As those of you following this blog well know, I’m at work on a book about Far West Texas (that’s Texas west of the Pecos) and so reading deep into the history of the wider region that is now Texas and northern Mexico– for it all connects. I’m not reporting on each and every book I come across, but now and then I read one that, in taking both my understanding and my curiosity to a fresh level, prompts me to order my thoughts with a review and/or interview the author, should he or she be alive and willing. (See for example, Q & As with Raymond Caballero, Paul Cool, and John Tutino). Carolina Castillo Crimm’s deeply researched De León: A Tejano Family History is one of those.

We often hear about the Tejanos (Mexican Texans or, as you please, Texan Mexicans) in Mexican and Texas history, but who were they? Crimm’s De León provides an intimate glimpse of one of the first and most influential Tejano families though several generations, beginning with Don Martín de Léon and his wife Doña Patricia de la Garza, the founders of the de Léon colony and the town of Victoria on the coastal plains of Texas in the early 19th century. They and their descendants weathered Mexican civil wars; Comanche attacks; cattle rustlers; cholera; the Texas Revolution of 1835-36; the massive influx of “Anglo” immigrants; exile and legal battles to reclaim their land; the US Civil War and Reconstruction; and, into the late 19th century, the rise of the railroads and the cattle ranching industry.

C.M. MAYO: As historian Arnoldo de León commented, your study of a Tejano family “confirms what other historians have said (but not buttressed with this kind of detail) about Mexican Americans in history: that they are resilient in the face of adversity, that they adjusted to an Anglo American political environment after 1836 with a degree of success, and that their absence in Texas history books is explained by a neglect of the primary sources.”

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: Thank you for the opportunity to talk about the De León family of Victoria, Texas, one of the early founding families of Texas. As far as I know, Arnoldo de León is not related to the De León family of Victoria although you never know. He has been influential in encouraging many students to study the Hispanic world both past and present.

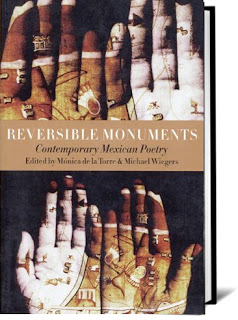

I am grateful to be part of a growing field of historians focusing on early Hispanic settlement in Texas. These so-called Borderlanders were originally inspired by Arnoldo de León and David Weber. Since then, there have been many more scholars who have delved into this area and produced excellent studies on this period. Among them are Dr. Frank de la Teja, Dr. Andrés Tijerina, Dr. Armando Alonso, Dr. Francis X. Galan, among many others.

There are also dozens of new, up-and-coming young historians working in the field of the Borderlands. It is thrilling to see so many people searching through primary sources to discover the histories of these early settlers.

C.M. MAYO: And a related question: You mention in your acknowledgements that Nettie Lee Benson had been one of your mentors. She was such a towering figure among historians of Latin America that the University of Texas Library’s Latin American collection is named after her. Can you share a memory or two about Nettie Lee Benson, how you met her, what you remember of her?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: I was fortunate enough to arrive at the University of Texas at Austin in 1989 while Dr. Benson, or Miss Nettie as one of my fellow students called her, was still teaching her course on Mexican History and the Borderlands. I had mistakenly assumed that the Latin American Collection at UT had been named for her because she was the wife of some oilman who had donated millions to the University. I was wrong.

As it turned out, she had been a librarian at UT during the 1940s. She made it her mission to take the funds she was given by the university and invest the money in books and materials from Mexico and Latin America. Each summer, she would take what, in reality, was a pittance and travel throughout Mexico. She bought, traded or salvaged materials everywhere she could. On one occasion she found a stack of old dissertations from the UNAM at a pawn shop. They were about to be destroyed but she bought them for fifty cents each, thereby rescuing a precious heritage. Each evening, she would go back to her room and wrap up her finds in brown paper and string and send them back to the library at UT. She did this every summer for years.

At last, Eugene C. Barker (for whom the Texas collection was named) encouraged her to begin work on a Ph.D. in Mexican History. Working part-time, she completed her degree and became a professor in the History Department. She continued to work at the library and to add to the collection which eventually was renamed in her honor. Students still remember her falsetto voice echoing through the stacks as she asked what each of us was working on then led us directly to some seminal book on our particular topic. She spent her life helping students explore the stacks that she created.

