This blog posts on Mondays. This year, 2021, I am dedicating the first Monday of the month to Texas Books, in which I share with you some of the more unusual and interesting books in the Texas Bibliothek, that is, my working library. Listen in any time to the related podcast series.

Photo: C.M. Mayo.

With time and patience and, presumably, approved government-issued identification and a credit card, you can easily drive or fly across Far West Texas. But just look out the window at this rough, bone-dry country and you’ll know, your path across it would be nigh impossible without fossil fuels.

For many thousands of years, as archaeological evidence attests, people came into its spring-laced mountains, and also camped in its ciénegas (oases), such as Hueco Tanks, for seasonal hunting and fishing, and processing that meat, and seeds, berries, and roots. When out hunting or moving on, they would follow the big river we call the Rio Grande or a creek, such as Toyah or Alamito— or if not, they would would have known, whether by direct knowledge or tradition, how far they would have had to walk until the next source of water, and how to find it. To extend their range, they wore sandals woven of lechugilla, and used gourds and baskets to carry food and water. In hot weather they would have walked by moonlight. But no one in their right mind would have set out walking for hundreds of miles over the open desert, on so straight and water-scarce a path as our asphalted highways.

The transportation technologies that harnessed the horse, mule, burro and donkey arrived in the Americas with the European colonists in the 16th century. For this form of transportation, fuel is forage. And you need water. You either have enough forage and water, and at regular intervals, or the animals collapse and die. You also need to give them a chance to rest.

Flash forward to 1858. The American Southwest, including gold-rich California, is the prize of the US-Mexican War, which had concluded a decade earlier. Texas, having revolted and won its independence from Mexico in 1836, had become the 28th state of the Union in 1845. The unfathomably vast deposits of petroleum and natural gas lie deep within in its Permian Basin, a complex of geologic structures and sub-basins named after the Permian Period of 299 to 251 million years ago. Part of the Permian Basin extends into Far West Texas, that is, Texas west of the Pecos River, the subject of my book in-progress. But in 1858 no one imagined that fabulous abundance of “black gold,” nor could they have dreamed of the material and, consequently, political power it would allow the United States to command over the world over so much of the twentieth century. The Permian Basin wasn’t even a concept in 1858. No one then saw anything much of value in Far West Texas, except some salt. As for the Pecos, as one old-timer told historian Patrick Dearen, it was so brackish “a snake wouldn’t drink it.”

Texas west of the Pecos was a brutal inconvenience to be crossed, as quickly and cheaply as possible, either on the way to, or the way back from California. In addition to the lack of water, there was the ever-present danger of attacks by bandits, and by Apaches, Comanches, and Kiowa. Fossil-fuel-powered transport—the railroad— was coming to Far West Texas, but the track would not be hammered into place until many years after the US Civil War, which outbreak lay three more years over the horizon. In 1858, for these parts, the cutting-edge transportation technology was the stagecoach: a wheeled box for mail and passengers, hauled over dirt roads by a team of mules or horses. The idea was, at the scheduled stops on its route, passengers could get on and off, have a rest and a bite to eat, the mailbags could be unloaded and loaded, and the animals refreshed.

