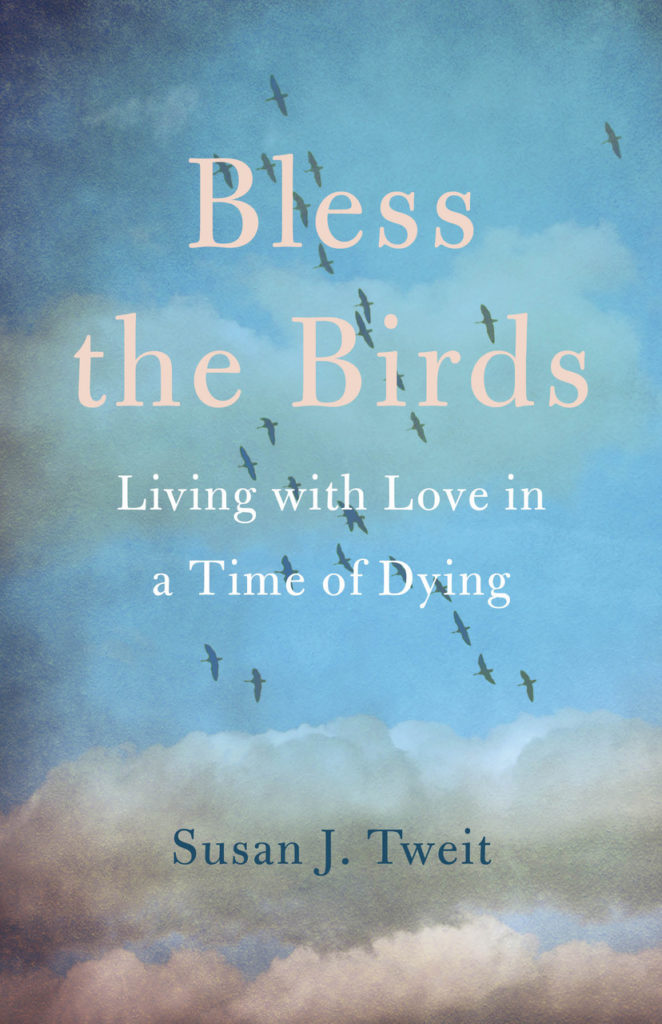

“My ideal reader is someone who recognizes that someone they love will die, and wonders how to make that journey with them in a way that is honest and open, supportive and loving.” —Susan J. Tweit

This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

My writing students have often asked me if I think it worth the time, expense, and trouble to attend a writer’s conference. The older I get the less certain I am about what would be best for other writers, but I can say that for me the writers conferences I’ve attended have all been well worthwhile, and for many reasons, one of the most important being the chance to meet other writers and become acquainted with their work. One of these wonderful writers, whom I met some years ago at Women Writing the West, is Susan J. Tweit. I relished her splendid essays about the Chihuahuan Desert collected in Barren, Wild and Worthless. Her new memoir, Bless the Birds: Living with Love in a Time of Dying, out this week from She Writes Press, promises to be a beautiful, mind- and heart-opening read.

Here’s the publisher’s catalog copy for Bless the Birds: Living with Love in a Time of Dying:

“Writer Susan Tweit and her economist-turned-sculptor husband Richard Cabe had just settled into their version of a “good life” when Richard saw thousands of birds one day―harbingers of the brain cancer that would kill him two years later. This compelling and intimate memoir chronicles their journey into the end of his life, framed by their final trip together, a 4,000-mile-long delayed honeymoon road trip.

“As Susan and Richard navigate the unfamiliar territory of brain cancer treatment and learn a whole new vocabulary―craniotomies, adjuvant chemotherapy, and brain geography―they also develop new routines for a mindful existence, relying on each other and their connection to nature, including the real birds Richard enjoys watching. Their determination to walk hand in hand, with open hearts, results in profound and difficult adjustments in their roles.

“Bless the Birds is not a sad story. It is both prayer and love song, a guide to how to thrive in a world where all we hold dear seems to be eroding, whether simple civility and respect, our health and safety, or the Earth itself. It’s an exploration of living with love in a time of dying―whether personal or global―with humor, unflinching courage, and grace. And it is an invitation to choose to live in light of what we love, rather than what we fear.”

C.M. MAYO: What inspired you to write Bless the Birds?

SUSAN J. TWEIT: The subtitle explains it: Living with Love in a Time of Dying. Bless the Birds is a love story about the journey my husband, Richard, and I took with his brain cancer. Those two-plus years of “bonus time” after he was diagnosed with terminal cancer were our time to live, laugh, love, create, rail at fate, grieve, and travel—literally and metaphorically—through the tierra incognita of life’s ending. I wrote the memoir with the idea that our journey could be useful to others.

What I find compelling about memoir is that it is a way to make use of my life experiences, “composting” them, as it were, into stories that inspire, inform, or guide others, whether or not they will ever encounter similar situations. At its best, memoir proves the truth of the saying, “The personal is the political.” Meaning how we live offers wisdom to illuminate national and world events, whether the generational trauma of racism, the struggle to live through the COVID-19 pandemic, or the long-term planetary crisis of climate change.

