“I have had numerous successful readings on Zoom. Check them out through my website at https://www.alenier.com/videos. I like the platform and I have been making opportunities for other poets through Zoom. Yes, of course, there is a future in online readings. You get a bigger more geographically diverse audience. It’s exhilarating.”— Karren Alenier

This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

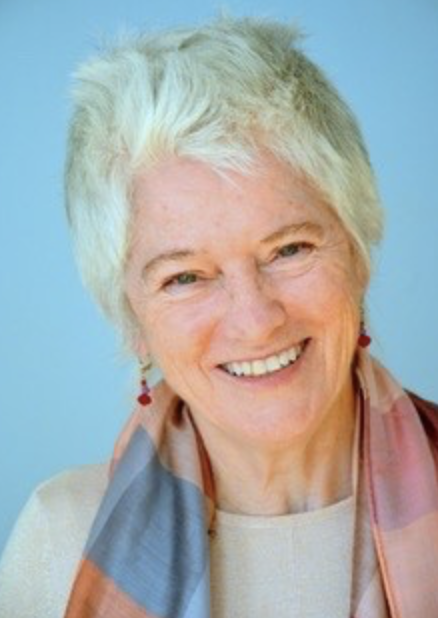

Karren Alenier is one of my very favorite poets, both for the quality of her poetry, but also for her enthusiasm for poetry and the generosity of her spirit. If memory serves, I met Karren 20 years ago when I was selected to read my work at the Joaquin Miller Cabin Poetry Series in Washington DC. And later I was delighted to learn that, in different years, an eon earlier, we had both studied with Paul Bowles in Tangiers. Karren has written about Paul and his wife Jane— read all about that in her The Anima of Paul Bowles. Since 2017 she also hosts a richly varied blog on publishing, https://alenier.blogspot.com.

I’ve been meaning to get Karren here for a Q & A for some time now; her new book, How We Hold On, makes for the perfect occasion.

C.M. MAYO: What inspired you to write How We Hold On? Can you talk about its genesis?

KARREN ALENIER: The loss of my husband Jim Rich is what inspired this manuscript, especially the poems about Jamaica. Jim loved the Jamaican poems and urged me to get them published. The model for this work was my prize-winning book Looking for Divine Transportation. Both have 4 sections beginning with family poems and a section where poems from another country are featured.

C.M. MAYO: As you were writing, did you have in mind an ideal reader?

KARREN ALENIER: Sometimes books of poetry are consciously written and other times, the work is collected. How We Hold On is a collected work driven by my desire to preserve the memory of my late spouse and the love we shared. Love poetry always has an audience. I also hoped that the poems would bring solace to some of Jim’s grieving friends.

Other readers I hope to reach are those interested in poetic form. Grace Cavalieri, always a quick study, said that I had a different strategy for each poem and by that I took it that she meant I used a wide variety of poetic forms to contain what I was feeling and expressing. For audience interested in current events, I also managed to use very new work done as letters to my great grandfather who died in the 1918 pandemic flu.

C.M. MAYO: Which poets have been the most important influences for you? And for How We Hold On in particular?

KARREN ALENIER: Normally, I would say Wallace Stevens and Gertrude Stein have been important influences and they are over all, but for this work, I would say Elizabeth Bishop (form), Ed Hirsch (absurdity), Allen Ginsberg (passion), Guillaume Apollinaire (disconnected leaps).

C.M. MAYO: Which poets and writers are you reading now?

KARREN ALENIER: Two poets who have caught my attention recently are Harryette Mullen (very Steinian) and Diane Seuss (lovely on absurdity). I read a lot of fiction. I’m currently reading Elena Ferrante’s The Lying Life of Adults. I love stories that take place in the countries of the Mediterranean.