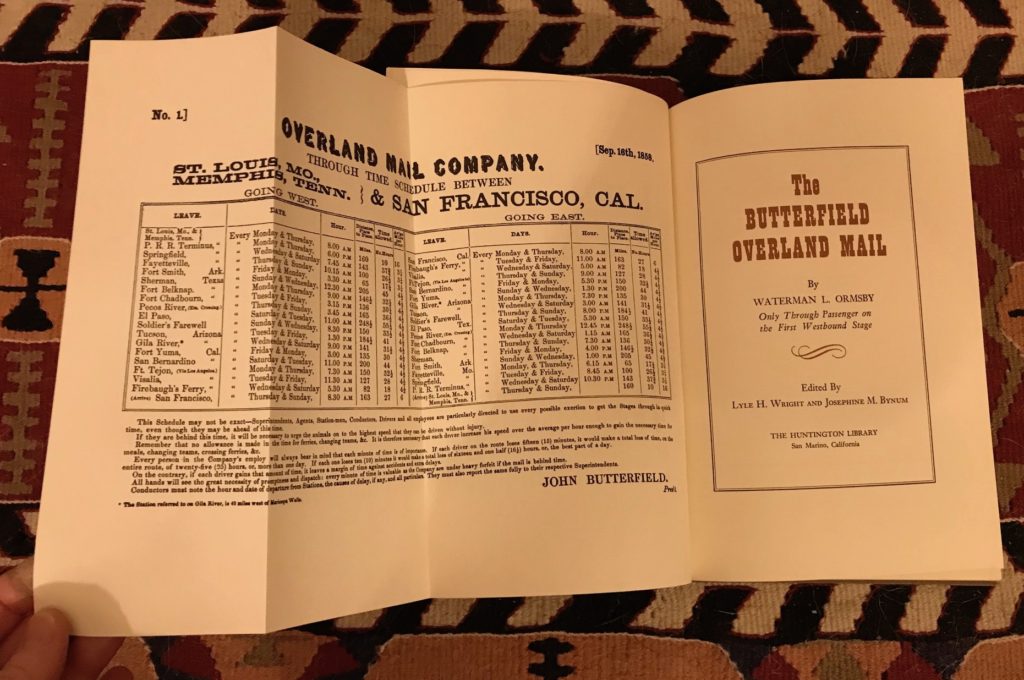

In 1857, an act of Congress had authorized a mail and passenger stage line to connect St Louis / Memphis and San Francisco. The Postmaster General selected the route that swi=ung down into Far West Texas (among the many considered), and awarded the contract for the semi-weekly service to John Butterfield and associates. At 2,700 miles long, Butterfield’s Overland Mail would be not only the longest stagecoach line in the world, but a chapter, albeit brief—it ended with the outbreak of the Civil War— of signal importance in the economic development and cohesion of the United States.

