This year the second Monday is dedicated to a post for my writing workshop students, except when not. This post is a “not”– or rather, not exactly; I would hope that my workshop students, and indeed any and all English-language readers, may find it of interest.

This interview was an honor, and a most welcome opportunity to say some things that have been looming ever larger in my mind.

P.S. Visit Luis Felipe Lomelí’s website here.

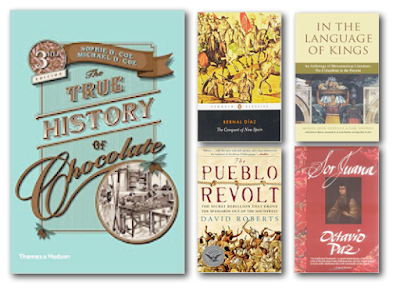

In the interview I also mention Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. I wrote about Sor Juana here and in my Kindle longform essay, “Dispatch from the Sister Republic or, Papelito Habla.” John Campion was Sor Juana’s first English translator. You can read his translation of her magnum opus on his website, worldatuningfork.com, here.

TRANSCRIPT

(WITH ENGLISH TRANSLATION):

MEXICAN WRITER LUIS FELIPE LOMELÍ

ASKS QUESTIONS IN ENGLISH;

LA ESCRITORA ESTADOUNIDENSE C.M. MAYO

CONTESTA EN ESPAÑOL

DECEMBER 2018

LUIS FELIPE LOMELÍ: Where you were born and where have you lived?

C.M. MAYO: Nací en El Paso, Texas, en la frontera, pero crecí en el norte de California, la parte ahora conocida como “Silicon Valley.” He vivido en Chicago, Washington DC, y otros lugares pero puedo decir que he pasado el mayor número de años de mi vida en la Ciudad de México.

[I was born in El Paso, Texas, on the US- Mexican border, but I grew up in northern California, in what is now “Silicon Valley.” I’ve lived in Chicago, Washington DC, and other places, but at this point I have lived more years of my life in Mexico City than anywhere else.]

LFL: Your profession?

CMM: Soy novelista, ensayista, poeta y traductora literaria.

[I am a novelist, essayist, poet, and literary translator.]

LFL: What drove you to Mexico, to live in Mexico (where and for how long) and to write about Mexico, to embrace Spanish as part of your culture?

CMM: ¡El amor! Me casé con un mexicano, un compañero de la Universidad de Chicago, y recién casados vinimos a vivir a la Ciudad de México. Han sido 32 años, la mayoría de ellos en la Ciudad de México.

[Love! I married a Mexican, a classmate at the University of Chicago, and directly after we got married we came to live in Mexico City. We’ve been married 32 years now, and most of these years we have been in Mexico City.]

LFL: What do you think about U.S. immigrants that live in Mexico, what do they do there, why are they there? Do they chose particular places to live?

CMM: Conozco mucha gente como yo, que venimos a residir en México por motivos personales. Otras también han venido por motivos profesionales, por ejemplo en la academia, en los artes y en las actividades empresariales, en todo tipo de empresas. Por supuesto allí están las comunidades de jubilados y artistas, en lugares tales como San Miguel de Allende, Ajijic, Los Cabos, y demás. A mí me parece que les ha convenido venir a México porque el clima invernal es más suave, el costo de vivir es menor que en Estados Unidos, y también por la aventura. ¡Algunas personas tienen mayores aventuras que otras!

[I know many people such as myself, who came to Mexico for personal reasons. Many also come for professional reasons, especially in academia, the arts. And others for business, all sorts of businesses. Then there are of course the retirees and artists living in San Miguel de Allende, Ajijic, Los Cabos, and so on, and it seems to me that most of them have come south because the winter weather is better, it’s cheaper to live there than the U.S., and for the adventure. Some have more adventures than others!]

