This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

“I knew that there were many people on both sides [of the US-Mexico border] who were capable of a more nuanced understanding and wanted a better relationship between our countries. Those were my ideal readers. “—Michael Hogan

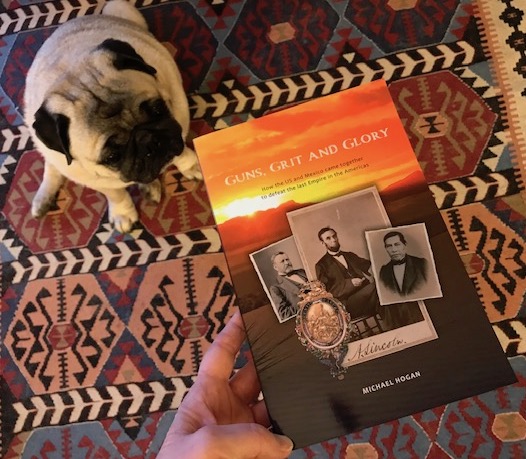

Michael Hogan has been publishing some of the most fascinating and important works on US-Mexico history that we have. I don’t say that lightly; for my historical novel, The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, I spent nearly a decade, in some of the very same archives, researching this period that he writes about in Guns, Grit and Glory: the French Intervention in Mexico, which allowed for Mexico’s Second Empire under Maximilian von Habsburg. This period overlaps, and in no way coincidentally, with the period of the US Civil War. Because governments and school boards have their political agendas, and of course time for teaching history to children and teenagers is limited, “the narrative” of such episodes that they learn is, by its nature, biased and severely truncated. Sometimes it just gets skipped altogether. So it sometimes happens that some episodes and actors and factors that are hugely important come to light decades, even a century or more later. But this light shines only if and when someone has had the burning curiosity, determination, skill, and perseverance, to dig out the evidence and then recraft a new narrative.

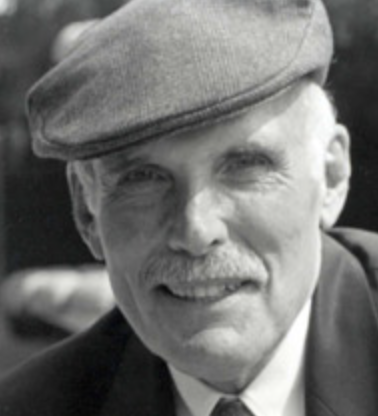

Michael Hogan is an American author of twenty-five books including the critically acclaimed The Irish Soldiers of Mexico and Abraham Lincoln and Mexico. He holds a PhD in Latin American Studies and is Emeritus Humanities Chair at the American School Foundation of Guadalajara. He lives in Mexico.

C.M. MAYO: What inspired you to write Guns, Grit and Glory?

MICHAEL HOGAN: In 2017 I wrote Abraham Lincoln and Mexico, a book that fully revealed for the first time, Lincoln’s support of Benito Juárez when the Mexican president and his Republican forces were driven from the capital by the invading French Army. They were forced to fight an unequal war with poorly clothed, sometimes barefoot, and poorly armed retreating soldiers. I discovered that besides moral support, Lincoln also allowed Mexican agents to raise funds in the US to help feed those troops and provide medicines. But many questions remained. How did Juárez avoid capture by the combined French forces? How did he acquire uniforms and boots, grooved cannons, and other sophisticated weapons for his men? How did his soldiers develop the expertise and training to use them effectively? How did a small retreating army overcome what was the most powerful military force in the world?