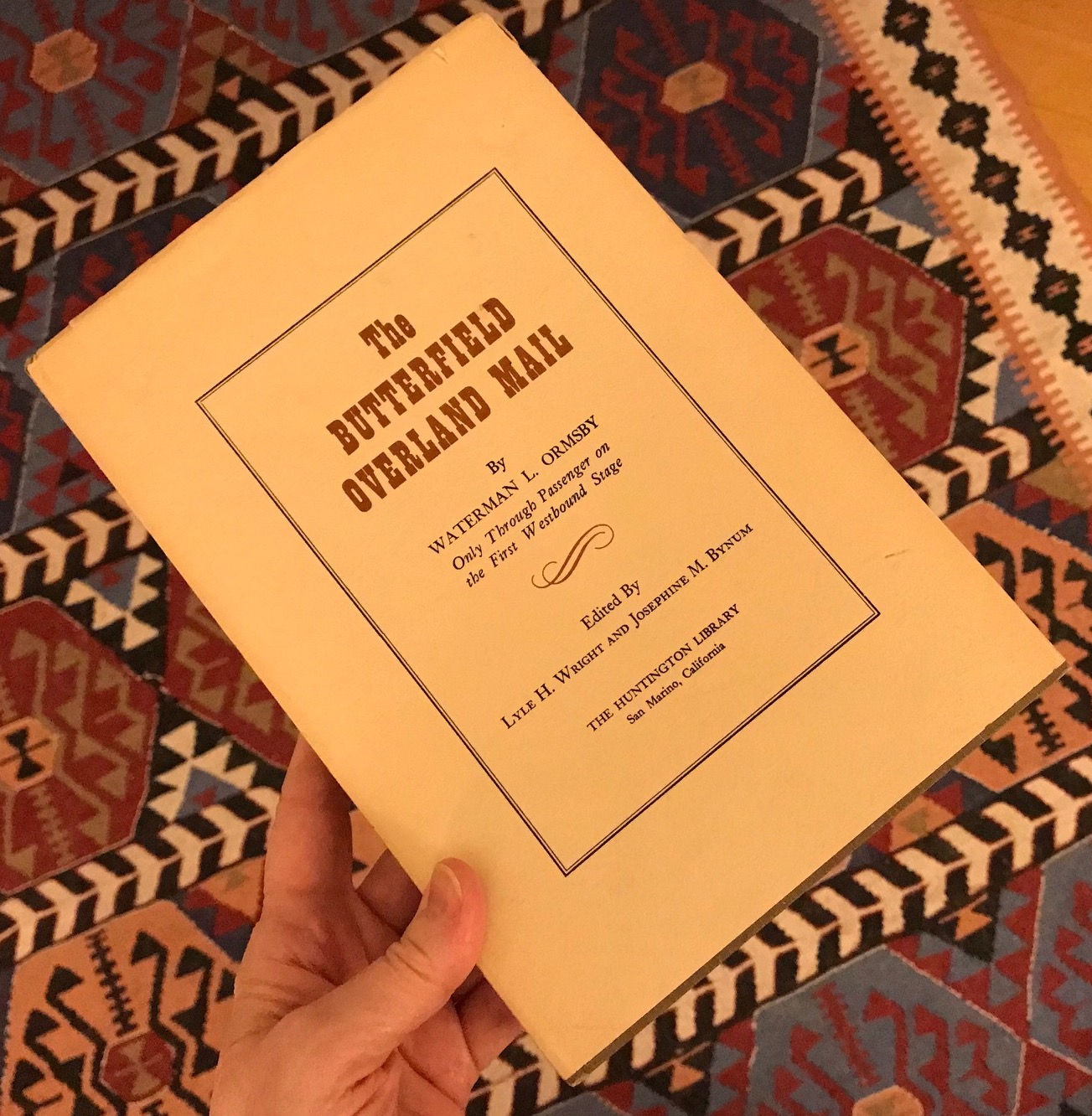

The first through-passenger on the west-bound stage was Waterman L. Ormsby, a 23 year-old New Yorker, whose eight reports appeared in the New York Herald.

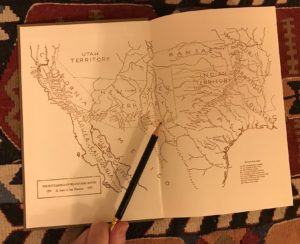

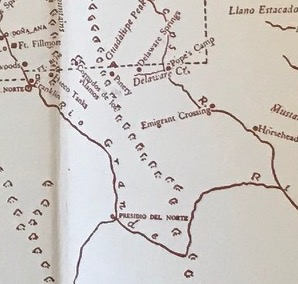

The map from the book (above), shows the stagecoach stops for the Butterfield Overland Mail Route, from St. Louis (at the far top right, east) to San Francisco (far top left, west). That map is difficult to make out, I’ll grant. The map below is a close-up of Trans-Pecos Texas, from the same map. The Butterfield Overland arrived at the Pecos River at Horsehead Crossing, then traveled up alongside its the steep banks to Emigrant Crossing, and then on up the Pecos to Pope’s Camp. Then, heading west, the stage stopped at Delaware Springs; the Pinery, in the shadow of Guadalupe Peak (now the Guadalupe Mountains National Park); Cornudas by the salt beds; the oasis of Hueco Tanks; and finally, the tiny settlement of Franklin, now known as the city of El Paso—before heading to parts further west.

The schedule shows that the stagecoach departed the Pecos River (Emigrant’s Crossing) on Thursdays and Sundays at 3:45 AM, averaging 4 1/2 miles an hour, to arrive at El Paso Saturdays and Tuesdays. The footnote reads, in part: “If they are behind this time, it will be necessary to urge the animals on to the highest speed that they can be driven without injury.”

The pressure to profit in the capitalist race against the clock comes through vividly in Ormsby’s reports. From his report near El Paso, Texas, September 28, 1858:

“We travel night and day, and only stop long enough to change teams and eat. The stations are not all yet finished, and there are some very long drives—varying from thirty-five to seventy-five miles—without an opportunity of procuring fresh teams.”

Ormsby’s report for the New York Herald of October 10, 1858, from San Francisco, is the one that details the crossing of Far West Texas. He begins:

“Safe and sound from all the threatened dangers of Indians, tropic suns, rattlesnakes, mustang horses, jerked beef, terrific mountain passes, fording rivers, and all the concomitants which envy, pedantry, and ignorance had predicted for all passengers by the overland mail route over which I have just passed, here I am in San Francisco, having made the passage from the St. Louis post office to the San Francisco post office in twenty-three days, twenty-three hours and a half, just one day and a half an hour less than the time required by the Overland Mail Company’s contract with the Post Office Department.”

(It is only the fact that he was a 23 year old New Yorker that inclines me to believe him, a little, when he claims, “I feel almost fresh enough to undertake it again.”)

Arriving at the Pecos River, which had “no trees or any unusual luxuriance of foliage on the banks,” the driver who takes charge of the stagecoach is:

“Captain Skillman, an old frontier man who was the first to run the San Antonio and Santa Fé mail at a time when a fight with the Indians, every trip, was considered in the contract. He is a man about forty-five years of age, in appearance much resembling the portraits of the Wandering Jew, with the exception that he carries several revolvers and bowie knives, dresses in buckskin, and has a sandy head of hair and beard. He loved hard work and adventures, and hates ‘injuns,’ and knows the country here pretty well.” (p.68)

But it wasn’t all Kumbaya and PETA for the mules:

“We started with four mules to the wagon and eighteen in the cavellado; but the latter dwindled down in number as one by one the animals gave out.” (p.69)

The stagecoach jolted up alongside the north shore of the Pecos for sixteen miles, then:

“met a train of wagons belonging to Mr. McHenry, who was going from San Francisco to San Antonio, carrying a load of grain for the company on the way. By his invitation, we stopped and breakfasted with him, giving our mules a chance to eat, drink and rest—all of which they much needed.”

