This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

“I’ve always thought that the way poetry is taught often ruins it for young readers.“—Joseph Hutchison

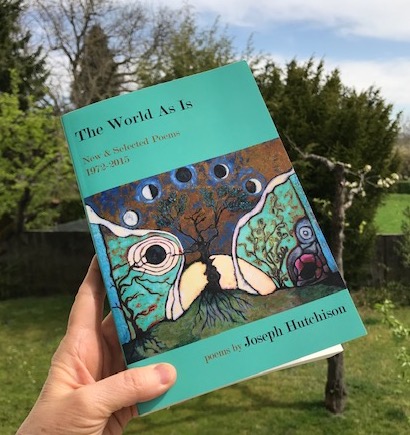

One of the blogs I’ve been following for a good long time is poet Joseph Hutchison’s The Perpetual Bird. We have never met in person but I feel as if we have; moreover, we have friends in common, among them, poet, essayist and translator Patricia Dubrava– and if my memory serves, it was her blog, Holding the Light, that first sent me to The Perpetual Bird. Here on my desk I have Hutchison’s collection of his works of several decades, The World As Is. From publisher NYQ Books’ catalog copy:

“In The World As Is Colorado Poet Laureate Joseph Hutchison gives voice to pain and passion, sorrow and joy, longing and exhalation. His poems seem to result from a wrestling with angels–the angels of transformation we all must confront to survive what Robert Penn Warren called ‘this century, and moment, of mania.'”

From The World As Is (originally in The Rain at Midnight), posted here by permission of the author.

THE BLUE

by Joseph Hutchison

In memory of Michael Nigg,

April 28, 1969 – September 8, 1995

The dream refused me his face.

There was only Mike, turned away;

damp tendrils of hair curled out

from under the ribbed, rolled

brim of a knit ski cap. He’s hiding

the wound, I thought, and my heart

shrank. Then Mike began to talk—

to me, it seemed, though gazing off

at a distant, sunstruck stand of aspen

that blazed against a ragged wall

of pines. His voice flowed like sweet

smoke, or amber Irish whiskey;

or better: a brook littered with colors

torn out of autumn. The syllables

swept by on the surface of his voice—

so many, so swift, I couldn’t catch

their meanings … yet struggled not

to interrupt, not to ask or plead—

as though distress would be exactly

the wrong emotion. Then a wind

gusted into the aspen grove, turned

its yellows to a blizzard of sparks.

When the first breath of it touched us,

Mike fell silent. Then he stood. I felt

the dream letting go, and called,

“Don’t!” Mike flung out his arms,

shouted an answer … and each word

shimmered like a hammered bell.

(Too soon the dream would take back

all but their resonance.) The wind

surged. Then Mike leaned into it,

slipped away like a wavering flame.

And all at once I noticed the sky:

its sheer, light-scoured immensity;

the lavish tenderness of its blue.

C.M. MAYO: You have been the Poet Laureate of Colorado from 2014. What does that mean, and what does that involve? (And how do you look back on that experience now?)

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: As I write this, I’m nearing the end of my Laureate term. It’s officially a 4-year term but mine was extended by a year to bring the selection of the next Laureate in line with Colorado’s political calendar. The PL is chosen by the Governor, and the organizations that administer the program—Colorado Humanities and Colorado Creative Industries—wanted to be sure the new Governor would have that opportunity.

Being selected was a great honor, of course, especially because it was John Hickenlooper who made the choice. He’s a real reader, an English major who started out with the aim of becoming a writer but decided early on that it wasn’t for him. Writing creatively, after all, is more of a calling than an occupation for most of us. If you’re not obsessed, what would be the point?

The best aspect of serving as the state Laureate has been traveling around the state and meeting lots of poets and poetry readers in communities large and small. I was born in Denver, which sits on the eastern plains at the foot of what we call “the Front Range”: 300 miles of the Rocky Mountains stretching from southeastern Wyoming to more-or-less the New Mexico border. Nearly the poets I knew coming up were in this region. So it’s been an exhilarating experience to find so many excellent poets within and on the western side of the Front Range. There is a poetic renaissance going on across Colorado, at the community level, and I’ve gotten to witness it close up. That’s been the main privilege.