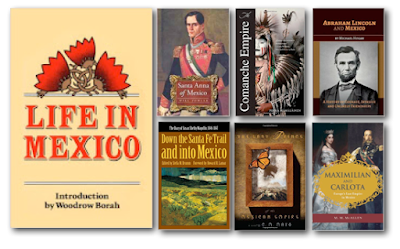

Los norteamericanos han estado viniendo a vivir en México desde hace mucho más de un siglo. En los 1840s empiezan a llegar algunos comerciantes a través del Santa Fe Trail, el camino que conecta la ciudad de St Louis, Missouri con el Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, esto es, el camino real desde Santa Fe hacia a Ciudad Chihuahua, Durango, Querétaro, y la Ciudad de México. Y después, en la segunda mitad del siglo 19, por ejemplo, muchos ingenieros estadounidenses vinieron a México, ingenieros de minas, de ferrocarriles, de petróleo. Periodistas, rancheros, hacendados, novelistas, hoteleros, misioneros. Y aún mercenarios. Por ejemplo, muchos estadounidenses lucharon en varias facciones de diversos conflictos en México, incluyendo en la Revolución. Y en algún momento inmigró un grupo de mormones. Otro de menonitas.

[Americans have been coming to live in Mexico for well over a century. We start to see a few traders coming to live in Mexico in the 1840s, coming down on the Santa Fe Trail, connecting St Louis, Missouri with the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, that is to say, the old royal road down to Ciudad Chihuahua, Durango, Querétaro, Mexico City. And later, in the second half of the 19th century, many U.S. engineers came to Mexico—mining engineers, railroad engineers, petroleum engineers. Journalists, ranchers, planation owners, novelists, hotel owners, missionaries. And even mercenaries. For example, many Americans fought in conflicts in Mexico, including in the Mexican Revolution. At one point Mormons migrated into Mexico. And Menonites.]

Uno de los personajes de mi novela está basado en Alice Green, la hija de una familia prominente de Washington DC. Su abuelo fue un ayudante del General Washington en la Guerra de Independencia. En Washington ella se casó con un diplomático mexicano, Angel de Iturbide, quién era de casualidad el segundo hijo del emperador de México, Agustín de Iturbide. Ella y su esposo vinieron a residir a la Ciudad de México en los 1850s.

[One of the characters in my novel is based on Alice Green, who was the daughter of a prominent family in Washington DC. Her grandfather was an aide-de-camp to General Washington in the American Revolution. In Washington she married a Mexican diplomat, Angel de Iturbide, who happened to be the second son of Mexico’s Emperor, Agustín de Ituride. She and her husband came to live in Mexico City in the 1850s.]

Otra historia del siglo 19, muy diferente, sobre la cual estoy escribiendo actualmente, es la de los negros seminoles, quienes eran los esclavos de los indígenas Seminoles, originalmente de Florida. Pues si, es poco conocido pero algunos indígenas tenían, compraban y vendían esclavos de descendencia africana. Poco después de que el gobierno de Estados Unidos obligó a los Seminoles a mudarse a Territorio indio, los negros seminoles se escaparon, caminando a través del desierto de Texas hacia México. El gobierno mexicano les otorgó terreno en cambio de que los hombres ayudaran al ejercito mexicano en la persecución de los apaches y otros indigenas nómadas en el norte de México. Con la conclusión de la Guerra Civil en Estados Unidos y la Emancipación de los esclavos, muchos de los seminoles negros migraron de regreso a Texas para hacer lo mismo, ayudar al Ejercito de los Estados Unidos en cazar a los apaches, comanches y otros indigenas nómadas en las Guerras Indias. Todavía existe una comunidad de los descendientes de los negros seminoles en Brackettville, Texas y otra en el norte de México.

[Another very different story, one I’m writing about now, is that of the Seminole Negros, who were the slaves of the Seminole Indians, originally in Florida. It’s little known but it’s a fact, some Indians kept and bought and sold slaves of African descent. Soon after the U.S. government forced the Seminoles and their slaves to Indian Territory, the Seminole Negros fled, trekking from Oklahoma over the Texas desert, into Mexico. In exchange for land, their men worked as scouts for the Mexican Army, which was hunting down Apaches and other nomadic indigenous peoples in northern Mexico; and after the U.S. Civil War, with Emancipation, many Seminole Negroes migrated back into Texas, to do the same work for the U.S. Army, in the Indian Wars. There is a community of the descendents of the Seminole Negroes in Brackettville, Texas, and another in northern Mexico.]

La inmigración de estadounidenses hacia México es una historia extraordinariamente rica y compleja, pues cada persona, cada familia tiene su propia historia. Es más, en México hay inmigrantes de varias partes del mundo.

