during the season make a business of vcarrying people.”

“The City of Mexico is supplied with water from the mountains by means of two grand aqueducts, which terminate in the town in large and very handsome fountains, whence the “Aguadors” [sic] fetch the water in their earthen vessels. These aqueducts are almost in ruins and greatly need repair for at intervals the water may be seen trickling through crevices.”

“These wretched indians are generally not overly clean, and if one comes into close contact with them, it is advisable on returning home to shake one’s coat.”

“The nearer we approached Puebla the more crowded grew the road, and I then for the first time observed the picturesque dress of the Mexican “Rauchiero” [sic] which is composed of yellow leather, elaborately embroidered with silver and gold; the seams of the trousers are decorated with a row of gold or silver buttons, the sleevs of the short and jaunty jacket being trimmed in the same style, over the shoulder hangs gracefully a “serape,” a kind of large scarf fenerally of white and red tho’ all colors may be seen, on the head an enormous “Sombrero” or hat with a large brim also enriched with silver and gold is worn; the Mexican men generally ride on horseback and have the most magnificent saddles, the pommels of which besides being high are of solid silver, exquisitely chased and engraved.”

“In the place of bread a cake called “Tortilla” is generally eaten, in reality it is the bread of the country, it is made of corn-meal mixed with water until it has the consistency of paste, which is pressed between the cook’s hands to flatten it and afterwards baked; it has little taste and is generally heavy.”

*

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

Ignacio Solares’ “The Orders” in Gargoyle Magazine #72

More on Seeing as an Artist or,

The Rich Mine of Stories About Those Who “See” the Emperor’s Clothes

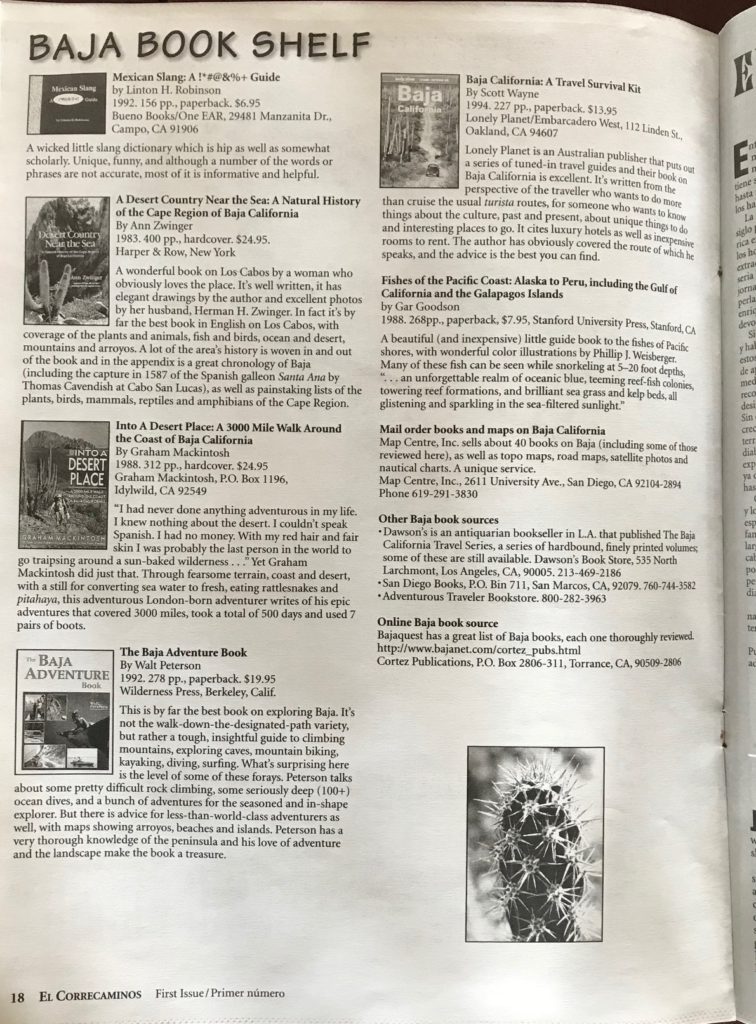

Reading Mexico:

Recommendations for a Book Club of Extra-Curious

& Adventurous English-Language Readers