Miles later, after Emigrant Crossing, and another slogging day:

“We continued our weary and dusty road up the Pecos…inhaling constant clouds of dust and jolting along almost at snail’s pace. Our animals kept giving out so that we had to leave them on the road; and by the time we reached Pope’s Camp at least half a dozen had been disposed of in this way. ” (p.71)

But, O, Nature!

“As we neared Pope’s Camp, in the bright moonlight, we could see the Guadalupe Mountains, sixty miles distant on the other side of the river, stranding out in bold relief against the clear sky, like the walls of some ancient fortress covered with towers and embattlements. I am told that on a clear day this peak has been seen across the plains for the distance of over one hundred miles, so tall is it and so low the country about it.” (p.71)

At Pope’s Camp, they got their fresh team—and “some supper of shortcake, coffee, dried beef and raw onions” (p.72) that beef being cooked over a fire of buffalo chips (yes, that is what you think it is).

Ormsby continues:

“The Guadalupe Peak loomed up before us all day in the most aggravating manner. It fairly seemed to be further off the more we traveled, so that I almost gave up in despair all hopes of reaching it. Our last eight or ten miles were among the foothills of the range, and I now confidently believed we were within a mile or two, at the outside. But the road wound and crooked over the interminable hills for miles yet and we seemed to be no nearer than before. I could see the outlines of the mountain plainly, and as I eagerly asked how far it was, the captain laughingly told me it was just five miles yet, and we had better stop to give the animals a little rest or they could never finish it. ” (p.73)

So stop they did, by the cool, bubbling water of Independence Spring. Then:

“We were obliged to actually beat our mules with rocks to make them go the remaining five miles to the station” (p.73)

*

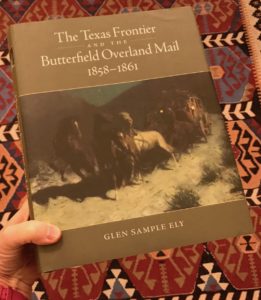

For a complete and splendidly illustrated history of the Overland Mail, nothing to date beats Glen Sample Ely’s The Texas Frontier and the Butterfield Overland Mail 1858-1861 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2016). I am fortunate to have a copy of this magnificent tome in my working library.

About those stagecoaches and their teams, writes Ely:

“The stagecoaches used by the Overland Mail Company in West Texas were not the heavy wooden Concord coaches seen in such popular Western movies as Stagecoach. Along the arid frontier, it was too taxing on livestock to pull a cumbersome Concord through deep sand roads in dry weather or through boggy stretches after heavy rains and flooding. In Texas, the typical passenger vehicle was the lighter, canvas-topped Celerity wagon, also known as a mud wagon.” (p.15)

As for the mules:

“Much of the time, four-mule teams were hitched to Butterfield’s mud wagons, although horses were used on some sections of the route. The livestock varied in cost: the lead mules at the front of the team ran $35 to $40 each, whereas higher-grade mules (known as “wheelers”) costing $70 to $80 each were used at the back of the team, closer to the coach. The Overland Mail Company kept ten to twenty mules on hand at each station. Butterfield’s larger regional depots kept fifty to sixty animals in reserve for needed adjustments along the line.” (pp.15-16)

To keep them in feed was a challenge:

The Overland Mail Company kept a large supply of corn and hay on hand for the livestock, as the local terrain was usually too sparse to support a station’s requirements year-round. Local grasses were most prevalent from spring to early fall, during the so-called rainy season. Leaving the stage stop to go out and cut hay was often a deadly task. Raiding Comanches and Apaches targeted employees out on forage detail.” (p.17)

It was reported that, even for 50 dollars an hour—a stupendous sum at the time—there were occasions when no man would cut hay. Speaking of which, on next month’s first Monday I’ll be showcasing some of the captivity memoirs in my working library.

*

Look for my next Texas Books post on the first Monday of next month. You can find the archive of the Texas Books posts here.

You can also listen in any time to the 21 podcasts posted so far in my 24 podcast “Marfa Mondays” series exploring Far West Texas here.

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

From the Texas Bibliothek: The Sanderson Flood of 1965;

Faded Rimrock Memories; Terrell County, Texas: Its Past, Its People

A Review of Patrick Dearen’s Bitter Waters

The Power of Literary Travel Memoir: Further Notes on

David M. Wrobel’s Global West, American Frontier