Dr. Benson was awarded the Aguila Azteca by the Mexican government, the highest honor that can be given to a foreigner, for her work on the Provincial Deputations of the 1820s. Her on-going encouragement of students working in the field has led to the production of hundreds of works on Mexican and Borderlands History.

There have been some Mexican scholars who have resented the removal of so much material from Mexico. They maintain that the books should be in Mexican libraries, not in the United States. As I have seen, however, Mexican libraries often do not have the funding to protect these priceless treasures. I have been in archives in Matamoros where there are bugs eating away at the paper, or in Saltillo where burned archives were only rescued by accident when a historian/diner at an out-door restaurant noticed the bits of burning paper sifting down from next door. The material at the University of Texas has been preserved and protected and is accessible to scholars from all over the world. Admittedly, Mexicans do have to travel to Austin to find the materials, but at least it is available.

C.M. MAYO: You also write that Nettie Lee Benson set you on your path. Can you talk more about that, and what inspired you to write De León?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: I started on my Ph.D. at the University of Texas without any sure direction or goal in mind. As a Mexican, I wanted very much to focus on the early Hispanics of Texas. Miss Nettie Lee suggested I work on Martín de León, the only successful Hispanic Empresario in early Texas. The problem then, and now, was the lack of sources. There were no diaries or letters, but with Nettie Lee’s help, I began to discover court records, county records, land records, and the last will and testament of Doña Patricia de León. I was also fortunate to find many of the descendants of the De León family who provided invaluable assistance in writing the book.

C.M. MAYO: You tell the story of the matriarch of the de León clan, Doña Patricia, who lived a long life filled with success but also struggle and heartbreak. And one of the key contributions of De León is to underline the role of Hispanic women settlers in Texas and, by their example, their influence on Texas laws pertaining to women. Can you talk about that a bit?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: I had not originally focused on Doña Patricia or the women of the De León clan. As with many studies of Texas history, the women were often relegated to background roles. As I explored the sources, however, I began to see that the Victoria settlement would not have existed without the efforts of Doña Patricia and her daughters and daughters-in-law.

Patricia, evidently from a very good family at Soto la Marina, had received an immense dowry of $9,000 pesos. This was at a time when most dowries in Monterrey averaged less than $5,000. Some might say she gave up the money to her husband, Martín, to fund the ranches in Texas. Considering her later careful use of money, I prefer to think she invested the money in the future of her family. And it paid off handsomely. She was able to recoup the money when she needed it most by selling the Texas family ranch in 1836 to a New Orleans real estate broker for a handsome profit. But Patricia also donated land. The lovely St. Mary’s Catholic Church sits on land donated by Doña Patricia to the Catholic Church.

Doña Patricia taught her daughters to fight for their rights when they returned to Texas in 1845. Not only did she enter the American courts to regain family land, but she encouraged her offspring to regain land that had been usurped by unscrupulous settlers. She held mortgages on land and taught her daughters to do the same. Luz Escalera, wife of eldest-son Fernando, and Matiana Benavides, a grand-daughter, held a mortgage on land owned by an uncle. When he didn’t pay up, family or no, they foreclosed on him, leaving him only the 20 acres around his ranch house.

At a time when Hispanics could not borrow from Anglo banks, Hispanic women were often the money-lenders within the Mexican community. They learned to be tough business women. It will remain a mystery why she turned on her eldest son, Fernando. In her will, she forgives all the debts owed to her by her descendants, except for the money owed her by Fernando. That money was to be collected by his brothers and sisters.

C.M. MAYO: What comes through clearly to me in De León is that the early Tejano settlers, such as Martín de León, were neither wealthy nor campesinos (peasants), but part of an emerging and literate middle class. Yet throughout many decades of the 19th century the Tejanos had to fight both the Comanches and, depending on where they placed their loyalties, various factions for or against Spain, Mexico City, the Texians, and then the Confederacy. What stands out is that these decisions were not unanimous in the Tejano community, and they were fraught with terrible risk.

