This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

I was delighted to get the announcement for Sleight Work from W. Nick Hill, a poet and translator I have long admired. Sleight Work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 3.0 License. The author invites you to download the free PDF from his website and have a read right now!

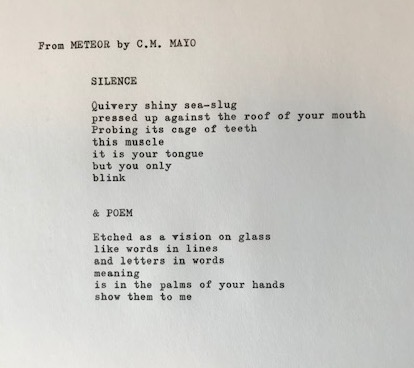

Here is one of the poems from W. Nick Hill’s Sleight Work which seems to me the very spirit of the book:

NOTICE

by W. Nick Hill

I live in a desert at the mouth of a mine.

The rocks and geodes I leave out on the sand.

If something fits your hand

Go ahead with it.

Here is his bio as it appears in Sleight Work:

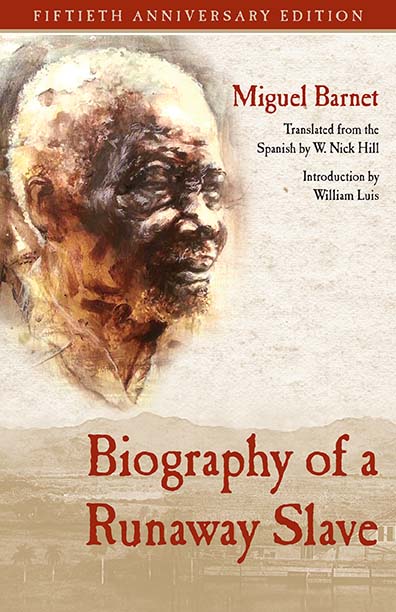

Walter Nickerson Hill was born in Chicago, raised in São Paulo, Brazil, and has spent lots of time in Oaxaca, Mexico. He shared Latin American culture with U.S. college students for a long time. Author of numerous academic reviews and articles, he has also translated the work of noted Latin American novelists and poets including Alvaro Mutis, David Huerta, and Miguel Barnet: Biography of a Runaway Slave. His English versions of poems by Mexican Jorge Fernández Granados’ Principle of Uncertainty, appeared as Constructed on Coincidence (Mid-American Review 2010). He is currently translating Gary Lemons’ Día De Los Muertos into Spanish. Hill has one slim award for a chapbook and will have three collections of poetry after Sleight Work comes out in November 2018. He lives on the Olympic Peninsula with his wife. Visit http://wnickhill.net

Before we delve into the Q & A, another favorite from Sleight Work:

After Hyde’s The Gift

by W. Nick Hill

Breathe it in and with your panorama lit up just now to the scope

of the cherries’ effervescent blossoming into the ether,

their tiny china on a weather-beaten wrought iron pea-colored table with chair,

a scent of July in vague Lapins where the leaves would have been were it a Camellia sinensis whose tiny white flowers ain’t tea;

something you have to pass on, give away with an authentic gesture over palm fronds shadowed against the wall

in a mauve kind-of-awareness

that brings out Matisse in the Mediterranean,

probably at siesta like a breath you have to give away to make room for the next

and recognize that’s the way energy flows,

like the random steps of the Egyptian Walking onion,

its scallion agglomerations all over the garden in clumps the wandering Buddhist monk gave us an age ago

that continue on walking around us all this time.

Translate from the breath into an object of delight

like the scent of Japan in the white frills on a purple plum in the springtime when it should be

and make sure somebody else gets it.

C.M. MAYO: How might you describe the ideal reader for Sleight Work?

W. NICK HILL: My “cousin,” Quentin Deming, M. D., Chip, as he was known, and his wife, Vida Ginsberg, were role models. They treated Barbara and me like royalty, wined and dined us when we visited them in Manhattan and we knew from stories it was like that with any and all. Chip was gracious, cosmopolitan, much loved by his patients and colleagues, idiosyncratic, capable of skate boarding in his red suit on his 70th birthday, and always ready to explain how some part of your anatomy worked. His daughters called recently to tell us he had died peacefully at 99. And that a constant companion in the time up to his end was my book And We’d Understand Crows Laughing. Chip would have been the ideal reader of Sleight Work; Vida too, who was widely admired for her knowledge of theater and her sense of humor. Maybe their daughters, Maeve and Lilith, but I can’t say for sure.

