This blog posts on Mondays.

In 2022 first Mondays of the month are for Texas Books, posts in which share with you some of the more unusual and interesting books in the Texas Bibliothek, that is, my working library.

> For the archive of all Texas-related posts click here.

P.S. Listen in any time to the related Marfa Mondays Podcasting Project.

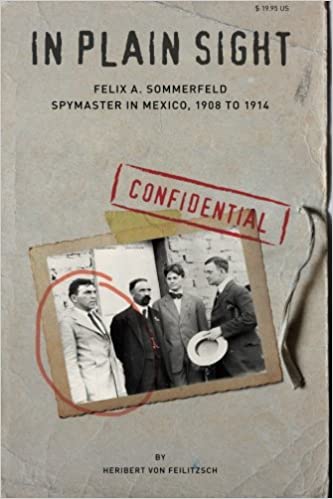

Texas shares its southern border with the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas, so of course “Texas Books” must include those about the US-Mexico border. Soldiers, spies, civilians, weapons, and supplies going back and forth across that border played a crucial role in many conflicts, most especially the Mexican Revolution. This Monday’s post is a review of Heribert von Feilitzsch’s In Plain Sight: Felix A Sommerfeld, Spymaster in Mexico, a work I consider one of the most astonishing, original, and important contributions in recent years to the history of that Revolution— which first battle, the Battle of Juárez, was watched from the rooftops of El Paso, Texas.

* * *

IN PLAIN SIGHT:

FELIX A. SOMMERFELD, SPYMASTER IN MEXICO, 1908-1914

by Heribert von Feilitzsch

Henselstone Verlag, 2012

Review by C.M. Mayo originally published in Literal Magazine, October 2016

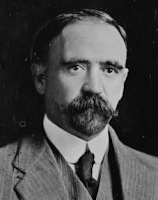

It was Mahatma Gandhi who said, “A small body of determined spirits fired by an unquenchable faith in their mission can alter the course of history.” Like Gandhi, Francisco I. Madero was deeply influenced by the Hindu scripture known as the Bhagavad-Gita and its concern with the metaphysics of faith and duty. And like Gandhi, Madero altered the course of history of his nation. From 1908, with his call for effective suffrage and no reelection, until his assasination in 1913, Madero received the support of not all, certainly, but many millions of Mexicans from all classes of society and all regions of the republic. But the fact is, during the 1910 Revolution, during Madero’s successful campaign for the presidency, and during Madero’s presidency, one of the members of that “small body of determined spirits,” who worked most closely with him was not Mexican. His name was Felix A. Sommerfeld and he was a German spy.

We must thank the distinguished historian of Mexico, Friedrich Katz, author of The Secret War in Mexico, among other works, for shining a bright if tenuous light on Felix Sommerfeld. Other historians of the Mexican Revolution have mentioned the mysterious Sommerfeld, notably Charles H. Harris III and Louis R. Sadler in their 2009 The Secret War in El Paso. But it is Heribert von Feilitzsch, by his extensive archival detective work in Germany, Mexico, and Washington DC, who has contributed our most complete—albeit still incomplete—understanding of who Sommerfeld was; Sommerfeld’s relationship with Madero; and his role, a vital one, in the Mexican Revolution.

Writes von Feilitzsch:

“No other foreigner wielded more influence and amassed more power in the Mexican Revolution. From head of security, Sommerfeld took on the development and leadership of Mexico’s Secret Service. Under his auspices, the largest foreign secret service organization ever to operate on U.S. soil evolved into a weapon that terrorized and decimated Madero’s enemies…”

While Sommerfeld was unable to prevent General Victoriano Huerta’s coup d’etat, and his warning to Madero escape arrest came too late, he himself escaped the capital. Continues von Feilitzsch:

“Sommerfeld became the lynchpin in the revolutionary supply chain. His organization along the border smuggled arms and ammunition to the troops in amounts never before thought possible, while his contacts at the highest eschelons of the American and German governments shut off credit and supplies for Huerta.”

