This blog posts on Mondays.

In 2022 first Mondays of the month are for Texas Books, posts in which share with you some of the more unusual and interesting books in the Texas Bibliothek, that is, my working library.

> For the archive of all Texas-related posts click here.

P.S. Listen in any time to the related Marfa Mondays Podcasting Project.

“I believe that if you make a film properly today, it’ll be watched by people in fifty years time”—George Stevens

Last month I devoted the first-Monday-of-the-month “Texas Books” post to several works related to the iconic movie Giant, which was based on Edna Ferber’s best-selling and Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. It’s nigh impossible to exaggerate the influence of that 1956 movie on shaping popular concepts and imagery of Far West Texas—although, strange to say, neither the author of the novel it was based on, nor the starring actors, nor the director of Giant were Texan. George Stevens (1904-1975), who won an Academy Award for Best Director for Giant, was a liberal Californian through-and-through. But unlike most of his fellow Hollywood directors, Stevens volunteered to serve in World War II, in which for a mobile film unit he documented, among other events and places, the liberation of Dachau. Two of the films he directed, The Nazi Plan (1945) and Nazi Concentration Camps (1945) were screened as evidence in the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials.

Stevens, who got his start filming Laurel and Hardy comedies, and later directed such stars as Katherine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, was to become one of Hollywood’s first major producer/ directors. However, his directing career was cleaved by World War II. Prior to the war, he made myriad light comedies and entertainments; afterwards, the serious and meticulously researched dramas, including Shane, the epic Giant, and The Diary of Anne Frank. As Stevens told one interviewer, “After seeing the camps I was an entirely different person.”

So who was this person, this Hollywood Californian, who had become another person whose vision of Texas in the mid-1950s has had such a powerfully lasting influence?

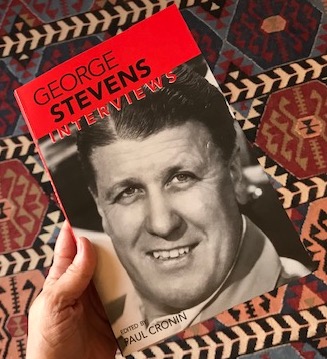

After last month’s “Texas Books” post on Giant I realized I needed to learn more about its director; specifically, to better see Giant in the context of his oeuvre. So— abebooks.com to the rescue—I put in an order for the now out-of-print collection of interviews edited by filmmaker and film historian Paul Cronin, George Stevens Interviews (University Press of Mississippi Press, 2004).

I devoured the editor’s excellent introduction, chronology and filmography, and all the interviews from 1935 to 1974— spanning nearly four decades.

A few quotes that stood out for me:

From the interview given to William Kirschner, Jewish War Veterans Review, August 1963:

[On the liberation of Dachau] “It was unbelievable. What is there to say about such enormities and abuse. A fellow in my unit who was something of a linguist wrote letters for the dying to their relatives without interruption for days and nights at a time. It was like wandering around in one of Dante’s infernal visions. (pp.18-19)

“Nothing has disturbed me in my life as much as the Hitler outrages. It’s the reason I got into the war, and I finally wound up in a concentration camp on the day it was liberated. I hated the German army. What they stood for was the worst possible thing that’s happened in centuries.” (p.21)

[On the wartime experience] “It was an elaborate change in my life… Professionally, I knew I wanted to do very different things to what I’d done before. In this respect, the film that was very important to me was The Diary of Anne Frank.” (p.21)

[On films in general] “The business of people gathered together in great numbers to look at a screen and agree or disagree upon ideas as acted out in front of them, I think it’s one of the great adventures of our time.” (p.23)

From the interview given to James Silke, Cinema, December-January 1964-65:

[On films in general] “I think all people are very curious about experiences, experiences that in this little life span they may not experience for themselves. A film is a remarkable way for people to experience things they would not have had the opportunity to experience in any other way. And I think the best in films occurs when they bring the response, ‘That’s it!'” (p.48)

From the interview given to Robert Hughes, 1967:

“This is what the theater does so well. People gathered in a large group, finding a little something about themselves. When the audience was truly moved, it was absolutely quiet. They were in communion because they were learning the truth about themselves. They were there for discivery, not entertainment. They say film is a narcotic, an escape. But when film was done right, it asked real questions: Who am I? Why am I? Why do I do this? Real theater and film is therapy for the audience.” (p.60)

[On Dachau] “After seeing the camps I was an entirely different person. I know there is brutality in war, and the SS were lousy bastards, but the destruction of people like this was beyond comprehension. This is where I really learned about life… We went to the woodpile outside the crematorium, and the woodpile was people. I remember there was a whole area for Yugoslavs. The only reason I knew they were Yugoslavs was because they had a tag on their coats or a broad purple crayon mark on their chests. There was a dissecting thing in the crematorium where they cut people apart before they put them in there.”(p.65)

From the interview given to Bruce Petri, 1973

(reprinted from A Theory of American Film: The Films and Techniques of George Stevens, Garland Publishing, 1987)

“So I keep the camera back in a position that is not going to help the audience too much…We’re curious creatures, and we like to discover for ourselves. In the world that we’re living in, in the film, the film is exposing life to you for your convenience. It must, to a degree, and it can under many situations without resentment; but I think it’s an enormous waste not to give the audience its priority of discovery, as much as you can.” (p.90)

From the interview for the American Film Institute, 1973:

[On Giant] “The structural development of the picture, I believe, is what saves it. It has an excellent structure design, which has to do with the audience anticipating and looking some distance ahead all the way to the finish, which is a reversal on how this kind of story would normally end— the hero is heroic. Here the hero is beaten, but his gal likes him. It’s the first time she’s ever really respected him because he’s developed a kind of humility— not instinctive, but beaten into him.” (p.102)

[On film in general] “It’s all about making sure the film bounces off that sheet and comes to life in the mind of the audience. What is a film outside the audience’s mind?” (p.104)

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

Into the Guadalupe Mountains:

Some Favorites from the Texas Bibliothek

(Plus a Couple of Extra-Crunchy Videos)

The Marfa Mondays Podcast is Back! No. 21:

“Great Power in One: Miss Charles Emily Wilson”

Lord Kingsborough’s Antiquities of Mexico