This blog posts on Mondays. Second Mondays of the month I devote to my writing workshop students and anyone else interested in creative writing. Welcome!

> For the archive of workshop posts click here.

Those of you who follow me here know that I am fascinated by attentional management and the creative process. Of late I have posted here on my advances in email management; finding time for writing (gimungous swaths of it!); and most recently, my distraction-free smartphone (which post includes an app evaluation flowchart to tailor-make your own, should you feel so inclined).

That last post about the smartphone appeared on the eve of the publication of Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism. Because I am a fan of Newport’s books, especially Deep Work, which I recommend as vital reading for writers, of any age and any level of experience, I expected Digital Minimalism to be good. As I noted in that post, if nothing else, in broadening our ability to think about the technology we use, Newport’s term “digital minimalism” is an important contribution in itself.

Reader, Digital Minimalism is beyond superb. It is a healing book, on many and profound levels, and I believe that it is not only vital reading for writers, but for anyone who finds themselves staring at a screen more often and for longer than they know is good for them– and, alas, these days, that would be just about everybody. (Including parents.)

In Digital Minimalism Newport says much of what I have said here at Madam Mayo (I found myself nodding, yes, yes, at almost every page), but he goes thirty miles higher and a loop-de-loop beyond.

And perhaps most importantly, for the general reader looking for something in the burgeoning self-help genre addressing the behavioral addictions of our Digital Age, as a tenured professor of Computer Science at an elite university, Cal Newport has authority rarer than an orchid in the Sahara.

My intention in this week’s post is not to provide a full review of Digital Minimalism, but rather to focus on one chapter, “Reclaim Lesiure,” and, more generally, the importance for writers of quality leisure.

QUALITY LEISURE

Writes Newport:

“The more I study this topic, the more it becomes clear to me that low-quality digital distractions play a more important role in people’s lives than they imagine. In recent years, as the boundary between work and life blends, jobs become more demanding, and community traditions degrade, more and more people are failing to cultivate the high-quality leisure lives …crucial for human happiness. This leaves a void that would be near unbearable if confronted, but that can be ignored wih the help of digital noise. It’s now easy to fill the gaps between work and caring for your family and sleep by pulling out a smartphone or tablet, and numbing yourself with mindless swiping and tapping. Erecting barriers against the existential is not new–before YouTube we had (and still have) mindless television and heavy drinking to help avoid deeper questions–but the advanced technologies of the twenty-first century attention economy are particularly effective at this task.” (p.168)

I think that bears repeating.

“Erecting barriers against the existential is not new–before YouTube we had (and still have) mindless television and heavy drinking to help avoid deeper questions–but the advanced technologies of the twenty-first century attention economy are particularly effective at this task.” — Cal Newport

Newports recounts the experience of a writer who tried to go cold turkey from digital distractions. As that writer summed it up, it was “Torture.” Writes Newport:

“[He] felt uncomfortable, in other words, not because he was craving a particular digital habit, but because he didn’t know what to do with himself once his general access to the world of connected screens was removed.” (p.168)

Then:

“If you want to succeed with digital minimalism, you cannot ignore this reality… The most successful digital minimalists, therefore, tend to start their conversion by renovating what they do with their free time–cultivating high-quality leisure before culling the worst of their digital habits… When the void is filled, you no longer need distractions to help you avoid it.” (pp.168-169)

NOT THE DREAMTIME OF A CHARTREUSE MOON

OR,

THE PERILS OF PROCRASTINATION

As anyone who has taken on writing a book or three knows, only in the dreamtime of a chartreuse moon do they “write themselves.” It happens. But the experience is more often one of initial enthusiasm soon weighted down by one frustration and then twenty-nine others, delays for good reasons, for stupid reasons, more frustrations, distractions galore… and so, slowly, or quickly, a slide into the warmly inviting moist sand of procrastination.

Some books escape this trap. Most do not because the writer soon feels bad about having procrastinated–oh, very bad– and on top of this, in march the clanking, hammering, pounding round-n-round of woulda-coulda-shouldas… which makes the mere thought of the book so disagreeable that… eventually… it sinks deeper into the quicksand… and deeper…. And there it dies.

So how did I manage to write so many books, including the epic historical novel, The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire? A novel, moreover, that deals with Mexico’s most complex transnational episode and recounts it by means of a Jamesian roving omniscient point of view? Whatever you may think of my novel, were you to read it, I am sure you could agree that it was not a modest undertaking. I won’t tote up all my challenges and frustrations over the eight years I needed to research and write it. For purposes of this blog post, the answer to the question is that, apart from a perhaps unusual streak of tenaciousness in my personality, when the going got really funky with The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, I happened upon the lifesaver–I grabbed it!– of psychologist Neil Fiore’s The Now Habit.