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: Yes, as Dr. de la Teja has pointed out, the Texas ranchers were not wealthy but they were not poverty-stricken either. The de León family employed a teacher on the ranch to educate their children. And not all the children agreed on which side to choose. I suspect Patricia’s Christmas gatherings were a trifle tense during the years of Mexican Independence when some of her offspring sided with the Liberals while others chose the Conservatives. Things got even worse during the Texas Revolution.

C.M. MAYO: Until recent times the story of the fall of the Alamo came across as a simple story of brave Texians vs dastardly Santa Anna. Do you see your book as part of the impetus to enrich that particular narrative?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: Yes, certainly. During the Texas Revolution, half the De León family sided with the Texians while others supported the legally constituted Mexican government, even if it was Santa Anna.

The decades from 1800 through the Civil War, were a time during which there were dangerous decisions to be made. The wrong decision could result in being shot by one side or the other. Many of the Mexican ranchers learned from bitter experience to keep their heads down and their mouths shut or get out of the way. General Joaquín de Arredondo’s 1813 attack at the Battle of Medina and the later executions of Liberals, or Revolutionaries, in San Antonio was a difficult time for everyone in Texas. Doña Patricia had good reason to insist on removing her family to Soto la Marina for safety during these years, and again in 1836 to escape to New Orleans during the lawlessness of the Republic of Texas. But she always came back.

C.M. MAYO: You mention that during the US Civil War many Tejanos, including members of the de León family, engaged in the cotton and transport trades to benefit the Confederacy. I note that Evaristo Madero, grandfather of the subject of my recent book, also made his first fortune in this trade. My question is, do you see the de Leóns as part of the broader fabric of a culture of entrepreneurship found throughout the north of Mexico?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: The Spanish and then the Mexican government had restricted trade for generations (1713 to 1821) thereby preventing much in the way of entrepreneurship for the ranchers of Texas. They could sell hides and lard but there was little else of value in Texas that could be transported and sold. The Anglo settlers, in particular the Irish from the Refugio area, learned to profit from the sale of cattle from their Mexican rancher neighbors.

Once the borders were opened to trade after 1836, the Mexicans improved on their cattle trade and profited by selling corn and vegetables to the incoming colonists. They also made a profit by carrying goods in carts to the coast. As soon as the Texians saw there was a profit to be made, however, the Cart Wars of the 1850s broke out, and the Tejanos were cut out of the trade. They continued to profit wherever they could, and wherever the Texians would permit.

C.M. MAYO: It is impossible to read Texas history without the mention of the strains and struggles between the so-called Anglos and Tejanos, as if the two communities were sealed off from one another under two bell jars. Yet of course they were not. You mention the tensions and the struggles the de León family faced in defending their dignity and their land titles against Anglo newcomers at various points in the 19th century, but you also mention their long-time friendship with the Linn family.

Can you talk a little more about the Linns?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: Martín de León needed settlers to establish his Empresario grant. He brought some from Mexico, but there were some settlers already squatting on the land he had been granted. Rather than get rid of them, he simply incorporated them into his colony. Although some said he was a “cranky old man” as an Empresario (he was, after all, in his 60s), he accepted people of all nationalities into his colony. Fernando, his eldest son, became very close to the Linn family. Just as the De León family helped the Linns during the Mexican period (Edward Linn became their surveryor), they returned the favor when Texas became a State. Fernando was able to count on the Linns (John Linn became a Texas Senator) for help with legal problems.

I found that the early settlers, both Texian and Tejano, who had helped each other survive Indian raids and droughts and hard times in the years from 1821 to 1836 became loyal friends, regardless of nationality. The arrival of new settlers after 1836, however, who had not had those close relationships, created an atmosphere of antipathy and racial hatred against the Mexicans. Fortunately, there were still a few of the supportive old Texian families who protected their Tejano friends and called them the “Old Spanish Families.” This didn’t prevent the killings of the Mexican families by mobs during the 1870s or the mass murders by the Texas Rangers during the 1920s.