I’ve also helped to shape the Poets section of the online Colorado Encyclopedia, which I’d never have been able to do without the PL cachet. The project is looking for more funding at the moment, but in the long run I’m sure it will serve as a resource for teachers around the state. I’ve always thought that the way poetry is taught often ruins it for young readers. It’s seldom taught the way fiction is taught—as a source of knowledge with deep roots in the human psyche; instead, it’s used as an instrument to teach about techniques: meter, rhyme, metaphor, symbolism … blah blah blah. No wonder so many people recoil from poetry once they’re out of school!

Anyway, I’m hoping the Encylopedia will help teachers connect with the poets in their own community and bring them and their work into their classes. I was 22 and in college before I saw a living poet—it happened to be Robert Bly; until then I’d been dabbling with poetry, but after that experience, after I witnessed what poetry could be, I was hooked. My fondest hope that my appearances around the state may have helped some fledgling poet discover that deeper commitment, and maybe encourage people in some community or other to honor that poet’s work when it surfaces in their midst.

C.M. MAYO: One of the things that struck me in your bio is that, although you teach in a university, you describe yourself as a community poet “using language that is at once direct and layered.” Can you talk a little about some of the poets you have taught and/or read who are not part of the academic world?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: A quick sketch of my writing life. I started writing poetry in high school, continued in college, went on to an MFA. After grad school I floundered—too credentialed to teach in Denver area public schools (teacher glut), under-credentialed to teach full time in a college (no yen for a PhD). Wanted to be a working writer but could write only poetry, which as everyone knows pays nada. Worked in a college bookstore for a several years, buying used text books and later university press and mass market paperbacks. Got invited to apply for a writing job in a bank marketing department (7 years), then a real estate network (3 years), then a software company (2 years), then went out on my own for 2 years, then created a “boutique” marketing company with my wife which sustained us, more or less, for 22 years. All along I was writing and publishing poetry, giving readings, conducting workshops—and teaching off and on as an adjunct. It was only in 2014, just after I had turned 64, that I entered the Academy full time to direct a program in which I had taught as an adjunct once or twice a year for more than a decade.

My point is that I never been an “academic” poet and never written what I think of as academic poetry. To be honest, I’m not sure what academic poetry is, though—like pornography—I feel like I know it when I see it! Essentially, I think of it as poetry written for graduate students, which speaks to the concerns of graduate students: their fascination with “schools” and the recondite reaches of aesthetic theory. In The Satire Lounge I wrote a poem lampooning this kind of stuff, and not just for fun.

The fact that the audience for poetry seems to be growing is a testament to the resurgence of poets who reach beyond schools and theories to address readers where they live. The poets of Merwin’s generation did this—think of Levertov and Rich, Kinnell and Wright and Bly*—and I think we’re seeing a return (with differences, of course) to this kind of poetry.

[*W.S. Merwin, Denise Levertov, Adrienne Rich, Galway Kinnell, … Wright, Robert Bly- C.M.]

I have so many poets in mind that it’s probably best just to list some of them, including a few from my own generation: Ted Kooser, Louise Glück, Kay Ryan, Li-Young Lee, Bill Knott, Yusef Komunyakaa, Mark Irwin, Jared Smith, Carl Phillips, Ada Limón, Terence Hayes, Wayne Miller, Ilya Kaminsky, Tracy K. Smith, Wendy Videlock, Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer….

This is kind of silly, now that I think of it. These are just some of my personal favorites. And who knows if they’d all get along if put in the same room together!

C.M. MAYO: How might you describe the ideal reader for your poems and, in particular, for your collection of new and selected poems 1972-2015, The World As Is?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: Someone capable of being moved emotionally and intellectually by language that aims to express those moments with the inner world and the outer world meet.

