This year I’ve been posting a Q & A with a fellow writer on the fourth Monday of the month, and while I have every intention of continuing to do so, this Monday instead herewith some notes on the epic novel by the artist who, back in 2001, passed over to the Great Beyond: Tom Lea.

> Tom Lea biography

> Tom Lea’s artworks in El Paso

“It is part and parcel of your culture and I think you should cherish it,” says Italian art historian Luciano Cheles of the surprisingly little-known works of El Paso, Texas painter and writer Tom Lea. And encouraging that is precisely what Adair Margo has been doing with great verve for the past many years with the website and educational programs of the Tom Lea Institute. I had the immense privilege of attending Margo’s talk about Tom Lea at the Bullock Museum in Austin back on October 15, 2015. (And by felicitous happenstance, I sat next to Luciano Cheles.) More about that anon.

Here is the must-see 5 minute video with what Cheles has to say about Lea’s artwork:

For more on Lea’s and The Wonderful Country’s place in the canon, see Marcia Hatfield Daudistel’s majestic anthology, Literary El Paso (TCU Press, 2009).

WILDEST WEST EL PASO

This post is prompted by my work-in-progress about Far West Texas (…stay tuned for more podcasts…) At long, belated last I have tackled Tom Lea’s epic historical novel of El Paso.

I am happy to report that The Wonderful Country is wonderful indeed, a masterpiece not only of works set in El Paso, but in the genre of the Western, and indeed in all of American fiction.

These days most literary readers, and especially those out on the coasts, tend to turn their noses up at Westerns. Dear curious and adventurous reader, if that describes you, be assured that to overlook reading The Wonderful Country is to miss out on something very fine in U.S. literary heritage. The Wonderful Country was popular in its day, back in the 1950s, but it is not a typical commercial novel; it has a high order of literary quality; morever, its treatment of Mexicans and Mexico is unusually knowing and sensitive. (What would I know about that? Start here and here; my books are all here).

Set in post-Civil War El Paso, that is, the latter part of the nineteenth century, the first days of the railroad and the last of the free-roaming Apache, and published in the pre-Civil Rights era, Lea’s The Wonderful Country forthrightly portrays many of the still painful tensions in the border region. While he writes with an unusually open heart and mind, Lea is scrupulous in rendering accurate period detail. The “N” word appears! (In the mouth of a character.) There is no lack of roastin’ ‘n stabbin’ n’ shootin’ n’ scalpin’ and our hero is the son of a Confederate from Missouri. Vegetarians and those with flea-trigger hot-buttons, be forewarned.

From the catalog copy, TCU Press, 2002:

“Tom Lea’s The Wonderful Country opens as mejicano pistolero Martín Bredi is returning to El Puerto [El Paso] after a fourteen-year absence. Bredi carries a gun for the Chihuahuan war lord Cipriano Castro and is on Castro’s business in Texas. Bredi fears he will be arrested for murder once he is back across the Rio Grande. Fourteen years earlier– shortly after the end of the Civil War–when he was the boy Martin Brady, he killed the man who murdered his father and fled to Mexico where he became Martín Bredi.

“Back in Texas, other misfortunes occur to Brady. First he breaks a leg; then he falls in love with a married woman while recuperating; and, finally, to right another wrong, he kills a man.

“When Brady / Bredi returns to Mexico, the Castros distrust him as an American, and Martin is in the intolerable position of being not a man of two countries but a man without a country.

“The Wonderful Country is marvelous in its depiction of life along the Texas/Mexico border of a century-and-a-half ago. Lea brings to life a time that was wild, a time when Texas and Mexico were being settled and tamed. Lea knows the desert region of his birth as well as anyone who has ever written about El Paso and the great nation that borders it to the south.”

NOTES ON THE TCU PRESS EDITION WITH AN AFTERWORD BY JOHN O. WEST

You should be able to scare up a first edition over on www.abebooks.com, and power to you if you want to shell out the clams for a fine first with intact dustjacket and an autograph. The copy I read is the paperback reprint of 2002 available from TCU Press (and most online booksellers) which includes afterword by John O. West, a noted US-Mexico border scholar. For West’s afterword I would recommend the TCU Press paperback as your best buy (unless your main goal, buck for buck, is to beat the stock market).

As far as I know, all editions include the elegant and evocative drawings Lea made to head each chapter.

John O. West argues, and I concur:

“The story of Martin Brady is that of Thomas Wolf’s You Can’t Go Home Again, of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn; the setting in the desert Southwest gives it particular realism, but the theme makes it speak beyond the region where it grew.”

West also provides some illuminating background on the inspirations for the novel. My additional notes below.