C.M. MAYO: At various points you mention a slave owned by Fernando de León and later inherited by his adopted son Frank, and that Frank tried to manumit him but the laws of Texas at that time would not permit it. Do you know his name and what became of him?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: Unhappily, I do not know what happened to the slave. It is possible that Frank’s will, if one were able to find it, might indicate a name or what happened to him. Most Mexicans were opposed to slavery which made the years of the Civil War difficult for them. Unlike the Germans, however, they kept their opinions to themselves and avoided getting hung. They created guard units to protect the coast from Union troops, but only one of the de León grandsons actually fought with the Confederate troops.

C.M. MAYO: You managed to keep straight several generations of a sprawling family. I can only begin to imagine how much work it must have been just to keep your research in order! For readers who may be working on their own opus, can you offer your best organizational tip?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: Any genealogical study that covers several generations is challenging. Rather than just tracing one line, where one can safely ignore all but one of the children of each generation, I created a large wall chart with all of the various children, each of their spouses, and their descendants. Where it gets complicated is with the families of the in-laws who are equally important as brothers- or sisters-in-laws. More charts, more wall space.

As anyone in South Texas will tell you: “Todos somos primos.”* And it is true. Once you connect in-laws and godparents, the network of relations is truly a Gordian knot. I found out, to my surprise, that my Castillo family who lived in the Refugio area from the 1790s to the 1870s, were distantly related to the de León family as well.

*We’re all cousins.

C.M. MAYO: Your book came out in 2003. What are the reactions that surprised you, and what are the ones that gratified you?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: I was very pleased to receive several awards from the Sons of the Republic of Texas, from the San Antonio Conservancy, and from the Catholic scholars. To have Arnoldo de León say such kind things about the book was a real honor.

I should probably not have been surprised to find that some Tejano scholars were opposed to my book. They felt that a blonde Gringa should not be writing books about Mexican land loss. I don’t “pass” since I don’t look Hispanic. I had a rather heated altercation with one of my colleagues at a conference about whether I understood how difficult it had been for Mexicans in Texas at the time. They were certain I was just another do-gooder Anglo trying to put a better light on the challenges facing Tejanos during the 1800s and their survival in spite of the difficulties. I was glad to be able to prove them wrong.

In the course of my research, I had learned that my Castillo family had lost their Refugio land in an 1870s court case to a (now) wealthy Texan family. A gunfight resulted in which one of the Anglos was shot. A lynch mob was formed and the Castillo brothers had to make a run for the border to avoid the noose. The Castillo family left Texas and lost their land. Some say it was sold, others that it was stolen. They reestablished a large ranch outside Reynosa at Charco Escondido on the Mexican side and continued to prosper as ranchers until the Mexican Revolution when they returned to the United States. So, yes, I may not look Mexican, but my family does understand land loss.

C.M. MAYO: What are you working on now?

CAROLINA CASTILLO CRIMM: As you can imagine, my interest is still focused on writing about Hispanics on the border and in Texas. I have started to write the story of the Castillo land loss and have already gotten several chapters into it. However, inspired by Americo Paredes, I wanted to go back and look at what formed the early Tejanos. Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Hummingbird’s Daughter has certainly helped.

Scandalizing though it is for a historian, now that I am retired, I have kicked over the traces and turned to fiction. I am working on a series of three novels on the 1770s in New Spain and the impact of the Bourbon Reforms. I’ve based my characters in large part on the social gulf that existed between the criollos or mestizos, like Martín who may have been a low class muleteer who made good, and Patricia, the daughter of a wealthy Spanish family. Since the story (in the third book) carries us into 1777, Bernardo de Gálvez and his defense of the American Revolution plays a part as well. The first two novels are finished and are in the editing stages. The third should be done soon. Now, I just need to find an agent and publisher. My usual publishers–the university presses–don’t do fiction.

Thanks for the opportunity to share the story of the De León saga with your readers. My website is at www.carolinacastillocrimm.com and De León is available through my web site or through amazon.

C.M. MAYO: Immense thanks to you, Carolina, and mucha suerte with your novels.

P.S. Check out Carolina Castillo Crimm’s website, and be sure to watch the video of her fascinating talk about Bernardo de Gálvez.

Blood Over Salt in Borderlands Texas:

Q & A with Paul Cool, Author of Salt Wars

Q & A with David A. Taylor, Author of Cork Wars:

Intrigue and Industry in World War II

Notes on Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s The Railway Journey:

The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.