C.M. MAYO: Can you talk about which poets have been the most important influences for you as a poet and writer—and which ones you are reading now?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: Honestly, my earliest poetic influences were Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, and Joni Mitchell—I took up guitar but discovered I had little talent for it.

On the more formal side, I would have to say, in poetry and in no particular order: T. S. Eliot, Walt Whitman, William Blake, Robert Browning, Robert Bly, W. S. Merwin (both his own poems and his translations), Galway Kinnell, Denise Levertov, James Wright, Theodore Roethke, Rilke, Tranströmer, Neruda, Paz, Miłosz, Cavafy, Seferis, Zbigniew Herbert, Zagajewski, Szymborska.

In literature broadly speaking: Hemingway, Fowles, Márquez, Dürrenmatt, Cortázar (the short stories), Raymond Carver, Joseph Campbell, David Loy.

C.M. MAYO: What is the best, most important piece of advice you would give to a poet who is just starting to look to publish in magazines and perhaps publish a first book?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: Consider your own reading passions among your contemporaries and the generation just prior. Pick maybe 10 whose aesthetic ballpark you feel you’re playing in yourself. Then look at their Acknowledgments pages and see where they’ve published. Track down those publications and see if they make sense for you. Then submit.Submit over and over. When a batch of poems bounces back (this willhappen), read them over, make any changes that have become obvious in their time on the road, then send the batch out again. Do this over and over and journal publication will almost certainly come your way.

I have no good advice for book publication. I despise contests, though I’ve entered them a few times and had a manuscript picked up only once. My other books have come about via query letters or by invitation from a publisher who saw my work in a journal or anthology.

I do recommend that you create a blog. I believe I would never have become PL without The Perpetual Bird, the blog I started in 2008. Since becoming PL, I haven’t kept up with it the way I should, and it’s one of the things I look forward to getting back to!

From The World As Is (originally in House of Mirrors), posted here by permission of the author.

CITY LIMITS

by Joseph Hutchison

For Melody

You’re like wildwood at the edge of a city.

And I’m the city: steam, sirens, a jumble

of lit and unlit windows in the night.

You’re the land as it must have been

and will be—before me, after me.

It’s your natural openness

I want to enfold me. But then

you’d become city; or you’d hide

away your wildness to save it.

So I stay within limits—city limits,

heart limits. Although, under everything,

I have felt unlimited Earth Unlimited you

“I do recommend that you create a blog. I believe I would never have become PL [Poet Laureate] without The Perpetual Bird, the blog I started in 2008.”

C.M. MAYO: If a reader who knew nothing of your work were to read only one poem of yours, which would you suggest, and why?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: This is a tough one! I have personal favorites but have no idea what any given reader might think of them. Off the top of my head, I’d suggest “Touch,” from The World As Is. It’s a sestina, the only successful one I’ve ever written, and speaks on multiple levels to the political and cultural moment we’re in and have been in for a good two decades, if not longer. It’s one that audiences at readings always respond to, which is one indication that it may be worth reading on the page.

C.M. MAYO: You have been a consistently and remarkably productive poet and writer for many years. How has the Digital Revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: I wouldn’t say I’ve been consistently productive. I don’t have a writing routine, but when a poem does rear its Hyacinthine head, I become obsessive—preoccupied, distracted—and I pretty much stop answering emails. I have my blog set up so that my posts automatically flow through to a few social media sites, but I don’t generally visit those sites myself, even less so now that I’ve turned off notifications. Unfortunately, I follow numerous sites for political and poetical news, so that when a poem’s finished, I have to wade through days of unread articles. Overall, I’d say that I don’t feel much of a stake in social media, which is generally antisocial and trivializing. I don’t consider it a writerly medium.

“I don’t feel much of a stake in social media, which is generally antisocial and trivializing. I don’t consider it a writerly medium.”

From The World As Is (originally in The Earth-Boat), posted here by permission of the author.