NOTES ON THE PLACE, THE PEOPLE, AND THE EVENTS THAT INSPIRED THE NOVEL, PLUS SOME RELATED RECENT WORKS & WEBSITES

Tom Lea’s “El Puerto” is based on El Paso; Fort Jefflin, clearly inspired by Fort Bliss.

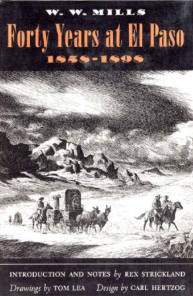

El Paso pioneer W.W. Mill’s memoir Forty Years at El Paso, 1858-1898 was Tom Lea’s major inspiration. A first edition is pricey! But it is out-of-copyright now so you can read a digitalized edition for free online.

In 1962 the El Paso-based fine art printer Carl Herzog brought out an edition of W.W. Mill’s Forty Years at El Paso illustrated by Tom Lea. Last I checked, autographed copies in good condition run upwards from about USD 125.

MORE TO EXPLORE:

> Check out the excellent El Paso Museum of History. If you ever visit El Paso, don’t miss it.

W. H. Timmons’ El Paso: A Borderlands History (Texas Western Press, 1990). Back in the 1960s, Timmons served as Chairman of the History Department at the University of Texas El Paso.

Fort Bliss actually moved around the El Paso region quite a bit in the 19th century, but you can visit the current Fort Bliss, which has an adobe museum and a modern museum– the latter perhaps of most interest for WWII aficionados. The historic parade grounds, surrounded by stately houses for senior officers, are well worth a visit.

Some of the characters in The Wonderful Country are inspired by (or mighty similar to) some real people, among them:

Joe Wakefield, mail carrier

> See the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA) Handbook on The Butterfield Overland Mail

> TSHA on William “Bigfoot” Wallace

> See Greg Sample Ely’s The Texas Frontier and the Butterfield Overland Mail

Ludwig Sterne, merchant

> See TSHA Handbook on Ernst Kohlberg

Cirpriano Castro, Chihuahuan cattle king

> Luis Terrazas

The pioneer trader MacBee

> See the Magoffin Home History

> See my post on Susan Magoffin et al, “The Harrowingly Romantic Adventure of US Trade with Mexico”

> A biography I can warmly recommend is W. H. Timmons‘ James Wiley Magoffin: Don Santiago El Paso Pioneer (Texas Western Press, 1999).

APACHES

Fuego, the Apache chief

> See TSHA on Victorio and the Chiricahua Apache Nation official webage

Both the U.S. Army and the Mexican Army went after the Apaches, and in some instances, U.S. forces chased Apaches into Mexico. In general such US Army forays seem to have been welcomed by the Mexicans, but communications in these remote areas were dicey and resentments still very raw after the US-Mexican War. Many historians writing in English about border history have not had the wherewithall to research Spanish language sources, and vice versa, so there is some low-hanging fruit here for those historians with cross-border cultural and language skills. The Apaches also have something to say about it. One recent biography of note is Kathleen P. Chamberlain’s Victorio: Apache Warrior and Chief (University of Oklahoma Press, 2007).

Another, more contemporary, take on this period is Gary Clayton Anderson’s The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1820-1875 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2005), a book that, back in 1950s, when Lea was writing The Wonderful Country, might have been unimaginable to Lea. Or so it would seem to me. I don’t know; Lea is no longer here to ask.

See also Dan L. Thrapp’s Conquest of Apachería and Eve Ball’s In the Days of Victorio: Recollections of a Warms Springs Apache.

EL PASO POLITICS

Post-Civil War El Paso politics were brutal and bloody; Lea’s novel does not exaggerate. In addition to W.W. Mill’s Forty Years in El Paso, see Paul Cool’s recent and excellent book about the El Paso Salt Wars, Salt Warriors.

TEXAS RANGERS

The hero of The Wonderful Country becomes a Texas Ranger. A crucial source for Lea, writing back in the 1950s, was James B. Gillett’s 1921 memoir, Six Years with the Texas Rangers: 1875-1881, from which Lea takes the epigraph and his title:

“Oh, how I wish I had the power to describe the wonderful country as I saw it then.”

> Check out Gilett’s page at the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco, Texas. Gillett ranched south of Alpine and upon moving to Marfa helped found the West Texas Historical Association. He died in 1937 and is buried in Marfa.

For those interested in the history of the Texas Rangers, a recent work of note, and that provides a better sense of why the Texas Rangers are so controversial– heroes to many, yet feared and even loathed by others– is The Texas Rangers and the Mexican Revolution: The Bloodiest Decade, 1910-1920 by Charles H. Harris III and Louis R. Sadler (University of New Mexico Press, 2004).

(The Texas Rangers made up a more heterogeneous group than some too easily conclude. See also the 2014 book by historian Cynthia Leal Massey, Death of a Texas Ranger. An interview with Massey is here.)

