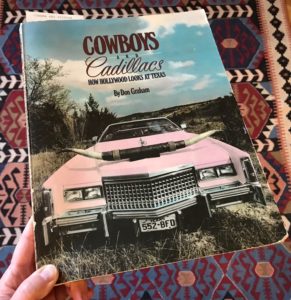

This blog posts on Mondays. This year, 2021, I am dedicating the first Monday of the month to Texas Books, in which I share with you some of the more unusual and interesting books in the Texas Bibliothek, that is, my working library. Listen in any time to the related podcast series.

Without question the iconic image of Far West Texas in the 20th century and into our day in the 21st is that of James Dean in character as Jett Rink, sprawled in the back of an open automobile. Unless you were born yesterday, or grew up in, oh say, the highlands of Papua New Guinea, surely you will recognize it:

It is a still from Giant which was filmed on a stage-set, no longer extant, on a ranch just outside of Marfa, Texas. Here’s one of the many movie posters which incorporate the image:

And here’s a more recent DVD package cover:

And don’t think you can get away from James Dean-Jett Rink if you go to Marfa! Last time I was there, Giant was playing nonstop in the lobby of the Paisano Hotel, and there were postcards galore for sale featuring the James Dean-Jett Rink image. In Alpine, the town next-door (in Far West Texas next-door would be a half hour’s drive), the bookstore incorporates James Dean / Jett Rink into its logo:

The movie Giant, based on Edna Ferber’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, and starring James Dean, Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson, and directed by George Stevens, was a smash hit in 1956, and to this day it remains, in the words of film historian Don Graham, “probably the archetypal Texas movie; it contains every significant element in the stereotype: cowboys, wildcatters, cattle empire, wealth, crassness of manners, garish taste, and barbecue.”

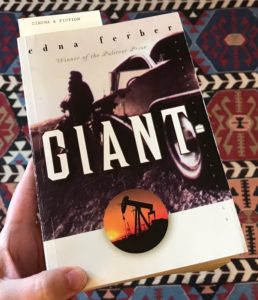

Here’s my copy of Ferber’s novel:

The movie Giant now seems integral to the very weave of Texan cultural identity, yet when it was being filmed, many Texans who were familiar with the novel and its vociferous condemnation of prejudice and segregation, made threatening noises. One Texan told a Hollywood columnist, “If you make and show that damn picture, we’ll shoot the screen full of holes.”

For her saga of the family of cattle barons (Bick and Leslie Benedict, in the movie played by Rock Hudson and Elizabeth Taylor) versus the upstart oilman (Jett Rink, played by James Dean), Ferber did her research—that would be another post. However, Ferber was no Texan, she was a liberal Jew originally from the Midwest, resident in Manhattan, member by the way of the Algonquin Roundtable, and she had made a career writing blockbuster ready-for-Hollywood novels. Texans generally came to embrace the movie Giant, but at the time the novel came out in 1952, the Texan attitude was more, Who was this highfalutin’ person to judge, never mind attempt to write about, Texas? Quoted in J.E. Smyth’s Edna Ferber’s Hollywood, one reader’s letter-to-the-editor of the Ladies Home Journal, which had serialized the novel, sputtered: “I thought I had heard very misconception of Texas and its people and every form of ridicule possible to small minds, but you have left me speechless with astonishment— such colossal ignorance I have never encountered.” Another reader claimed there was no racism in Texas, however, if any Texan “made the mistake of marrying a Mexican, she certainly would not be entertained in the living room”— and so on.

Apart from the James Dean scenes— all of them— the scene from the movie Giant that has echoed over the decades is the diner scene, also known as The Fight at Sarge’s Place. In Ferber’s novel, Mrs. Benedict (the cattle baron’s wife, played by Elizabeth Taylor), with her Mexican daughter-in-law and grandchildren, is refused service in a roadside café. From the novel:

“You can’t be talking to me!” Leslie said.

“I sure can. I’m talking to all of you. Our rule here is no Mexicans served and I don’t want no ruckus. So— out!”

