This blog posts on Mondays.

Second Mondays of the month I devote to my writing workshop students and anyone else interested in creative writing. Welcome!

> For the archive of workshop posts click here.

A few years ago I gave a talk for the Women Writing the West conference, “On Seeing as an Artist: Five Techniques for a Journey Towards Einfühlung.” I recently reread it and, rare for me to say, I wouldn’t change a word (although I did fix a typo). Of late, I’ve had some conversations on this very subject, so I thought I’d take it up again for this second Monday of the month’s writing workshop post.

If you’re ever flummoxed for something to write about, a rich source of narratives you can do endless permutations upon are fables and fairytales. Something is at stake, characters are at odds— go to it! Make the fox who doesn’t want sour grapes, say, a stockbroker who doesn’t want that condo in Aspen. Make the princess and the pea a university student who tweets about her upset with outrageously insensitive professors. Rename the tortoise Ludovika and make her a STEM major; the hare, that’s her cuz, Jimmy the Adderall-addicted skateboarder. And so on.

Speaking of seeing, one of my personal favorites among that vast corpus of European fables and fairytales is Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Emperor Has No Clothes” (sometimes translated as “The Emperor’s New Clothes”). Dear writerly reader, I am confident that you are already familiar with that story, so I won’t recount it here, but if you need a refresher or if you grew up in, say, the highlands of Papua New Guinea, here is an English translation. (And if you did grow up in the highlands of Papua Guinea I sincerely ask you to tell me the equivalent fable from your culture; I have no doubt that you have one!)

As I often take pains to point out in my workshops, reading as a writer is a very different endeavor than reading for entertainment or for scholarly purposes. Of course most people would come across “The Emperor’s New Clothes” in a children’s book, and read it for entertainment. The hero of the story is the little child who cries out: “But the emperor has nothing on at all!” Most readers are most entertained when they can identify with the hero. What’s to identify with? His shining innocence, his honesty, his courage in speaking truth to power. We can be sure, he’s as cute as Jackie Coogan, too.

As for that foolish emperor and his hypocritical courtiers, we give them the big, fat, farty raspberry!

What I would suggest to you, dear writerly reader, is that the more interesting characters in this fairytale, and that are worthy of exploration and fleshing out in literary fiction, are the emperor and his courtiers. What might they think and what might they say after the child, in his innocence, has broken the spell?

We know from the story what the emperor thinks and feels in that moment—he knows that the child is right, he recognizes that the crowd of his subjects agrees with the child, but he, in his underwear, and his courtiers, their hands in the air “holding” his imaginary train, continue the procession more seriously than ever.

But what about that night? The next day? A week later? A decade later?

At the end of their lives?

Use your imagination to go to those points, and tell us how, concretely, the life of the emperor and his courtiers lives have been upturned— or not? With whom are they now allied / upon whom do they now depend ? And what it is that, a day later, a week later, a decade later, or on the last day of their lives, they deny, although it is plainly before them? Describe the state of their self-images, and of their souls. You might use imagery, specific detail that appeals to the senses, dialogue, action.

For symphonic effect, tell about, say, their relationships with their dogs. Or, dogs in general. Do they prefer beagles? Or German shepherds? And so on.

*

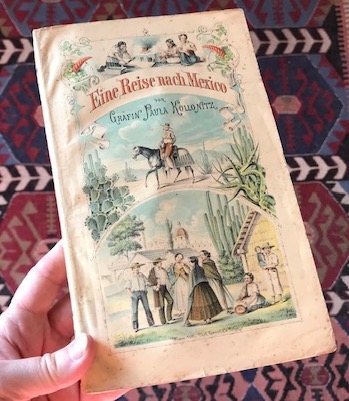

Speaking of emperors, courtiers and clear seeing, a few months ago I began a side project of translating Eine Reise Nach Mexico, a German language memoir by Countess Paula Kollonitz, an Austrian lady-in-waiting who traveled to Mexico as part of Maximilian and Carlota’s entourage in 1864. (It is a memoir I originally read in Spanish translation, and I made use of many of the details she recounts in my historical novel, The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire. For those unfamiliar with the history of Mexico’s Second Empire, I warmly recommend my podcast interview with M.M. McAllen, author of the superb narrative history, Maximilian and Carlota: Europe’s Last Empire in Mexico.) You can read Eine Reise Nach Mexico now for free in the original (if you can handle Gothic font) and in a 19th century English translation on archive.org. My purpose, apart from a more modern English translation, is to provide an introduction and notes.

by Paula Kollonitz

Countess Kollonitz writes about her journey some two years afterwards, when it was obvious to even the most deluded adherents that Maximilian von Habsburg’s Mexican adventure was doomed. It makes for uncanny reading— and it’s interesting to note what she, a lady-in-waiting from the Hofburg, dares to say, and what she doesn’t say, but that would have been obvious to her either at the moment she chronicles, or later, as she was writing. Eine Reise Nach Mexico was published in Vienna in May of 1867, the month before Maximilian’s execution in Querétaro. It so happens that I saw the elaborately pleated shirt Maximilian wore for that occasion, on display in a museum in Mexico City. It was pierced by several bullet holes and stained with blood.

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

From the Archives:

Sam Quinones’ Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic

One Simple Yet Powerful Practice in Reading as a Writer