[U.S. immigration to Mexico is an extraordinarily rich and complex history, or rather, many histories, for each person, each family has their own. Moreover, Mexico has immigrants from many parts of the world.]

LFL: What is your impression and/or conception about this cultural exchange?

CMM: En cuanto la comunicación intercultural entre Estados Unidos y México, yo diría que hay muchos enlaces, muchos acercamientos, mucho que tenemos en común, mucho que podemos celebrar, pero no es lo que podría ser. Creo que algunas razones de eso—algunas—tienen sus raíces por allá en el siglo 16, en la rivalidad entre la España católica y la Inglaterra protestante.

[As for US-Mexico intercultural understanding today, I would say there are many connections, many bridges, much that we all have in common, and can celebrate, but it’s not what it could be. I acually believe that some reasons for this—some— have their roots all the way back in 16th century, to the rivalry between Catholic Spain and Protestant England.]

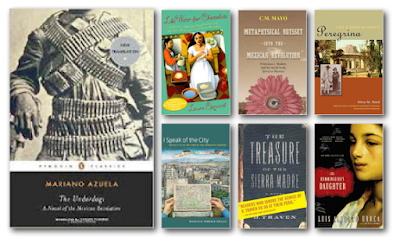

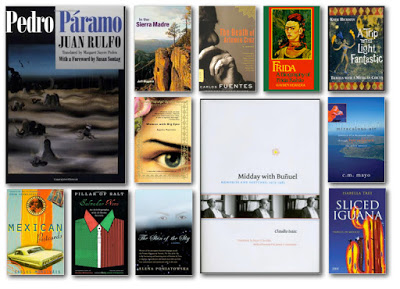

Pero enfocamos en cuestiones literarias. Hoy, un elemento, el cual es tanto una causa como un síntoma de la falta de comunicación intercultural, es que relativamente pocos libros se traducen del español al inglés o del inglés al español. Como porcentaje de libros publicados es minúsulo. Como resultado, muy, muy pocos escritores mexicanos se conocen en Estados Unidos. Octavio Paz, quién ganó el premio Nobel. Carlos Fuentes… quizá Juan Rulfo… algunos pocos lectores en inglés han oído de Carlos Monsiváis, Elena Poniatowska, Angeles Mastretta, Ignacio Solares, para nombrar unos de los distinguidos escritores contemporáneos mexicanos cuyos libros han sido traducidos al inglés. La lista de nombres conocidos disminuye en un parpadeo.

[But to focus on literary questions. Today, one factor, which is both a cause and a symptom of problems with intercultural communication, is that relatively few books are translated from Spanish into English, or from English into Spanish. As a percentage of what original work is published it’s minuscule. As a result, very, very few Mexican writers are known in the US. Octavio Paz, who won the Nobel Prize. Carlos Fuentes…maybe Juan Rulfo… a very few will have heard of Carlos Monsiváis, Elena Poniatowska, Angeles Mastretta, Ignacio Solares, to name a few of Mexico’s distinguished contemporary writers who have had books translated into English… The list of recognizable names dwindles in a blink.]

Y por cierto un escritor mexicano destacado quién debe de ser más conocido en inglés es Luis Felipe Lomelí.

[And by the way, an outstanding Mexican writer named Luis Felipe Lomelí should be much better known in English.]

En México cuando voy a una librería mexicana, en cuanto a libros de literatura traducidos del inglés, por lo general encuentro best-sellers, Harry Potter, y así, y quizá algunos clásicos. Shakespeare, por ejemplo. Ay, acabo de mencionar dos obras británicas. Edgar Allen Poe. Ernest Hemingway. Ahora que lo pienso, conozco un par de poetas mexicanos quienes les encantan los Beats, William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac. El último grito en los 1950s. Hay muchos ejemplos per, a grandes rasgos, así es la situación.

[In Mexico when I go into a Mexican bookstore, as far as books of serious literature translated from the English, I generally find best-sellers, Harry Potter, and the like, and a few classics. Shakespeare, for example. Ha, I just mentioned two British works. Edgar Allen Poe. Ernest Hemingway. Now that I think about it, I know a few Mexican poets who love the Beats, William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac. Hot stuff in the 1950s. There are many more examples but, in general terms, this is the situation.]