GUANÁBANA

by Joseph Hutchison

After Hurricane Gilbert, this place

was only shredded jungle. Now

it’s Jesús and Lídia’s casa,

built by him, by hand, weekends

and vacations, the way my father

built our first house. Years

we’ve watched the house expand,

two rooms to three, to four, to five.

The yard, just a patch of gouged

sand and shattered palmettos once,

is covered now in trimmed grass,

bordered by blushing frangipani

and pepper plants—jalapeños,

habaneros—and this slender tree

Jesús planted three years back,

a stick with tentative leaves then

out of a Yuban coffee can, but now

thirty feet high, its branches laden

with guanábana—dark green

pear-shaped fruit with spiky skin

and snowy flesh, with seeds

like obsidian tears. Jesús

carves out a bite and offers it

on the flat of his big knife’s blade:

the texture’s melonish, the taste

wild and sweet—like the lives

we build after hurricanes.

C.M. MAYO: And another question apropos of the Digital Revolution. At what point, if any, were you working on paper? Was working on paper necessary for you, or problematic?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: I still work on paper. I write by hand, with different pens (ballpoint or felt tip, in various colors, depending on my mood), scribbling in notebooks—I sometimes have trouble reading my own writing—and get a poem pretty far along before I type it into Word; even then, I print out each draft and scribble in the margins, draw arrows, question marks, exclamation points, notes-to-self (“Look this up,” “Feels like a quote,” “Weak…,” “Expand…,” etc.): a physical dialogue with the page. I have tried off and on to write on screen but have never succeeded. I read every line aloud as I’m revising (I do this with most prose, too), which is why I end up revising in different locations: I move to wherever my muttering won’t bother my wife. So yes, paper is necessary. When I think of a great poet like A. R. Ammons composing on a typewriter, I confess to feeling baffled.

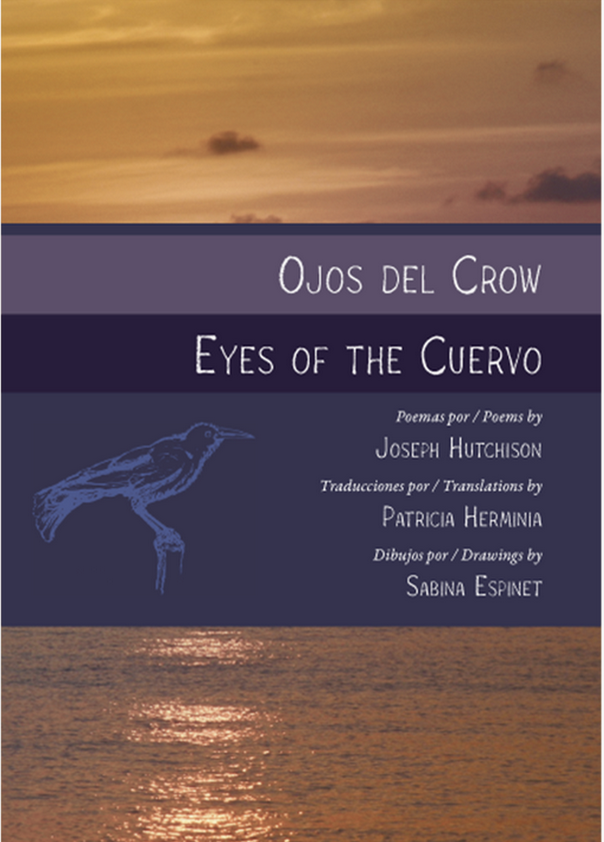

C.M. MAYO: You have recently brought out a very unusual book, the bilingual Ojos del Crow / Eyes of the Cuervo . Can you talk about this a bit, and what prompted you to write it?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: This is a bit of a long story.

To celebrate our first wedding anniversary, my wife Melody and I went to a beautiful, small seaside resort on the Caribbean coast of Yucatán called Capitán Lafitte, situated between Puerto Morelos and Playa del Carmen. We fell in love with it and started going back every year around our anniversary.