And now here I am in the midst of another multi-year book project– multi-year by its nature–but also one that, alas, has been interrupted by two other books, a death in the family, and two household moves… I was starting to sense a bit of dampness there in the encroaching sand, as it were. But then, in one of the boxes I opened after my latest move, I found again my dog-eared copy of The Now Habit. I reread it, and I can report that Fiore’s advice is as consolingly golden as ever.

And then, after reading Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism, in the light and freshness of that, I sat down and went through The Now Habit yet again.

It was eerie to be reading Fiore’s The Now Habit in 2019, for it appeared in 1989, before anyone, outside a coterie of high-tech scientists and miltary people, had more than a notion, if that, of the Internet.

When I first read The Now Habit in the early 2000s, email had become a thing, but only a few writers had one of those newfangled things called “websites.” I did not yet know of a single one with a blog (I don’t think I’d yet heard of blogs). Cell phones were just phones. To get to school, we walked a mile in the snow without shoes (just kidding). For mindless procrastination there were trashy fiction, newspapers, magazines, and TV on tap, ever and always. In short, writers have always had to battle procrastination, albeit relatively low-octane stuff compared to the engineered-to-be-addictive apps of today.

But back to the question of quality leisure.

Of immense value for me in Fiore’s The Now Habit was the chapter “Guilt-Free Play, Quality Work.” Speaking to us from a time essentially free from “digital distractions,” Fiore says much the same thing as does Newport: for health, happiness, and productivity, we need quality leisure– or, as Fiore calls it, “guilt-free play.”

Writes Fiore:

“Attempting to skimp on holidays, rest, and exercise leads to suppression of the spirit and motivation as life begins to look like all spinach and no dessert… we need guilt-free play to provide us with periods of physical and mental renewal.”

It’s counterintuitive: when we seriously, urgently want and need to get work done, why first schedule play?!

Writes Fiore:

“Enjoying guilt-free play is part of a cycle that will lead you to higher levels of quality, creative work. The cycle follows a pattern that usually begins with guilt-free play, or at least the scheduling of it. That gives you a sense of freedom about your life that enables you to more easily settle into a short period of quality work. Having completed some quality work on your project, your feeling of self-control increases, as does your confidence in your ability to concentrate and to creatively resolve problems. In turn your capacity to enjoy quality, guilt-free play grows.” (p.82)

Play and work enhance one another in this cycle:

“…You are now well-rested, inspired, and ready for greater quality work. Guilt-free, creative play excites you with motivation to return to work.” (p.82)

I would urge anyone who wants to overcome procrastination to carefully read Fiore’s The Now Habit; he has much to say about the ways over-work can lead to procrastination, and the precise way to schedule guilt-free play with what he calls an “unschedule,” and how to overcome blocks to action. (Much of this good old-fashioned, yet oft overlooked, common sense, for example, what he calls “Grandma’s Principle,” that your scheduled guilt-free play should come after a good, solid half hour of quality work– “your ice cream always comes after you eat your spinach”.) My purpose here is not to review Fiore’s book however, but to focus on the counterintuitive importance for writers of quality leisure.

“GUILT FREE PLAY” AND “QUALITY LEISURE”

First, it should be triple-underlined that the “quality” of leisure is not necessarily related to its cost. Golf resorts, wide-screen TV manufacturers, purveyors of recreational vehicles, time-shares, sports equipment, Princess Cruises, et al would like you to imagine that what they’re selling is “quality leisure,” and the more expensive the upgrades the better!

But “quality leisure” could be an activity as pennywise as sitting in a chair in your livingroom and knitting a scarf from a ball of yarn that had been stashed in your closet for the past 20 years. Or, say, baking peanutbutter cookies; playing with your dog; walking out to the park and tossing around a frisbee with a friend. Biking to your public library to read War & Peace. Or playing baseball, curling, taking a yoga class, doing yoga on your own in your backyard, or on the beach at dawn! Scottish country dancing, baking bread, watching Casablanca at your local film school’s movie festival. Learning to play the guitar or the kazoo. Baking lasagne. Casting bronze sculpture! Or squishing together a super weird alien head the size of your fist out of papier mache!