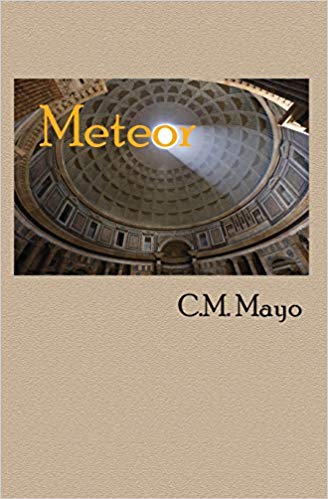

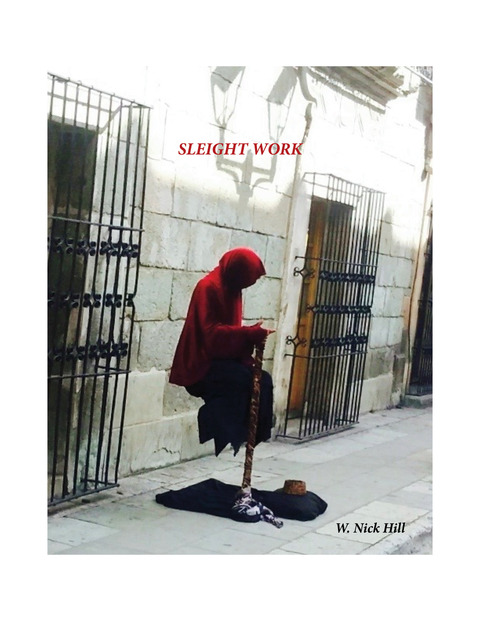

C.M. MAYO: And that cover image!?

W. NICK HILL: I write virtually every morning and those pages pile up fast! When I realized that I was working on something inchoate I began to shape the whole into a collection. Well that’s one of my principal ways of working. But in this case, I began then to look around for an image for the cover, all the while I was also investigating what would happen if I set off on my own, that is to “publish” it on my website. The image on the cover was a cell phone picture I’d taken of a busker on the Andador, the pedestrian walkway in Oaxaca, the city center on Day of the Dead, November 2017. When I’d worked out how the pose was accomplished, I was ready for the fact that the trick was after the fact, your money already in his cup. There’s an easy congress between busking and begging that goes back certainly to the picaresque tradition, and probably from time immemorial. And busking in Mexico, as you know is a worthy art. I’ve seen a Statue of Liberty across the street from an Uncle Sam, Roman Centurions, and so on. Taking money for little work is also sleight work, it’s true, though not a comely used phrase. But there’s a kind of trust the busker maintains in day long poses that she will be supported with contributions, that their bowl will not often be robbed, a presumption not so easily believed perhaps today. And then I don’t mind at all that the cover image invites the reader to consider the relation between a gift economy and the industry of book publishing in which the value of words has become more perhaps than at any other time in history the value of commerce.

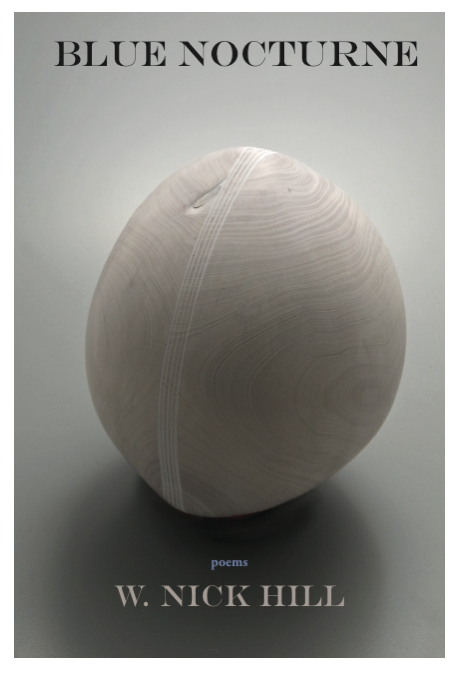

C.M. MAYO: Can you also talk a little about your previous book, Blue Nocturne, and the hexagram poems?