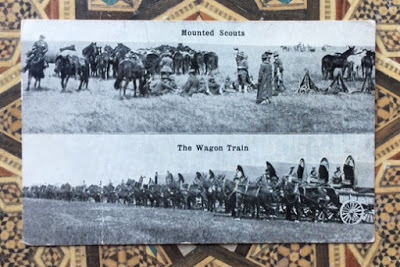

Most of these questions plagued me when I finished that book, although I had some clues. One was an article written by the late historian Robert Ryal Miller about the American Legion of Honor, a group of US volunteers who joined the Mexicans in their fight. In fact, members of this group rescued Juárez when he was in mortal danger of being captured and killed.by French forces in Zacatecas. Another was the discovery that, at the end of the Civil War, African American soldiers from the US Colored Troops joined the Mexican Army after being mustered out of the Union Army at the end of the Civil War. By 1866, there were over 3,000 US volunteers helping the Juárez forces, several were former officers and non-coms, others were sharpshooters and cannoneers. All were tested combat veterans. That story had not really been told, nor the tremendous amount of funding provided by the sale of Mexican bonds (worthless if the war was lost) which Mexican Consul Matias Romero was able to sell, thereby raising in excess of 15 million dollars.

C.M. MAYO: As you were writing, did you have in mind an ideal reader? If so, how might you describe the ideal reader for Guns, Grit and Glory?

MICHAEL HOGAN: I wrote it during the period when there was quite a bit of tension between the US and Mexico. I thought it might be a valuable contribution to show that there was a time when the US and Mexico came together to fight for a common cause. My ideal reader was someone who was open to have a new (but researched-based) understanding of US-Mexican relations. For this reason, there is also a Spanish edition. My thirty-plus years in Mexico had convinced me that there were misgivings and misunderstandings of the US-Mexican relationship on both sides of the border. Many Mexicans still resented the invasion of 1846 and loss of their northern territories. Many people on the US side were too willing to blame Mexico for the current migrant crisis on the border. Yet I knew that there were many people on both sides who were capable of a more nuanced understanding and wanted a better relationship between our countries. Those were my ideal readers.

C.M. MAYO: Researching a book like this requires extraordinary organizational skills. Can you talk a little bit about your working library and how you keep track of the books you read / consulted? And how do you keep track of articles, both on-line and on paper? And what were some of the things you did for this book that worked especially well for you?

MICHAEL HOGAN: I was lucky that I was teaching history at an institution that gave me free access to several academic subscription services which I could download and print. I am also fortunate in that my wife, Lucinda Mayo, and I have accumulated a large personal library over the years of over 5,000 titles in both English and Spanish. So, for many sources, I kept track the traditional way, with markers and notes, and separate file folders for each theme, battle, or personage. Since the COVID crisis had not yet struck I was also able to access archives in Chihuahua, where Juarez had his headquarters, and the archives of the Banco de Mexico in the capital, where Romero’s papers were stored. He had been the treasury secretary and head of the bank under Porfirio Díaz.

C.M. MAYO: What was the biggest surprise that you came across in your research?

MICHAEL HOGAN: There were several. The first was that many of the details I found were not in the Archivo de la Nación but rather in the Banco de Mexico. I think perhaps a decision was made to keep them there so that Porfirio Díaz could claim his great victories were without any significant help from the gringos.

Another surprising discovery was that trustworthy French eyewitnesses claimed they observed over 10,000 Americans at the Battle of Querétaro whereas Professor Miller only credited 300 or so in the American Legion, and Romero said there were only 3,000 Americans total, which included the African American soldiers.

However, it was unlikely that the French were wrong; besides theirs was a primary source. So, secondary sources, a Mexican consul who was not present and a US professor writing a century later, must have been mistaken. How to resolve the dilemma?

Quite by accident, I discovered purchase invoices for several thousand Union uniforms in the Mexican military archives. There was the answer. The thousands of bluecoats that the French saw on the hills of Queretaro were mostly Mexicans in surplus US Army uniforms!

C.M. MAYO: What was the most challenging aspect of writing this book?

MICHAEL HOGAN: So much of what was occurring doing those years was clandestine. The US could not openly aid the Mexicans because to do so would alienate the French who might then join up with the Confederacy. Besides the French were historic allies who helped the US gain its independence. On the Mexican side, Romero representing Juárez, would have to offer foreign investors in those high-risk Mexican bonds either parcels of land, or mining concessions, or other significant incentives if the government were to default. This fact needed to be kept secret lest Juárez be accused by his own people of signing away large swaths of Mexican territory and the patrimony of the next generation. In fact, there were defaults, and by the end of the next decade over 20 percent of Mexican territory was owned by foreigners.