Podemos señalar el prejucio, la ignorancia, el conservativismo de los editores, pero podemos avanzar más por el camino de la comprehensión en reconocer, primeramente, que lectores—en todo el mundo—prefieren leer libros originalmente escritos en su propio idioma. Segundo, reconocer el gran sapo gordo del hecho de que la traducción literaria es cara. Y así debe ser, puesto que traducir todo un libro es una labor que requiere muchos conocimientos y mucho tiempo. Aún así, los traductores literarios ganen muy poco. Cuando traduzco poemas y cuentos cortos para revistas literarias, como la mayoría de los traductores literarios, no cobro, o más bien no recibo nada más que dos ejemplares de la revista. Lo hago como labor de amor, por lo general. Existen becas y otros apoyos, pero son escasos.

[We could point a finger at prejudice, at ignorance, at publishers’ conservativism, but we can go further down the road towards understanding by acknowledging firstly, that readers—all over the world— prefer to read books originally written in their own language. Secondly, there is the big fat toad of a fact that literary translation is expensive. And rightly so, because it takes a of skill to translate a book, and it takes a lot of time. Even still, translators are poorly paid. When I translate poems and short stories for literary magazines, like most literary translators, I usually do it for free, or I should say, I don’t receive anything other than a couple of copies of the magazine. I do it as a labor of love, usually. There are grants for literary translators, for publishing literary translations. But these are few.]

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Para mí, ésta historia nos dice todo: Tengo entendido que “Primero Sueño,” el magnum opus de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, la gran poeta mexicana del barroco, una monja quien fue una figura literaria monumental en las Americas del siglo 17, se traduce al inglés por primera vez hasta 1983. Afortunadamente fue hecha por John Campion, un traductor y poeta excelente. El libro está agotado no bastante puedes Googlearlo y leerlo en su página web, worldatuningfork.com. John Campion, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

[Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. For me, this sums it up: “Primero Sueño,” the magnum opus of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Mexico’s great poet of the Baroque, a nun who was a monumental literary figure in the Americas, was first translated into English only in 1983. Fortunately it was by John Campion, a fine translator and a poet himself. The book is out of print but you can Google that up and read it on his webpage, www.worldatuningfork.com. John Campion, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.]

Mi mensaje para las escuchas de esta entrevista es que una manera en que tú, como lector, puedes mejorar la comunicación intercultural, es buscar libros más allá de los best-sellers, más allá de los libros que todo el mundo lee, y en especial, buscar traducciones. Por lo general las traducciones se publican por editoriales pequeñas quienes no cuentan con muchos recursos para hacer mercadotécnia. Si no tienes el dinero para comprar un libro, es probable que la biblioteca de tu escuela o universidad o tu biblioteca pública pueda conseguirte un ejemplar. Si no lo ves en su catálogo, no seas tímido, pregúntale al bibliotecario si lo puede conseguir mediante préstamo interbibliotecario o comprarlo para la biblioteca. No pierdes nada en preguntar. Podrías ser felizmente sorprendido.

[My message for those of you listening to this interview is that one way that you, as a reader, can help improve intercultural communication is to look beyond the books on the best-seller table, read beyond the books everybody else is reading, and in particular, hunt for translations. Translations are often brought out by small presses that don’t have much marketing muscle. If you don’t have the money to buy a book, your school, university, or public library can probably get you copy—if you don’t see it in their catalogue, don’t be shy about asking the librarian to get you a copy on interlibrary loan, or even to buy it for the library. It doesn’t hurt to ask. You might be happily surprised.]

Y si tienes ganas de hacer una traducción, que sea al inglés o al español ¡házla! Por supuesto, si la obra original se encuentra en copyright y quieres publicar tu traducción, es necesario conseguir el permiso.

[And if you feel moved to translate a text, whether into English or into Spanish, give it a try! Of course, if the original work is still in copyright and you want to publish it you will need to get permission.]

Como lector, tus esfuerzos son importantes. No todo el mundo lee libros, así que para mucha gente la lectura no les parece una actividad importante. Pero los lectores tiendan a ser gentes pensantes y de acción. Un libro, aún leído por poca gente, aún por una sola persona, tiene el potencial—el potencial— de un poder enorme. Un poder para cambiar el mundo. No exagero.