W. NICK HILL: At some point in 2011 I began to compose what I called hexagrams out of a need for a simple meditative practice of writing. With the I Ching in mind, I tried to write those two three line terse stanzas called hexagrams like those I had thrown using coins in the 60s and 70s to find guidance in the words of that venerable book of ancient wisdom. At least I fancied it told me appreciable things. The hexagram’s inner dynamism could change very quickly depending on the lines that moved, so there was always the possibility of surprises, changes. It was known as the Book of Changes, after all. I have also kept up with reading Tang and Sung dynasty poets, though I claim no expertise. I’m just a serial reader of Li Bo, Wang Wei, and many others. That discipline of composition continued for more than 64 days in a row and though I have all of them, only 18 or 19, depending, appear in BN.

Those little poems themselves began to very lightly sketch a consciousness that was connected to mine but wasn’t exactly. I sensed that this individual wanted to take himself, or herself, away for extended quiet, as in a remote cabin in the mountains around here in the Pacific Northwest. The speaker’s gender seemed to be male but I don’t think that it’s so clear. In the course of this quiet time alone, the speaker awaits changes for the better that may arise out of paying close attention to the surroundings, especially nighttime and dreaming, and to the writing every morning.

Another set of incidents became entangled with these six line practice pieces. During what has become my almost yearly visit to Oaxaca, specifically in 2000, a chance encounter with Una constelación de noches / A Constellation of Nights, a glossy illustrated book of an art exhibit that the Mexican poet Alberto Blanco put together in which he paired paintings and poems. That handsome coffee table book came into my hands in the quiet inner patio under a bougainvillea “roof” at the IAGO, the painter Francisco Toledo’s Institute for Graphic Arts. I have not since seen the book again, though I tried for several years to lay my hands on it. The theme of nocturnes, more easily found in music and painting of course, were still a small literary presence in my memory, particularly Alvaro Mutis’ atmospheric nocturnes that evoked his family’s coffee plantation in torrid lands. This all came together in a rush in 2013 as Blue Nocturne. The color blue, aside from the celestial, came from a personal myth. As a child in Sao Paulo, I found a book with a blue cover in a box in an unused room over the garage, the former carriage horse stable in the old house we occupied. I don’t think I read much of it then because my brother and our friends got our dad to make the space into a floor hockey rink. But the notion of that book surely underlies some part of my desire to make them.

C.M. MAYO: As a poet writing in English, which English language poets would you say have been the most influential for you? And as one who also reads Portuguese and Spanish, which poets in those languages would you say have influenced your own work?

W. NICK HILL: Allow me to answer both the above in one. In Sao Paulo, Brazil, my school mates and I spoke a bilingual mix of English and Portuguese. I loved the way those sounds danced around together! I was very much at home in Brazil. Portuguese wasn’t taught in the high school I went to when I returned to the States, so Spanish became my other language. Consequently, when I read it wasn’t English writers alone that interested me. One of the defining moments in my early life with poetry came in a flash of understanding how García Lorca made a verbal image come alive in “Romance sonámbulo,” from the Gypsy Ballads. So it’s somewhat of a twist to focus on English, but I did pay attention to Modernists, especially Ezra Pound’s ABC of Reading, because I considered it a kind of (very opinionated) handbook of poetry in English, “The Seafarer,” and the ancient Chinese, in translation, of course, a reading habit I continue with Su Tung P’o, Hsieh Ling Yun, P’o Chu-ie, and so on. I also had a lot fun reading e.e. cummings, William Carlos Williams, and for a time I thought a lot of Delmore Schwartz. Over time I went backwards, to Whitman, Dickinson, and sideways to the Beattles, Bob Dylan, and that would now have to include Leonard Cohen.

Much later, I was able to participate in a poetry workshop for a heady week with Galway Kinnell, Sharon Olds, and Michael Harper. That experience invited me to be more serious about my own writing. After that I did short-term workshops with Marie Howe, Cleopatra Mathis, and then, a chapbook workshop with Jason Shinder at the New School.