Von Feilitzsch reveals that Sommerfeld was reporting not only to the German ambassador in Mexico City, Paul von Hintze, but from 1911 to 1914 to Sherburne G. Hopkins, lawyer and lobbyist par excellence in Washington. Hopkins had initially been brought on board for the cause by Madero’s brother and right-hand man, Gustavo Madero. To quote von Feilitzsch again:

“As a lawyer and lobbyist for industrialist Charles Ranlett Flint and oil tycoon Henry Clay Pierce, Hopkins enabled Sommerfeld to hold the entire keys for American businessmen trying to gain access to the Madero, Carranza, and Villa administrations.”

Sommerfeld was operating at the highest level of sophistication. And perhaps most telling of that sophistication is something surprisingly simple. It is a photograph of him taken in El Paso, Texas during the Revolution, the one that appears on the cover of von Feilitzsch’s book.

In a light-colored suit and dark tie, Sommerfeld stands at Madero’s elbow, protecting his back. On Madero’s opposite side journalists Allie Martin and Chris Haggerty crowd close, seemingly mesmerized by the glamorous revolutionary. Haggerty holds the brim of his hat, pale circle, as if he had only just swept it from his head. But on the other side, just slightly behind Madero, Sommerfeld, bareheaded, craggy-faced, with eyes that belong to an eagle, looks out— a secret service man’s gaze. It is an iconic photograph; those who study the Mexican Revolution will have seen it.

The telling thing, though, is this: that in the archive which has the original, the Aultman Collection in the El Paso Public Library, Sommerfeld, the man with the eagle-gaze, that man who so often appears right by Madero’s side, and here and there in other iconic photographs of the time, including one of the guests at the dinner with Madero and family to celebrate the Battle of Juárez, is unidentified. Or at least he was unidentified there at the time von Feilitzsch wrote his book. In short, during the Revolution, and for over a century to follow, Felix Sommerfeld had been hiding in plain sight. In Plain Sight: the title of von Feilitzsch’s book.

AN ESOTERIC CONNECTION?

I am more grateful than I can say to have encountered In Plain Sight when I did, and I believe that anyone who studies the Mexican Revolution, after reading this book, will say the same. The Mexican Revolution has thousands of facets, of course, but for my own work, the key questions were, Who was Francisco I. Madero? How, in the nitty-gritty, did he pull it off, to lead a Revolution and win the presidency? And, in the face of inevitable and ferocious counter-revolution, how did Madero manage to hold the presidency for as long as he did?