[As as reader, your efforts matter. Not everyone reads books, so it might not seem all that important an activity. But those who read books, they tend to be thinkers and doers, so a book, even if read by a few people, even by one person, holds the potential—the potential— for enormous power. Power to change the world. I do not exaggerate.]

En esencia, un libro es un pensamiento grande y complejo empaquetado en un recipiente hiper-eficiente capaz de llevarlo a través del tiempo y del espacio.

[A book is, essentially, a large, complex thought packed into a hyper-efficient vessel that can carry it across time and space.]

Déjenme regresar al ejemplo de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Si no has oído de esta monja del siglo 17, en este instante a través de tu laptop o smartphone, o aún mejor, yendo a la biblioteca, lee tantito sobre su vida, algunas líneas de su poesía. Con este pequeño esfuerzo, yo creo que cambia tu concepto de México, de mujeres y del mundo. Vas a llegar a tus propias conclusiones, por supuesto, pero tu mundo será ya diferente.

[Let me return to the example of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. If you have not heard of this 17th century nun, and you take a moment on your laptop or smartphone, or better yet, to go the library and read up a bit, and you read some lines of her poetry—just that little—I think your whole view of Mexico, of women, and of the world will change. You will draw your own conclusions, of course, but your world will be changed.]

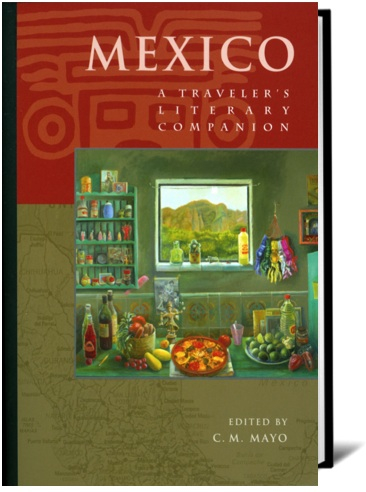

LFL: And what was your intention or the goal you pursued in editing the Mexico: A Traveler’s Literary Companion?

CMM: Es un retrato de México a través de la ficción y prosa de 24 escritores mexicanos, muchos en traducción por primera vez. No es un Who’s Who, un Quién es quién de los escritores mexicanos, aunque de hecho incluye varios escritores muy distinguidos. Más bien ofrece a los lectores en inglés una introducción a la deliciosísima variedad de la literatura mexicana y en México mismo: desde los puntos de vista cultural, social, regional. La meta fue ir más allá de los estereotipos.

[This is a portrait of Mexico in the fiction and prose of 24 Mexican writers, many in translation for the first time. It’s not meant to be a Who’s Who of Mexican writers, although it does include some distinguished writers, but rather, to provide for English-language readers an introduction to the delicious variety in Mexican writing and Mexico itself: cultural, social, regional. To blast beyond clichés!]

Armar el tomo fue para mí un reto nada fácil puesto que la mayor parte de la literatura mexicana contemporánea, por cierto la más visible, proviene de la Ciudad de México. No obstante, encontré varias obras espléndidas, por ejemplo, “La Dama de los Mares” por Agustín Cadena, un relato ubicado en la costa de Baja California, “Día y noche” por Mónica Lavín en Cuernavaca, y el relato de Araceli Ardón “No es nada mío” de Querétaro. Les invito a leer más en mi página web, www.cmmayo.com

[This was quite a job for me as editor because much of contemporary Mexican literary writing, and certainly the most visible, comes out of Mexico City. But I did find many splendid pieces, for example, Agustín Cadena’s “Lady of the Seas,” set in Baja California, Mónica Lavín’s “Day and Night” in Cuernavaca, and Araceli Ardón’s “It Is Nothing of Mine,” set in Querétaro. I invite you to read more on my website, www.cmmayo.com.]

Gracias.

[Thank you.]

#

P.S. About looking for translations, whether from English to Spanish or Spanish to English: Here’s another book you could order, or ask your library to order: Ojos del Crow / Eyes of the Cuervo by Joseph Hutchison translated by Patricia Herminia.

Tulpa Max or, Notes on the Afterlife of a Resurrection

What the Muse Sent Me About the Tenth Muse, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Visit my website for more about my books, articles, and podcasts.