I had a career as an academic, Ph.D. in Latin American literature. I wrote a monograph, Tradición y modernidad en la poesía de Carlos Germán Belli that was published in Madrid. Belli is one of the fine poets Peru has produced. He writes about contemporary angst in Golden Age formalisms. I studied with Oscar Hahn, a powerful Chilean poet whose Mal de amor, Love’s Sickness, among many others, made a big impression. Through Hahn, I met Chilean poets, Pedro Lastra, Enrique Lihn, Nicanor Parra, Lucía Guerra, Javier Campos, and others. Javier later became my colleague at Fairfield University. Lihn became a model for my writing for a long time. He and I had long loopy talks about modernity. I was fuzzy whereas he had a clear understanding, some of which rubbed off on me, of what people were calling the Post-modern. I also developed an interest in the Summa de Maqrol el Gaviero, by the Colombian writer Alvaro Mutis. My first serious attempt to translate from Spanish were poems spoken by the existential philosopher cum sailor, Maqrol, The Lookout.

I don’t know how it is for others who teach about literature, but for me, after a time, when you’ve dealt with so many accomplished, brilliant writers and poets, it wasn’t so much that I was influenced by anyone in particular. It was more that I admired specific characteristics, or that the history of genres of writing became clearer because of the way Vallejo, for instance, who did have a serious part to play in what I wanted to do with poetry, the way he broke down previous measures of value to challenge language itself served as a path. Similarly with parts of Neruda, whose Odes touched a thread with simple language anybody could understand, like that of the ancient Chinese in English though because their poems were formally complex and were sung.

C.M. MAYO: Can you talk about writing your own poems in Spanish?

W. NICK HILL: I began writing poetry in my early 20s and those attempts were in English. After college where I studied sciences and social sciences, I went to Spain to teach English for a year and to try my hand at writing fiction. Literature of all kinds, in both English and Spanish, occupied my reading. Bilingualism was imprinted on me growing up in Brazil. Over the years I’ve drifted away from Portuguese. In any case, when I turned to my own poetry it came out mixed English-Spanish. I wrote a chapbook called Mundane Rites / Ritos mundanos that was third place in the 1997Sow’s Ear Poetry Review’s chapbook contest but they only published the winner. Some of the poems came out in the minnesota review, and others, and in the Américas Review under a pseudonym I quickly dropped, Nicolas Colina. Poems in my chapbook came directly from the Central American conflicts of the 80s and 90s, border issues, as well. One of them was an experiment in the subconscious dialogue between Cortés and La Malinche that interwove Spanish and English. I have difficulty separating my poetry from politics broadly speaking. Because bilingualism involving U.S. Latinxs is contested territory, I drifted away from “code switching,” though I continued to publish in Spanish in The Bilingual Review, Ventana Abierta from UC Santa Barbara, and in Chile. It became clear to me in my teaching that the up and coming programs of studies in the 3 principle groups of Spanish Americans in the U. S. –Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans– weren’t being represented culturally, in my university anyway, in their bona fide condition as USians who wrote as they lived, in English, Spanish, and mixed up all together. And that’s not even considering interesting writing by Central Americans, Dominicans, and others, nor much attention paid to American Indigenous languages. I got a fellowship to get caught up on Chicano Studies at Yale, and began to develop university courses that addressed those communities, in literary culture at least. After all, at Fairfield University I had a whole range of speakers in my classes: English only speaking Mexican Americans, fluent bilinguals from the Caribbean, and foreign students whose English was good. This was during a time in the 90s and early 00s that I intensified my trips to Mexico, pointedly to Oaxaca where a former student, Kurt Hackbarth, had gone to teach English. He subsequently became a Mexican citizen and writes in both English and Spanish, plays, fiction, and commentary.

I compose in Spanish, not in the same way as in English exactly, but directly, that is to say I don’t translate, though that too is inaccurate. There is a mental space, or a consciousness accompanied by intuition and emotion where languages intermingle. The closest analogy would be sexual. And it’s in that embrace of languages where I enjoy hanging out.

C.M. MAYO: What is the best, most important piece of advice you would give to a poet who would like to try translating another poet?

W. NICK HILL: After a career of teaching, I no longer want to tell anybody or teach anybody anything. But the practice dies slowly, so rather than begging off, I’ll offer thoughts based solely on my own experience.

I believe, with others, that bringing a poem into another language is a recreation and a service to readers. I have read that a translator of poetry should find work that fits their sensibilities. I’ve read the opposite too. I met someone awhile back who was translating Horace for fun. So that is probably a good start at advice. Do it because you’re wrapped up in the words, and the vision, and you like it. But this individual wasn’t going to try to publish.