In sum, “quality leisure” can be pretty much any activity that you truly enjoy doing and that you find energizing. (Hint: TV watching and pecking at the smartphone don’t count. Neither does bar-hopping or sitting around toking weed.) Newport has more to say about identifying and pursuing quality leisure. Before I return to that, a brief note about the “artist date.”

THE ARTIST’S WAY

By this point I imagine that many of you writerly readers may be thinking, didn’t Julia Cameron say something like this in The Artist’s Way?

Indeed she did. Cameron’s concept, a potent one, is what she calls “the artist date.” The idea is that this is scheduled quality leisure (to use Newport’s term) / guilt-free play (to use Fiore’s) but you go alone— absolutely not with someone else–and do something that nurtures your artist self. For me it might be something like a visit to a museum, reading a Willa Cather novel for an hour in a favorite coffee shop, or attending an organ concert. (In one of my most challenging moments in writing The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, one “artist date” I made for myself was to attend a planetarium show. Of all things.) Some people might like to get out the crayons or the Play-Dough. Of course, there’s no formula; what nurtures one artist, or writer, might not another.

So, advises Cameron, if you want to get some good writing done, go forth, by yourself, at a scheduled time, and do some fun and possibly wacky-nerdy thing!

Cameron’s The Artist’s Way was originally published in 1991, before the tsunami of digital technologies swept over our world, and yet like Fiore’s The Now Habit, it offers wise and timeless advice for writers. Cameron has a New Age spiritual slant, however, and that isn’t every Atheist’s slug of coffee. With that caveat, I warmly recommend The Artist’s Way.

CAL NEWPORT’S LEISURE LESSONS

Back to our computer professor and attentional focus expert Cal Newport and his latest, Digital Minimalism. In the chapter “Reclaim Lesiure,” Newport offers specific insights into which types of leisure are most effective for filling the void otherwise taken by low-quality digital distractions, and for enhancing well-being and productivity. These are those endeavors that:

(1) “prioritize demanding activity over passive consumption”;

(2) “use skills to produce valuable things in the physical world”; and

(3) tend to be those “that require real world, structured social interactions.”

Newport is not talking about eliminating digital technology, and in fact he points out ways in which websites, email, social media and more digital technologies can assist us in engaging in more and higher quality leisure. There is, Newport concedes, “a complex relationship between high-quality leisure and digital technology.” In my own case, I recently found out about and registered for a university extension course (which I attended in person) on a website. Many similar examples of how texting, social media, and YouTube, can assist and enhance real world meetings and activities no doubt pop into your mind. Newport stresses: “The state I’m helping you escape is one in which passive interaction with your screens is your primary leisure.”

“The state I’m helping you escape is one in which passive interaction with your screens is your primary leisure.”

— Cal Newport

Newport concludes his chapter “Reclaim Leisure” with four practices, each amply explained, argued, and with illuminating examples:

- Fix or build something every week;

- Schedule your low-quality leisure;

- Join something;

- Follow leisure plans, both seasonal and weekly, stating both the objectives and the habits you aim to establish.

AND TO CONCLUDE WITH FRIEDRICH DÜRRENMATT

Here is an example of one writer’s quality leisure activity: Swiss writer, playwright and artist Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921-1990) painted the bathroom adjacent to his office. This is a partial view, of side wall, back wall, and ceiling. I decline to publish here the principal appurtenance.

Thanks to poet Joseph Hutchison, who recommended Dürrenmatt’s work to me, as I am temporarly living in the area, I made it, shall we say, one of my “quality leisure” activities to visit the house / museum, now the Centre Dürrenmatt Neuchâtel. (I would also call this visit “guilt-free play,” to use Neil Fiore’s term, but not an “artist’s date,” as Julia Cameron defines it, because I did not go alone.)

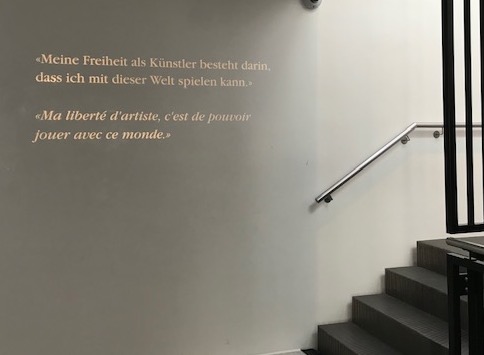

In the museum:

Here is the writer at his desk, as shown on the cover of this book (which I would translate as Dürrenmatt: His Life in Pictures):

The view of Lake Neuchâtel from his terrace:

More anon.

Marfa Mondays Podcast #8: A Spell at Chinati Hotsprings

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.