C.M. MAYO: How has the Digital Revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to call down the Muse with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

KARREN ALENIER: I’m used to being interrupted. I grew up in house of six children. I was eldest. The point is when I am working, I am able to ignore the lure of online wonders like YouTube, blogs and newspapers. However, I like to work in silence and know that listening to radio, TV, or music is too distracting. Yes, my smart phone is an interrupter. Still I don’t turn that off because someone important to me might reach out and need me. Some of my friends get annoyed that I don’t read their Facebook pages except occasionally. The best way for me to get something done is to put it on my list of things to do. I take great pleasure in ticking off those items.

C.M. MAYO: How has it been to read poetry on Zoom? Do you see the future all Zoom-y?

KARREN ALENIER: I have had numerous successful readings on Zoom. Check them out through my website at https://www.alenier.com/videos. I like the platform and I have been making opportunities for other poets through Zoom. Yes, of course, there is a future in online readings. You get a bigger more geographically diverse audience. It’s exhilarating.

C.M. MAYO: For those looking to publish a book of poetry, what would be your most hard-earned piece of advice?

KARREN ALENIER: If a publisher says s/he likes part of your manuscript, ask immediately if you can send a revision. Don’t delay by feeling sorry for yourself or thinking someone else might like the whole thing. Take your openings when they present.

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you as a poet?

KARREN ALENIER: I’m currently working on poems in response to Tender Buttons (Gertrude Stein) and I’m taking others along for the experience. I expect to announce the Tender Buttons anthology project in October 2021. The first of three books will be published by The Word Works in 2022.

C.M. MAYO: Can you share your most vivid memory of Paul Bowles?

KARREN ALENIER: In August 1982, I arrived for a writing appointment at his apartment door in Tangier wearing a djellaba over my clothes and purse to protect myself from pickpockets or other people interested in my things. I was hot and when invited in by Paul Bowles, I asked if he would mind if I took off my robe. He looked at me with surprise and said, “oh, I forgot my jacket.” He grabbed his jacket and put it on and then he said, “Of course, you may take your djellaba off.”

C.M. MAYO: Can you talk about your involvement with The Word Works?

KARREN ALENIER: I was the first poet published by The Word Works in 1975. The next year, I started workshopping poetry with other members of Word Works at the Joaquin Miller cabin in Washington, DC’s Rock Creek Park. By 1978, I started the Joaquin Miller Cabin Poetry Series which has been running every summer since then. In 1986, I became the second president and chairperson of the board of directors. In 1987, under my leadership, the Washington Prize moved from a single poem contest to a book prize with a cash purse. In 1989, I founded the Capital Collection imprint (now known as the Hilary Tham Capital Collection) which awards book publication to poets who volunteer for literary organizations like The Word Works. In 1999, I started the Café Muse Literary Salon at Strathmore Hall in Bethesda, Maryland. The series has been running monthly ever since with the excellent help of many volunteers. In 2009, Nancy White became the third president of Word Works. She leads the publishing and, while staying involved in the publishing, I spend more time on public programs. I have innovated many programs for The Word Works and pride myself on this strategy—I tell our volunteers I expect them to have fun and if they aren’t, they shouldn’t continue.

how we hold on

my mother kept a steamer trunk

with classic clothes immune to fad

my husband owned a cedar chest

packed with bits reins and riding whip

I am neither fashionista

nor ardent horse enthusiast

in my chest an aging heart brims

with blood both beautiful and swift

—Karren L. Alenier

when it drops you gonna feel it

we traded

Internet for mosquito

net cocooned

for sleep

under a halo

of white mesh

the sea beating

the coral cliffs

of Negril a lullaby

of dominoes geckos

the kingpins in the road

hawking anythingyouwant

the minstrel Fire improvising

Toots Hibbert’s “Pressure Drop”

a daughter hopeful that her father

in a Sav-la-Mar hospital would kick

lung cancer with an herbal medicine

something six chemo treatments

in Georgia couldn’t do

—Karren L. Alenier

Visit Karren Alenier’s website at www.alenier.com

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

Q & A with Diana Anhalt on Her Poetry Collection Walking Backward

Q & A: Joseph Hutchison, Poet Laureate of Colorado, on The World As Is

AWP 2019 (Think No One Is Reading Books and Litmags Anymore?)