“I believe, with others, that bringing a poem into another language is a recreation and a service to readers.”

If publishing is the aim, then get the rights! There are a number of ways to do that, most of which mean convincing somebody, poet or publisher –whoever holds the rights– to let you do the work, or accepts the work you’ve done. To do that you have to become the ideal reader, critic, and boatwoman to cross the mighty river between languages. Understand where compromises are required in the target language and decide throughout how to compensate. One way is to shift the untranslatable gerund over to another one that suggest a similar affect

C.M. MAYO: You have also done book length translations, for example, of Miguel Barnet’s Biography of a Runaway Slave. Can you tell a little about this experience and how it affected your own work?

W. NICK HILL: I had been tried out so to speak on Barnet’s lesser testimonial novel, Rachel’s Song, the story of a dance hall girl before Sandy Taylor at Curbstone Press asked me to do Biography. I’m not certain I’d done a very good job with Rachel who was as shallow and frivolous as cabaret life allowed in Cuba in the 20 and 30s when it was a playground for privilege. But apparently it was good enough to give me a crack at Esteban Monetejo’s story. It was a daunting challenge. Esteban was an old man when Barnet interviewed him about the saga of how he ran away from slavery, lived alone in the bush, fought in the War of Independence, and watched the Cuban Revolution triumph before he died at 105 years of age. Esteban was uneducated of course, but he was smart, wily, curious, resolute, was steeped in the lore and rituals of various Afro Cuban spiritual beliefs, and he had a sharp memory. How does such a man sound in English? Though I read U.S. slave narratives, Montejo wasn’t going to sound like them. The details of everyday life he narrated differed greatly from slaves in the U.S. in large degree because Cubans were able to hold on to parts of their heritage from Africa.

As I progressed I realized that in a very real sense as translator I was mimicking Barnet’s role in his relationship with Montejo more closely perhaps than in other translations projects. Hence the confusion of titles between my version and the previous one by Jocasta Innes who knew a lot about ethnography and didn’t want to recognize the newness of what Barnet was doing. She published her translation in England as Autobiography, thus making Montejo into the sole author. What Barnet was after was to present the runaway slave’s voice as clearly and as transparently as white man could convey. And that’s what I tried to convey in the English version of the testimony of a man who was a character, a man of contradictions, tics in his speech, and great humanity, who gave convincing details of what life as a slave and as a free man in Cuba was like before the Cuban Revolution.

I made as literal a version as I could get and then worked to shape it within all the prohibitions and permissions I was aware of as a person who bridges the gap between slave and free, Cuba and the United States. I didn’t try to round Esteban out, I left phrases in Spanish or Yoruba that had no equivalent because the original already had a Glossary that clarified details of ethnicity, history, and the like. I judged it to be acceptable to simply add to it. In all, I tried to fashion a voice of great humanity in an English that was understandable but particular. A new edition came out from Northwestern University Press in 2016, with a fine introduction by Professor Wiliam Luis.

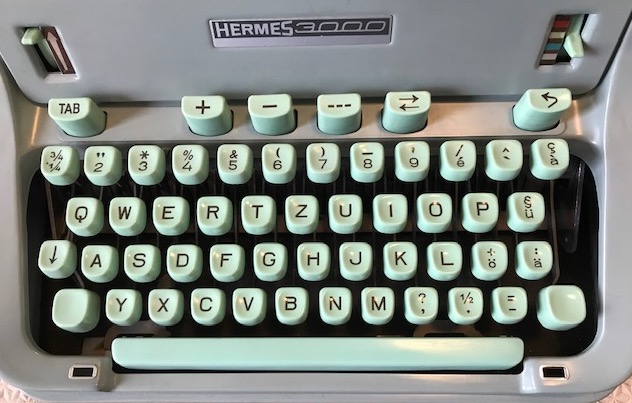

C.M. MAYO: You have been a consistently productive writer for many years. How has the Digital Revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share? And another question apropos of the Digital Revolution. At what point, if any, were you working on paper? Was working on paper necessary for you, or problematic?