A few years into that routine, our business ran into some problems and we figured we’d have to forgo our annual trip. But Melody came up with the idea of doing a yoga retreat, which she called Yoga Fiesta. This venture essentially paid for our vacation.

When Capitán was severely damaged two years in a row, the owners sold the property, but one of them bought a less damaged hotel a couple of kilometers south, restored it, and opened up the following year as Petit Lafitte. All of our friends from Capitán came back to work at Petit, and Melody moved Yoga Fiesta there as well. (This April will be the 15thannual Yoga Fiesta!) Anyway, the two Lafittes have been inspirational for me, in terms of the natural beauty of that coast, the richness of Mayan culture, and the many friendships that we’ve enjoyed there.

Over the years, I’ve written many poems about the place and the people, and in 2012 a wonderful small press called Folded Word published a selection of these Mexico poems in a book called The Earth-Boat.

A few years later, Patricia Herminia, a former student and good friend of mine, who had been living in San Miguel de Allende and working as a professional translator, moved back to Colorado. She’d seen a copy of The Earth-Boat and wanted to translate the poems into Spanish. I revised a few of the poems and added a few more from my stash, then Patricia and I spent several months off and on bringing them over into Spanish. Another friend, the fine artist Sabina Espinet, provided some evocative illustrations, and Eyes of the Cuervo / Ojos del Crow was born. I consider it an homage to a region that is struggling to maintain its beauty and integrity against a tidal wave North American money.

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you as a poet and writer?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: Over the years, as I pulled together poems for various books, I often found that I had to set aside poems that felt worthy but just didn’t fit into the arc of a particular collection. So I’ve “rescued” some of those older poems and am working to see what kind of book they make. So far, so good.

I’m also working on adapting some of my teaching materials into a small book on writing poetry. It’s always seemed to me that we try to use the vocabulary of criticism to talk about the creative process, but the terms are inadequate. Critics analyze (from the Greek root meaning “a breaking up, a loosening, releasing”), while poets synthesize (from the Greek root meaning “put together, combine”). These processes are opposed to one another, and it makes no sense to me that we should approach the creative process using the tools and concepts of criticism. On the other hand, who needs another book of this kind?

*

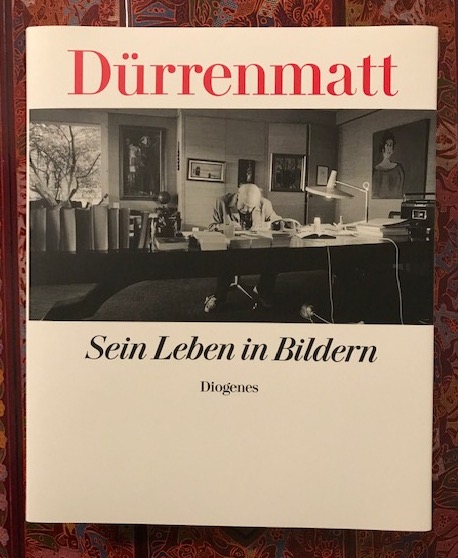

C.M. MAYO: I recently posted on a visit to the home/ museum of Swiss German writer Friedrich Dürrenmatt [the post is here; scroll down to the end for the part about Dürrenmatt], which was prompted by Hutchison’s recommendation, so I asked him:

Which one of Dürrenmatt’s works would you recommend an English-language reader to start with?

JOSEPH HUTCHISON: I suggest The Judge and His Hangman and Suspicion, which are published together as The Inspector Barlach Mysteries. Dürrenmatt’s novels are addictive, frightening and comic by turns, as are his plays. His essays on art, literature, philosophy, politics, and the theater make exhilarating reading, too!

Q & A: David A. Taylor on Cork Wars: Intrigue and Industry in World War II

Q & A: Roger Greenwald on Translating Tarjei Vesaas’s Through Naked Branches and on Writing and OPublishing in the Digital Revolution

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.