C.M. MAYO: What has most surprised you about its reception?

MICHAEL HOGAN: On the positive side, I was both surprised and delighted by the critical acclaim especially from academics whose work I highly regard such as William Beazley at the University of Arizona, John Mason Hart at the University of Houston, Don Doyle at the University of South Carolina, Brigadier General (Ret.) Clever Chávez Marín, editor of Estudios Militares Mexicanos, and others. Sadly, although the book received quite a bit of positive critical acclaim, the book’s release in March of 2020 at the beginning of the COVID pandemic ensured that all my in-person events were canceled. Three major events (which in the past had garnered audiences of several hundreds) in Chicago (Union League), Lake Chapala (Open Circle), and a historical society in Texas were all postponed or canceled. Two were rescheduled for the fall, and then canceled again because of COVID resurgence. I am hopeful that the first in-person event scheduled for this spring will take finally take place, and also that this interview and on-line reviews will encourage new readers.

C.M. MAYO: For readers who are just getting to know Mexico, what would be your top three book recommendations?

MICHAEL HOGAN:

1. The Course of Mexican History by Michael Meyer and William Sherman. A highly readable text which tells the history of Mexico from pre-Columbian times to the present. With a rich bibliography for those who wish to delve deeper.

2. Mexico: Biography of Power by Enrique Krauze. A compelling history about the evolution of power politics in Mexico from the origins of the nation-state after the War of Independence to the present day.

3. The Labyrinth of Solitude by Octavio Paz. Insights into the Mexican character, origins of the macho culture, and the evolution of post-colonial bureaucratic elements in government. A controversial exposé by a Nobel Prize recipient of his own people and their character.

Visit Michael Hogan’s website at http://www.drmichaelhogan.com/books/the-irish-soldiers-of-mexico.php

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

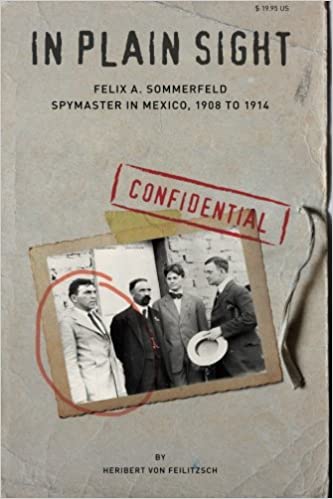

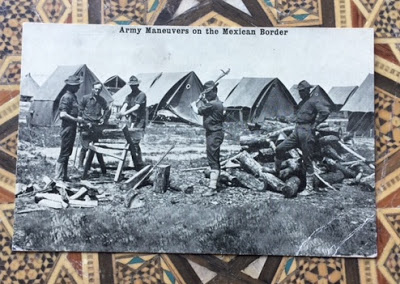

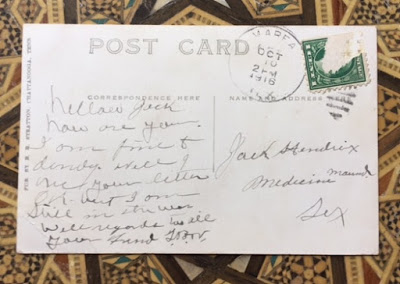

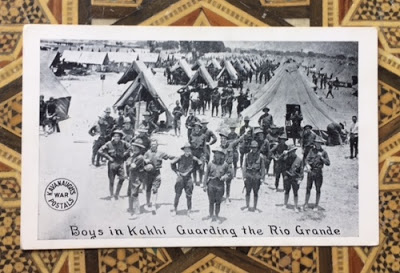

From the Archives: My Review of Heribert von Feilitzsch’s

In Plain Sight: Felix A. Sommerfeld, Spymaster in Mexico, 1908-1914