After this year of COVID-shutdown, with elders isolated in care homes and the acutely ill isolated in ICUs, we desperately need to return personal contact and loving care to life’s ending. And we must learn to accept normal death as a part of life, a turn in the cycle that carries us to whatever is beyond this world, and recycles the elements of what was “us” into other existences. Learning to embrace life’s ending in an open way frees us to live more fully in whatever time we have, to love more, and to be more compassionate citizens of this numinous blue planet.

C.M. MAYO: As you were writing, did you have in mind an ideal reader?

SUSAN J. TWEIT: Not really. When I write, I work first at finding the deepest parts of the story, and weaving a tight narrative. Then I think about who might read it.

C.M. MAYO: Now that it has been published, can you describe the ideal reader for this book as you see him or her now?

SUSAN J. TWEIT: My ideal reader is someone who recognizes that someone they love will die, and wonders how to make that journey with them in a way that is honest and open, supportive and loving. Not fearless, but without being paralyzed by fear. Perhaps they’re a caregiver for an aging parent, a friend who tends to the ailing, or simply a person of any age who wants to learn a healthier relationship with life’s ending time, what the German poet Rainier Maria Rilke called, “life’s other half.”

C.M. MAYO: Which writers have been the most important influences for you? And for Bless the Birds in particular?

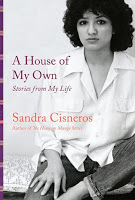

SUSAN J. TWEIT: I am drawn to writers who understand landscape and the other lives, human and moreso, we share this planet with, and how those relationships shape our humanity. Those writers include the late and much-missed Barry Lopez, plus Tempest Williams, Kathleen Dean Moore, Craig Childs, Louise Erdrich, Linda Hogan, Robert Michael Pyle, Denise Chávez, Anne Hillerman, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and Priscilla Stuckey.

C.M. MAYO: Which writers are you reading now?

SUSAN J. TWEIT: I am re-reading Barry Lopez’ Winter Count and other short stories for their magical realism, David Abrams (The Spell of the Sensuous), and Kati Standefer’s new memoir, Lightning Flowers.

C.M. MAYO: How has the Digital Revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

SUSAN J. TWEIT: When I am writing, I am in another world. I turn off notifications on my phone and computer, so that I’m not distracted by the bing of email coming in or the ding of texts or news alerts.

My daily routine is pretty simple: I post a haiku and photo on social media every morning (Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram), and answer any comments on my posts. After half an hour on social media—I set a timer—I read the news online. When I’ve finished with the news—which is research time for me, as news stories, especially those about science, are raw material for my writing—I write until the well runs dry. And then, usually at two or three in the afternoon, I allow myself to go back to social media, answer other comments, check the news. Then I close my laptop and go outside into the real world and walk for a mile or two on the trails around my neighborhood to clear my head. Getting outside into the “near-wild” of the greenbelt trails in my high-desert neighborhood keeps me sane in turbulent times, and refills my creative well. Nature is my medicine, inspiration, and my solace.

C.M. MAYO: Another question apropos of the Digital Revolution. At what point were you working on paper? Was working on paper necessary for you or problematic?

SUSAN J. TWEIT: I still work on paper. I write first on my laptop, and then when I’m ready to edit, I print a copy out, read it aloud, and edit as I go. The next round of editing is on screen, and then after that, I go back to paper and reading aloud, and so on. That way I “hear” my piece in different ways on the different media.

C.M. MAYO: For those looking to publish a memoir, what would be your most hard-earned piece of advice?

SUSAN J. TWEIT: In the writing stage, be honest. When you get to a scene or place or event you want to skip over, stop and ask yourself, what am I afraid of? And then go there. Find the universal threads in your personal story—memoir works when it reaches beyond the personal into the territory that anyone can learn from. And when looking for an agent or publisher, be perseverant. Memoir is a crowded field these days, and yours has to be the best it can possibly be to stand out, and it also has to be so compelling that an editor or agent simply cannot put it down.

C.M. MAYO: What important piece of advice would you give yourself if you could travel back in time ten years?

SUSAN J. TWEIT: Believe in yourself. Don’t compromise. You can survive this (Richard, my late husband, was beginning his journey with terminal brain cancer ten years ago).

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you as a writer?

SUSAN J. TWEIT: Right now, my writing is mostly answering interview questions related to Bless the Birds! When I have time for other work, I will start on the next book, which I call Sitting with Sagebrush. It’s a memoir about the native plants I have loved and worked with my whole life, and what these rooted, green beings can teach us about being human.

Visit Susan J. Tweit and learn more about her work at susanjtweit.com

Q & A with Sergio Troncoso, Author of

A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son

On the 15th Anniversary of Madam Mayo Blog

Biographers International Interview with C.M. Mayo:

Strange Spark of the Mexican Revolution

*

My new book is Meteor