“Every one of us, every single one of us, has a story,

has longings, joys and sorrows.”

––Ellen Prentiss Campbell

This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

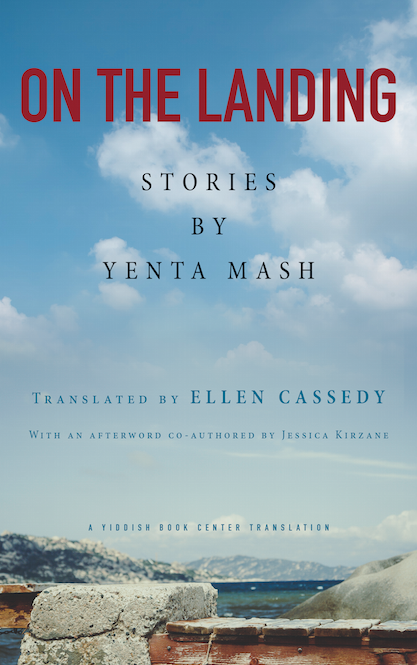

One of my favorite American writers is my esteemed amiga, Ellen Prentiss Campbell. She’s the author of a splendid historical novel, The Bowl with Gold Seams, as well as an earlier collection of short stories, Contents Under Pressure. May 1st is the pub date for her latest, Known by Heart: Collected Stories.

Here’s the catalog copy for Known by Heart:

Love is necessary but not easy in these stories of love’s joys and challenges, regrets and uncertainties. Complicated people fall in and out of love, care for each other, delight each other, disappoint each other, yearn for each other. Ellen Prentiss Campbell tells of all sorts of love: young love, lost love, love found perhaps too late, family love, love between friends. Her writing has been praised for its realism and grace. These untraditional love stories illustrate that love is essential, but not for the faint of heart.

“Keen psychological insight and a poetic flair for language bring these stories to vivid life. Campbell’s characters struggle to escape their dilemmas, whether the confines of stifling families or their own minds. To the reader’s delight, some characters pop up in multiple stories, weaving a world of recognizable human longings that are credible, poignant, and beautifully described.”

—Donna Baier Stein, author of Scenes from the Heartland

C.M. MAYO: What inspired you to write short fiction, as opposed to a novel?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: The two inspirations—short fiction, novel—aren’t mutually exclusive. Sometimes they overlap, sometimes run on parallel tracks. These stories were written over a period of many years. During that time I began a story which jumped the short story track and became my first novel The Bowl with Gold Seams. And while working on that novel, I wrote other stories, and once again, a story jumped the track and became my current novel in progress. And although this collection Known By Heart is not a novel in stories, some characters—the couple, Meg and Walker—appear in more than one story (in fact, Meg and Walker were also in a story in my first collection, Contents Under Pressure). It’s been said that short stories are close kin to poetry. That makes sense to me. I don’t write poetry, but a story does have, within it, a complete arc. It’s not a part of something smaller, it’s not a chapter in a novel. It’s a mystery why some stories jump the track and demand the longer journey.

C.M. MAYO: How has your background practicing psychotherapy informed your fiction?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: As a psychotherapist, I listened closely to stories, endeavored to help clients identify threads of meaning in their dilemmas, their pain. It’s a privilege, to do the work. I kept an absolute firewall between my work as a therapist and my writing, never wrote and would never write about my clients. But from doing the work I know that everyone of us, every single one of us, has a story, has longings, joys and sorrows. When I was listening to my clients, I was trying always to understand. And writing fiction is a different but related kind of listening—listening to my characters, trying to understand.

C.M. MAYO: If a reader were to read one story in your collection, which one would you most recommend and why?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: Catherine! You are asking me to play favorites! But if I had to choose, I would say Ruby. Partly perhaps because I wrote it most recently, it’s close to me in that immediate way. But also because—and this is partly due to my work with aging clients as a therapist, but more because of my own experience growing older—the story is told from the point of view of an older character, looking back, but still very much, very passionately engaged in the present human moment.