W. NICK HILL: I have been much aided and hindered both by digital media. Before I left teaching I was deeply involved in using the web and programs like WebCT –programs like Chalkboard today– to help students manipulate at their own speed the conjunction of sight and sound that is central to learning another language.

After I left academics, I really dove into writing poetry. I had already withdrawn from some of those very distractions you mention because I could feel how they drew me further into time on computers and into a popular culture that relies increasingly on violence and the propagation of stereotypes. I don’t mean to say that there aren’t meaty blogs, You Tubes, and the like to enrich one’s thought, but even so it can be overwhelming, as you suggest. Thus, to say that I’m distracted from writing by elements of Virtual Reality would be erroneous however, because I’ve guarded against it. In fact, the digital has benefitted my writing in two ways.

As I said previously, I published Sleight Work on my website to take advantage of the movement to ensure access to materials remains as open and free as possible. In the world of publishing today, there are so many access points to creative work it boggles the mind. At the same time, so much of it has been infused with commercialism that I for one find it disturbing. I’m sure there are exceptions, but much of the discussion of writing on the web and in print revolves around volume of sales, numbers of prizes, and other markers of what? Subject matter? Craft? Raw writing as a practice? Justice? Art?

The second way that the Digital Revolution has not distracted me resides in the fact that I have made it a focus of my work. Awhile back I became intrigued by the Mesoamerican ballgame that was played in ancient times and is still played in some few areas of Mexico today. The game, variously called ullamalitzli, Pok-Ta-Pok, Tachli, was played with a heavy latex rubber ball five hundred years before Europeans came to colonize. I’ve been writing poems about the continuity of games in these lands. I have come to see that a continuity worthy of further exploration exists between the contemporary world of video gaming, itself a world apart, and those age-old games. This is a body of work that I’m still actively pursuing.

As for tips, I’d say the policy of following a middle course between Luddite no contact and game players who rarely see natural light is called for. And a good healthy skepticism about how electronics will deliver the biosphere from the predations of capitalism. Anthropologist David Graeber has my ear when he writes about anarchism in a compelling way in his Fragments of An Anarchist Anthropology.

I have always written on paper first and then make hard copies of what seems interesting enough to work further. The most unsettling aspect of this practice is that the pages keep on piling up. Some small fraction of those words do get digitized. Apart from that who’s going to wade through all those pounds of paper if I don’t. Which would seem to be a good argument for going paperless though I can’t shake it.

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you as a poet and translator?

W. NICK HILL: I’m preparing for another stay in my adopted city of Oaxaca, Mexico where I will finish translating Gary Lemons’ Día de los muertos that Red Hen brought out in 2016 as a coloring book. The chiste, the joke is that I’m translating it into Spanish. More realistically, I hope to polish enough of a sample to interest a poet in Mexico to sign on with me to make it ring true with the goal of seeing about a publisher. I’ve already asked Jorge Fernández Granados, but it was a year ago and was put off-handedly so he’s probably not thinking about it now. I have published a handful of poems from his Principle of Uncertainty, so I’m hoping he is amenable. In any case, Lemons’ work dances with surreal abandon that juxtaposes eccentric, intuitive images of the splendor and suffering of creatures, from burros, to dusty young gringos, and sea tortoises, all creatures encountered in Oaxaca at various times between the late 60s and the 80s. A happy, hubristic effort of mine to render this whirling dervish of words into Spanish.

In addition, I’m going to double down on a bilingual

collection of poems that builds on Mundane

Rites / Ritos mundanos and will poke around in matters related to

Americanismus, a tentative title, for new worldisms. What the adventure of

website publishing has suggested to me is that no existing publisher I know of

will chance it with a book for bilinguals not by a Latinx writer. I’m cognizant

of the political nature of cultural work and don’t want to distract from worthy

goals of U.S. Latin@s. At the moment only on the web could I present a book for

bilingual readers who might understand what I’m celebrating. Perhaps this effort

is akin to the recognition that jazz and blues are universal art forms that

honor African American originators and share their creativity even in the midst

of racism. And then there’s that ball game project at the end of a joystick.

Thanks for giving me the chance to share

with you. Keep up the good work.

Q & A: Mary Mackey, Author of The Jaguars That Prowl Our Dreams,

on Bearing Witness and Women Writers’ Archives

Q & A: Sara Mansfield Taber on Chance Particulars: A Writer’s Field Notebook

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.