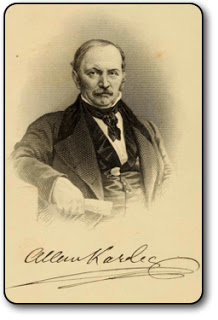

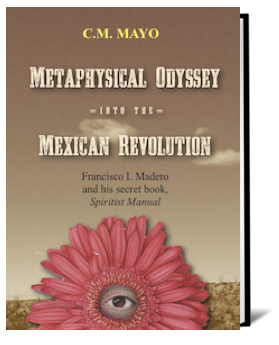

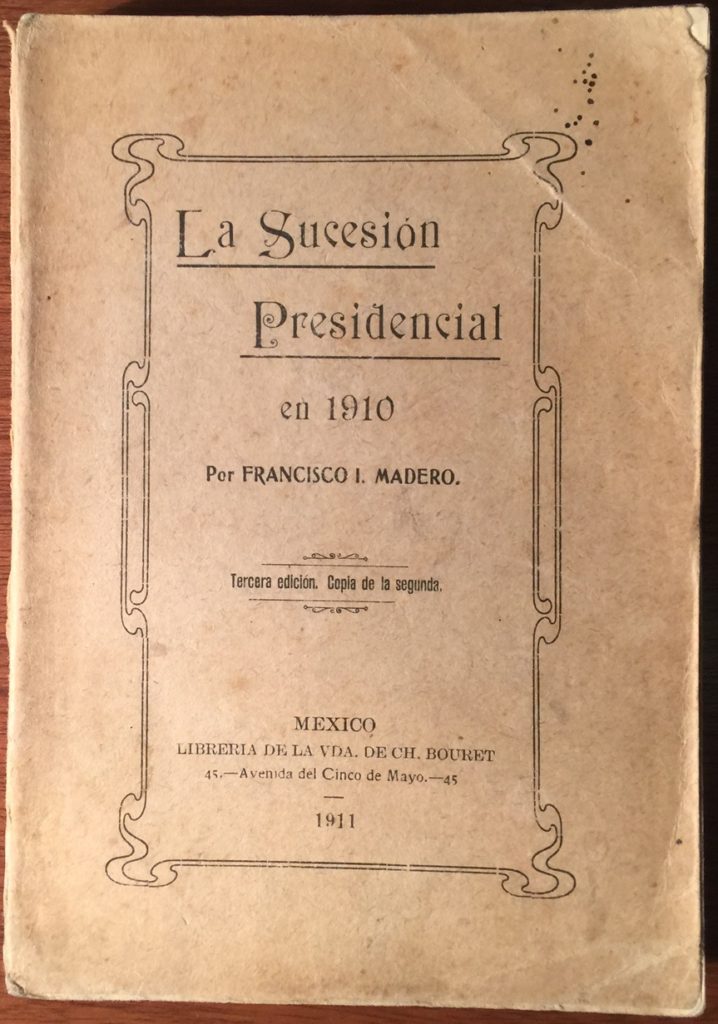

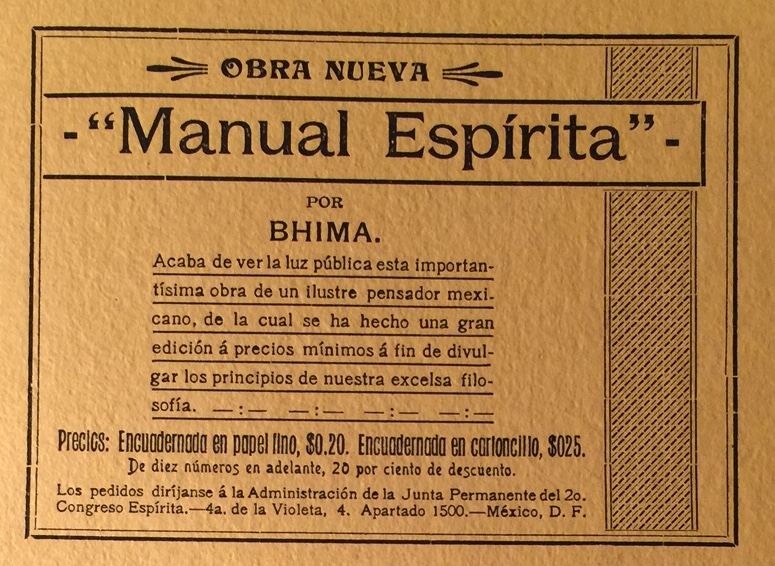

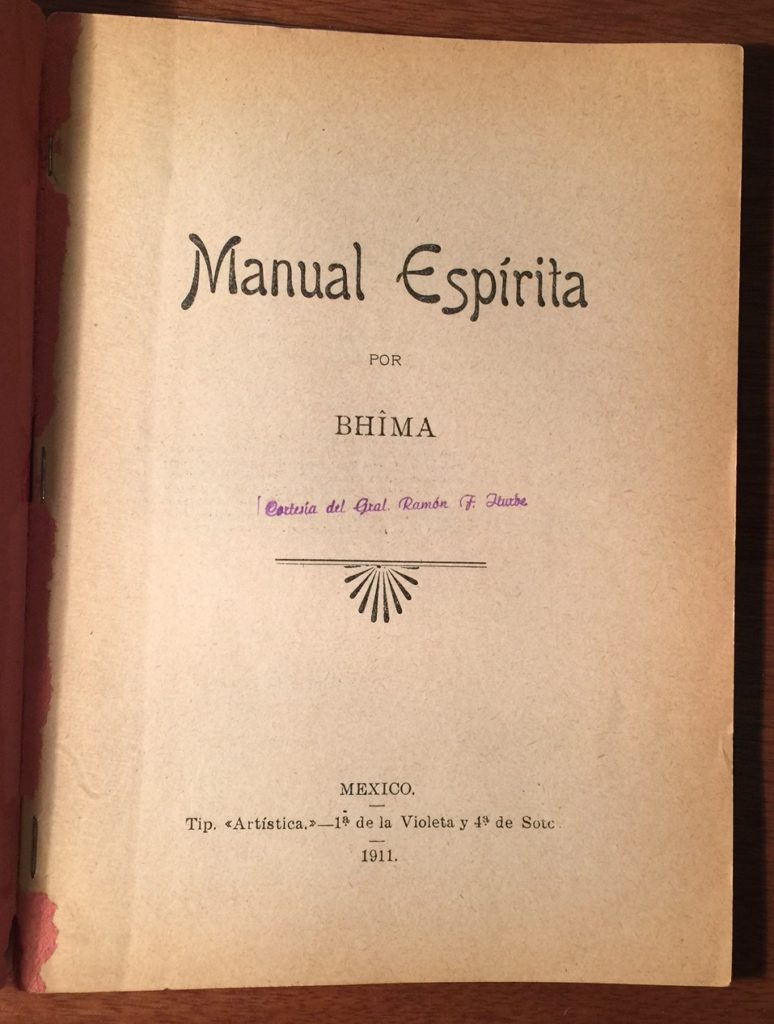

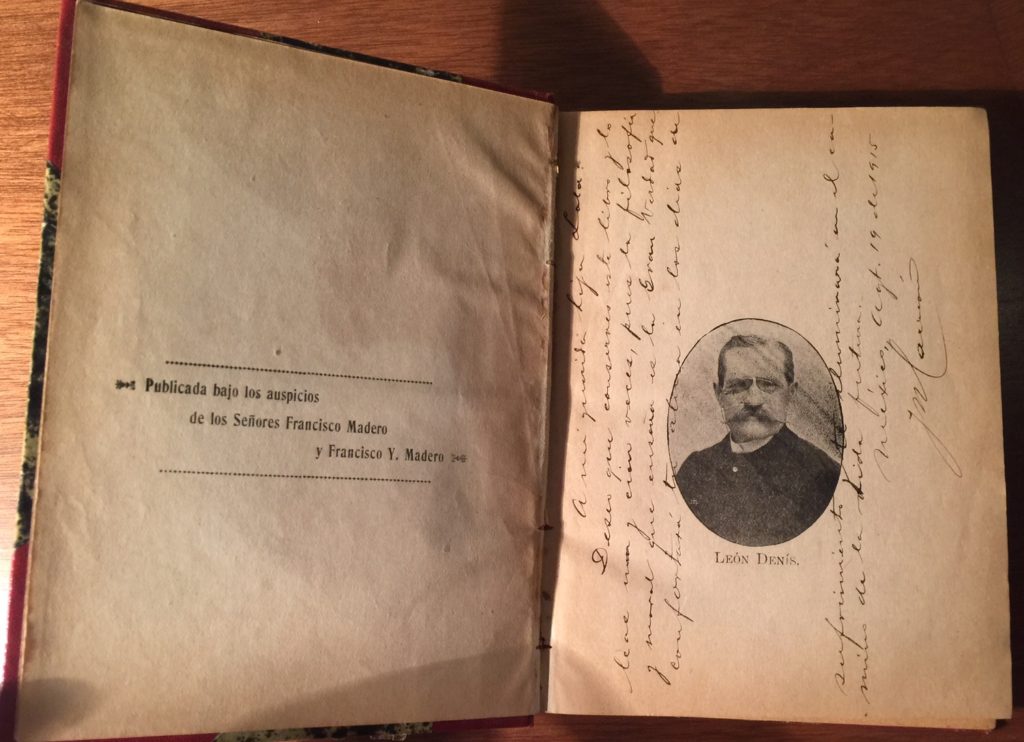

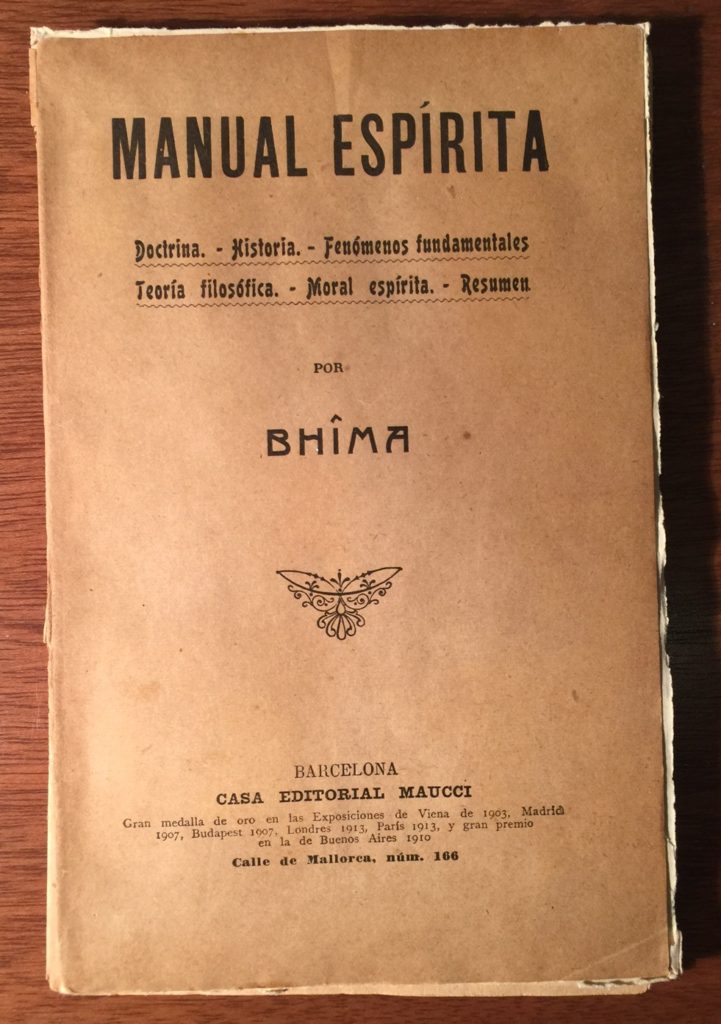

My work, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution, was prompted by my encounter with Madero’s secret book, Manual espírita (Spiritist Manual). A blend of Kardecian Spiritism, Hindu and other esoteric philosophies, Manual espírita was published in 1911 under the pseudonym “Bhima.”

Never mind what was in Manual espírita, this slender volume with now yellowed pages: the fact that Francisco I. Madero, leader of the 1910 Revolution, had written it and moreoever, published it when he was president-elect in 1911— I could not but conclude that its contents must been exceedingly important to him, and hence, offer profound understanding into who he was and what he stood for.

But my intention here is not to talk about my book about Madero. I suffice to mention that, apart from benefitting so much from the information and insights in von Feilitzsch’s book, I took the liberty of emailing von Feilitzsch a question: What kind of person was this Sommerfeld—might he have been a Spiritist? For there was another German spy working closely with Madero, a Spiritist who turns out to have become a major figure in esoteric circles in the first half of the 20th century: Dr. Arnoldo Krumm-Heller.