TENTH UNITED STATES CAVALRY

The Wonderful Country has a number of characters who serve in the Tenth U.S. Cavalry. The Tenth was famed for its African American “Buffalo” soldiers, and its exploits in fighting Indians, especially in Texas and then Arizona.

> See TSHA on Col. Benjamin H. Grierson

Less famous, but undeservedly so, is Lt. John Bigelow, Jr., who is the subject of a forthcoming paper I presented at last year’s Center for Big Bend Studies Conference. His younger brother, Poultney Bigelow, who published his series of articles on trailing the Apaches, was a great friend of artist Frederic Remington who illustrated many of the articles. Their father, John Bigelow, was an accomplished editor (at one point editing the New York Times), he served as President Lincoln’s ambassador to France, and had much to do with the founding of the Republican Party, the New York Public Library, the Panama Canal, and promoting Swedenborgianism. Bigelow, Sr also entertained literary celebrities including Charles Dickens and Oscar Wilde. My paper explores some of the family’s rich and varied social and political connections, John Bigelow Jr’s reports for Poultney’s magazine, his role as a nexus between the Eastern establishment and the West, and his importance as a military intellectual who anticipated the profound changes to come in 20th century warfare.

> See my Notes on John Bigelow, Jr. and

> Further Notes on John Bigelow, Jr.

NOTES ON THE 1959 MOVIE “THE WONDERFUL COUNTRY” BASED ON THE NOVEL

… Reminds me of that old joke about the goats out browsing on a hill in Hollywood. They find the can with the reel of film, they kick it open, and they start munching… The one goat says to other, well, whaddya think? The other goat chews some more. “Eh,” the goat says, “I liked the novel better.”

One of the African American “Buffalo soldiers” is played by baseball star Satchel Paige. Tom Lea himself has a cameo as the barber, Peebles.

MORE ABOUT TOM LEA’S LIFE AND WORK

The go-to resource is the webpage for the Tom Lea Institute.

Lea could be very self-depreciating. From Tom Lea: An Oral History:

“Writing is a kind of burden to me, which painting is not. I sweat and stew and fight painting, but I am not overwhelmed… by problems like I was with writing. I taught myself to write and never had any kind of a mentor or formal course… I taught myself to write by reading, reading good stuff.”

On The Wonderful Country:

“…I wanted to do something that ad been on my mind since I was a kid: Write about this borderland and the people on both sides of the river.”

“When traveling down in Mexico I never carried anything more than a little notebook because I was trying to train myself to hear rather than to see. I was trying so hard to be a good writer, you know… The hardest chapter in that book was where Martin goes with Joe Wakefield across the river in the springtime. I was trying to tell how much this fellow felt about both sides of the river. I remember I struggled and struggled for some way to express springtime and I settled it by saying, ‘A mockingbird sang on a budded cottonwood’ or something like that. I had to watch myself about using the big word. I always chose the shortest way if it could say exactly what I wanted.”

NOTES ON CRAFT: SPECIFICITY

In my workshops I often discuss what it means to see as an artist and the importance of using specific details that appeal to the senses. Lea does this so beautifully. A few examples:

“A gust of wind sished sand against the one small windowpane.” (p.16)

“They ate in the light of tallow dips, a dozen men in soggy leather, laughing and chewing, with the rain sounding on the roof, and cold drops leaking through.” (p.250)

“Slowly, under the winking high stars, they came to where they saw beyond the paleness of the sand the darkness of the brush that lined the river, and they rode toward it. They worked across a dry flat of alkali white in the starlight, with the hooves scuffling the crust in the windless silence. ” (p.306)

FURTHER MISC NOTES

From Tom Lea Month 2012, Nick Houser on Lea’s Cabeza de Vaca picture:

In my opinion, Lea’s masterwork is his 1938 mural “The Pass of the North” which is in El Paso Historic Federal Courthouse Building.

NOTES ON HIS FAMILY

Lea’s father was Tom Lea (1877-1945), who served as mayor of El Paso during the Mexican Revolution. (Alas, many Mexicans and Mexican Americans do not remember Mayor Lea fondly; this is one reason why.)

A cousin was Homer Lea, an advisor to Sun Yat Sen.

> See Lawrence M. Kaplan’s biography, Homer Lea: American Soldier of Fortune

Review by C.M. Mayo for Literal:

Bitter Waters: The Struggles of the Pecos River by Patrick Dearen

Blood Over Salt in Borderlands Texas:

Q & A with Paul Cool about Salt Warriors

On Organizing (and Twice Moving) a Working Library:

10 Lessons Learned with the Texas Bibliothek

Visit my website for more about my books, articles, and podcasts.