In the movie, however, Bick Benedict (Rock Hudson) is with his wife Leslie (Elizabeth Taylor), the Mexican daughter-in-law, and the grandchildren. They have been seated, but when the owner, Sarge (played by Mickey Simpson) rudely refuses service to a Mexican family that came in after them, Bick protests. A slugfest with Sarge ensues, and the now elderly Bick ends up sprawled on the floor, unconscious. Sarge grabs his sign from the wall behind the cash register and throws it on top of Bick:

WE RESERVE

THE RIGHT

TO REFUSE SERVICE

TO ANYONE.

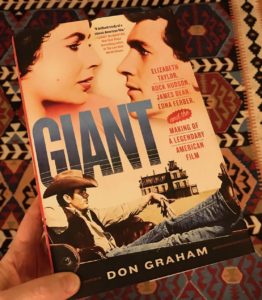

So it was in certain parts of the United States in the days before the Civil Rights Act— and that sign, in the words of Don Graham, “was the most famous emblem of racial discrimination in that era.” (Graham, Giant, p. 198)

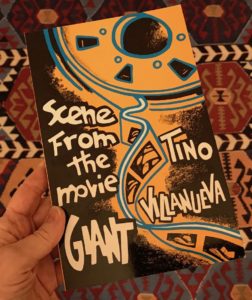

Side note: Here’s my copy of Scene from the Movie GIANT by Tino Villanueva (Curbstone Press, 1993), an exquisite book-length poem about a 14 year old Mexican American boy watching that very scene in a movie theater.

From Tino Villanueva’s Scene from the Movie GIANT:

That a victory is not over until you turn it into words;

That a victor of his kind must legitimize his fists

Always, so he rips from the wall a sign, like a writ

Revealed tossed down to the strained chest of Rock Hudson.

And what he said unto him, he said like a pulpit preacher

Who knows only the unfriendly parts of the Bible.

After all, Sarge is not a Christian name. The camera

Zooms in:

WE RESERVE

THE RIGHT

TO REFUSE SERVICE

TO ANYONE

Here’s my copy of Giant: Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean, Edna Ferber, and the Making of a Legendary American Film by Don Graham:

Writes Don Graham in his history, Giant:

“[Director George] Stevens held a strong belief in racial equality, and he meant Giant to tell a story that would compel viewers of the film to consider their own prejudices instead of blaming them on other people. In Stevens’ mind, Giant would prompt people to examine their own hearts.” (p. 198)

George Stevens’s own heart had been opened as by a chainsaw.

In the decade before World War II he had been turning out feature films starring such legends as Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn, Betty Grable, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rodgers, James Stewart and Cary Grant. Then, to do his part in World War II, he set his career aside. For the US Army Signal Corps’ motion pictures unit, he filmed the Normandy Invasion, the liberation of Paris, and the liberation of Nazi concentration camps. Writes Graham:

[W]hat Stevens saw in Germany was almost too much to absorb. He shot footage at Nordhausen, where the ravaged bodies of slave workers bore the grim evidence of starvation, torture, and murder. But Dachau was worse. There was nothing worse than Dachau. He shot boxcars packed with skeletal Jews; he shot ditches filled with the dead. He was in a world of indescribable horror. ‘We went to the woodpile outside the crematorium, and the woodpile was people.’ He filmed the extinct and the living. He filmed German officers and forced them to look at their handiwork, and he filmed German citizens, deniers all, in nearby villages, pretending they didn’t know what had been happening just down the road. He smelled the unbearable stench of the sick and the dying, and he saw signs of cannibalism among the heaped-up bodies.

“After seeing the camps,” he said, “I was an entirely different person.”

Stevens’ documentary films, including Nazi Concentration Camps, were entered as evidence in the 1945-46 Nuremberg Trials. When Stevens returned to Hollywood to make feature films, they were of a different order of seriousness. And these included the hard-hitting film based on Edna Ferber’s novel Giant.