C.M. MAYO: As you were writing these, did you have in mind an ideal reader?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: I don’t consciously write for an ideal reader, but I do write what I love to read myself—fiction about people, relationships, the stakes and cost of loving, of trying to connect. And I am fortunate to have several close to ideal readers with whom I share my drafts, whose responses inform my work—my husband, my best friend (we’ve been reading and writing together since we were eight), a dear friend and writer I met while doing my MFA at Bennington.

C.M. MAYO: Can you describe the ideal reader for these stories as you see him or her now?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: Well, Catherine, as you know spring of 2020 is an odd season to be bringing out a book, and this is a collection of stories that are really love stories—untraditional love stories, but stories about yearning for shared connection and meaning. This is certainly a moment when we’re aware of needing each other, needing to care. So I hope for a reader with an open heart and mind, a reader who is looking to be reminded that social distancing doesn’t have to make us emotionally cold or distant from others.

C.M. MAYO: Which writers have been the most important influences for you?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: William Maxwell has been a huge influence on me. His novel So Long, See You Tomorrow, is among my very favorites. He gets right to the quiet emotional heart, and his prose is simple but lyrical. I just wrote an essay about his correspondence with Eudora Welty. Marilynne Robinson is another, my copy paperback copy of Housekeeping is almost disintegrating.

C.M. MAYO: Which writers are you reading now?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: Right this moment, this quiet interior life we’re living, is a good time for reading, isn’t it? I am reading War and Peace for the first time, with the online reading group A Public Space offers. And I am reading my way through the mysteries of Ross MacDonald. I discovered him through William Maxwell, indirectly, as he was also one of Eudora Welty’s friends and correspondents. Luckily my daughter has a shelf of his books and has lent them to me.

C.M. MAYO: How has the Digital Revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: The Digital Revolution is certainly a blessing and a curse! More blessing than curse, especially now as it enables connection with so many writers, and friends, and the news from around the world. But it is easy to fall into the rabbit hole of reading, and posting, and tweeting, and reading. I try to set some limits—have screen-free time, put my phone away. It’s harder to do now but especially during this season of quarantine I am experimenting with having the weekend be a time for not a complete break but reading only on paper. We have an old farm in Pennsylvania, without wi-fi. I love to go up there by myself and write. I even have a green Hermes 3000 in the attic and can bang away on it (just letters, not fiction)—not something my apartment house neighbors would like. I long to go up to the farm when quarantine lifts.

C.M. MAYO: Another question apropos of the Digital Revolution. At what point were you working on paper? Was working on paper necessary for you or problematic?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: I returned to writing fiction after a long hiatus about 20 years ago, and at that time started writing on my computer. So my current writing practice has been and remains working on my laptop. My fingers and my brain are totally connected on the keyboard. However when I have a draft to revise I print it out, and then make pencil edits, and re-type the new version from the print manuscript. It’s a trick author Alice Mattison taught me and I recommend it.

C.M. MAYO: For those looking to publish, what would be your most hard-earned piece of advice?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: You taught it to me at one of my first workshops with you at the Bethesda Writers Center. “Success goes to she who pays the most postage.” Of course now, no postage, but success still requires submitting, submitting, submitting, and developing the infamously thick skin necessary to cope with rejection.

C.M. MAYO: What piece of advice would you offer to another writer who is just starting out?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: Read, read, read, read—and find people who, like you, are writers who love to read.

C.M. MAYO: What important piece of advice would you offer if you could travel back in time, to your own thirty-year old self?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: Write. Don’t wait. As Ovid said, “Sing your song now, you cannot take it with you when you go.”

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you?

ELLEN PRENTISS CAMPBELL: Well, aside from my fantasy of going swimming again when the quarantine is over? (It’s a part of my routine than helps me write and stay sane!) I have a close to completed second novel I hope to get out into the world—historical fiction again, inspired by renowned psychotherapist Frieda Fromm Reichmann. And I have started researching another new novel—for the first time a novel that intends to be a novel from the outset, not a story first that jumps the track…

#

Visit Ellen Prentiss Campbell at www.ellencampbell.net.

Q & A: Mary Mackey on The Jaguars That Prowl Our Dreams

A Review of Claudio Saunt’s

West of the Revolution: An Uncommon History of 1776

A Writerly Tool for Sharpening Attentional Focus or,

The Easy Luxury of a Lap Desk

#

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.