Von Feilitzsch was kind enough to permit me to include his answer in my book. He writes:

“With respect to Madero’s Spiritism, Sommerfeld not only knew all about it. I am convinced that he was a kindred soul. I have scoured the earth for a book Sommerfeld wrote around 1918, likely under a pen name. I cannot find it. This might be the only possible source for a glimpse into this man’s deepest convictions and emotional structure. Sommerfeld became so close to Madero at the exact time, when Madero must have been under the most emotional pressure. Madero hated bloodshed and violence and exactly that he set off when the revolution started. In his innermost circle were Sommerfeld, [Arnoldo] Krumm-Heller, his wife Sara, and Gustavo, which is documented. … (Sommerfeld was [Sara’s] bodyguard in Mexico City and the last address I have for Sommerfeld reads: c/o Sara Madero, Mexico City. This was in 1930). Just like…Madero, Sommerfeld did not drink, gamble or smoke. In that time and considering the background of Sommerfeld as a mining engineer in the “Wild West,” this is a very unlikely coincidence. In his interviews with the American authorities, he said that Madero was “the purest man I ever met in my life. When I spoke to him, he took my breath away—the child’s faith of this man in humanity.” (Justice 9-16-12) In his appearance before the Fall Committee [of the US Senate] in 1912 he testified: “President Madero is the best friend I have in this world…” Senator Smith “…you became interested in him?” Sommerfeld: “Yes, we became very close friends.” And so on. I definitely hear undertones of esoteric connection. Sommerfeld was very private, rarely allowed a picture taken, and certainly never talked about his faith or personal life to anyone. As someone very rational he kept his distance to others and never described any other relationship in these highly emotional terms. Until I can put my hands on his personal papers or his book, these are only indications but still worth thinking about.”

MORE THAN WE MIGHT HAVE DARED HOPE FOR

In many ways Felix Sommerfeld remains a mystery. Von Feilitzsch however, has given us much more than we might have dared hope for: That Felix Sommerfeld was born on May 28, 1879 near Schniedemühl, then in Prussia. As owners of a grain mill, his family was relatively wealthy. Like many Germans in the late 19th century, he had relatives, including brothers, who emmigrated to the United States. As a teenager Felix lived with his brothers for a time in New York. He joined the US Army and received training in Kentucky—then went AWOL, back to Germany. In the first years of the 20th century von Feilitzsch finds Felix Sommerfeld serving in the Prussian cavalry in China during the Boxer Rebellion. Then, he pops up as a mining engineer in Arizona and then northern Mexico—perhaps by then already reporting to the German consul in Chihuahua. Then he’s back to Germany, then, back again in Mexico as a journalist—and all of a sudden, in charge of revolutionary leader Francisco I. Madero’s secret service.

One more of so many things von Feilitzsch brings to us about Felix Sommerfeld: He was Jewish. We do not know his fate, but if he lived into his sixties he may have perished in the Holocaust—or perhaps he disappeared, as secret agents know how to do.

In the Bhagavad Gita, which we know that Francisco Madero read and reread, penciling copious notes in the margins, Lord Kirshna, incarnation of cosmic power, advises the warrior Arjuna to have heart, to do his duty. For Madero, that meant putting aside material concerns and gathering around himself that “small body of determined spirits,” who would help him to alter the course of Mexico’s history. As Madero understood it, those “spirits” would have been both disincarnate and incarnate. Whether and to what degree his chief of secret service shared Madero’s esoteric inclinations remains an open question. But in revealing that, both during and beyond Madero’s lifetime, Felix Sommerfeld was an indispensible member of that “small body,” von Feilitzsch has made a contribution to the history of the Mexican Revolution that is at once disquieting and sensational.

*

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

Synge’s The Aran Islands and Kapuscinski’s Travels with Herodotus