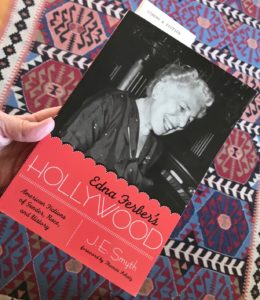

From J.M. Smith’s Edna Ferber’s Hollywood: American Fictions of Gender, Race and History:

“Stevens appreciated Ferber’s attack on Texas racism. He also shared Ferber’s commitment to creating unusual perspectives on the American past… His independent film company bought the rights in the summer of 1952, and then convinced Warmer Bros. to put up the money for the production and distribution… [Stevens’] desire to condemn racism and enshrine the old-style toughness of the western hero would result in a deeply conflicted western.” (pp.201-202)

*

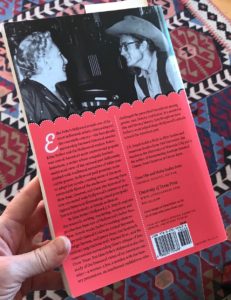

The back cover of J.E. Smth’s Edna Ferber’s Hollywood shows Jett Rink’s creators, writer and actor:

It was on location in Marfa that Ferber, who was old enough to be his grandmother, became friends with the brilliant young actor from Indiana. It must have seemed that Jimmy Dean had a long stretch of life before him, but in fact he was living out his last days. He would die in a car crash in California while Giant was still in production. In Ferber: Edna Ferber and Her Circle, Julie Gilbert quotes Edna, saying that, once home, she had received from Jimmy a photograph of him in character as Jett Rink:

It was not characteristic of him to send his photograph unasked. I was happy to have it and I wrote to thank him: “… when it arrived I was interested to notice for the first time how much your profile resembles that of John Barrymore. You’re too young ever to have seen him, I suppose. It really is startlingly similar. But then, your automobile racing will probably soon take care of that.”

I was told that the letter came the day of his death. He never saw it. (p.148)

In a uncanny way, Giant has become James Dean’s film, and the image of him sprawled in the back of the automobile, wearing his crown of a Stetson, gloves loosely, as if royally, grasped, cowboy boots up, that monstrosity of a Potemkin construction in the distance, the whole of it a talisman of the pump-jack power of American cool. Wrongly so perhaps, but Ferber and Stevens are no longer household names, but relegated to mentions in scholarly works and footnotes.

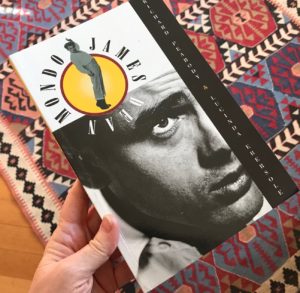

What is that magic eros that James Dean had, that for all these many decades he has managed to spark and hold the passionate interest of not only so many movie viewers, but other actors, and writers and poets? One could explore that question from a variety of disciplines for 500 years and forever, but here’s one illuminating and entertaining work, co-edited by my amigo, Richard Peabody: Mondo James Dean: A Collection of Stories and Poems About James Dean.

*

PS: TWO VIDEOS ON THE NUREMBERG TRIALS

The Nuremberg Trials were very present for me when I was a teenager, in part because World War II was then relatively recent— the older people in my life, including my parents, had all lived through that war, and I knew many people who had come to the US as refugees—or their parents had come as refugees. Moreover, my high school French and German teacher (she taught both languages) had served as a translator at the Nuremberg Trials.

So when I learned that George Stevens’ filming had played such an important role in the Nuremberg Trials, I went a ways into looking for videos around that issue. Here are two that I would warmly recommend watching.

Ashton Gleckman’s “I Am the Last Surviving Prosecutor of the Nuremberg Trials” The Story of Benjamin Ferencz:

Dr. Lee Merritt’s talk on Dr. Karl Brandt, who was condemned to death in the Nuremberg Trials. The story is complicated and important.

*

Look for my next Texas Books post on the first Monday of next month. You can find the archive of the Texas Books posts here.

You can also listen in any time to the 21 podcasts posted so far in my 24 podcast “Marfa Mondays” series exploring Far West Texas here.

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

Francisco I. Madero’s Commentary on the Baghavad-Gita (or Bhaghavad-Gita)

13 Trailers for Movies with Extra-Astral Texiness