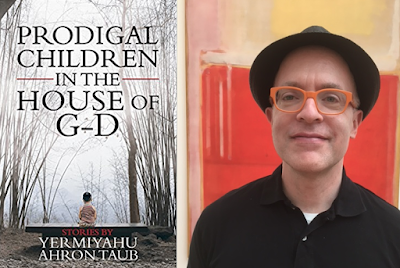

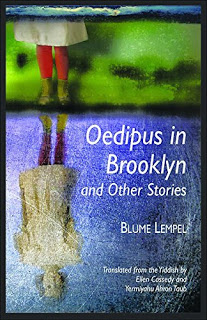

Starting this year, every fourth Monday I run a Q & A with a fellow writer. This fourth Monday features Yermiyahu Ahron Taub, the author of Prodigal Children in the House of G-d: Stories (2018) and six books of poetry, including A Mouse Among Tottering Skyscrapers: Selected Yiddish Poems (2017). Preparing to Dance: New Yiddish Songs, a CD of nine of his Yiddish poems set to music by Michał Gorczyński, was released in 2014. Taub was honored by the Museum of Jewish Heritage as one of New York’s best emerging Jewish artists and has been nominated four times for a Pushcart Prize and twice for a Best of the Net award. With Ellen Cassedy, he is the recipient of the 2012 Yiddish Book Center Translation Prize for Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories by Blume Lempel (2016). His short stories have appeared in such publications as Hamilton Stone Review, Jewish Fiction .net, The Jewish Literary Journal, Jewrotica, Penshaft: New Yiddish Writing, and Second Hand Stories Podcast.

C.M. MAYO: You are co-translator (with Ellen Cassedy) from the Yiddish of Blume Lempel’s extraordinary short stories, Oedipus in Brooklyn. Would you say that Lempel’s work has been an influence on your own fiction? Can you talk a bit about some of your influences, and your favorite writers?

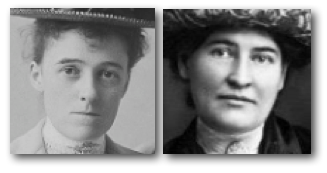

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: Blume Lempel is certainly a source of personal inspiration, and working with Ellen Cassedy on that project was and continues to be a great joy. Despite suffering enormous familial loss in the Holocaust and years of creative block, Lempel built a career as a Yiddish writer with single-minded focus and commitment. She created an authorial voice that was uniquely her own and a prose rich in poetry, experimentation in time and voice, and empathy. She looked at characters at the margins of society and at themes still considered taboo, including abortion, prostitution, and incest. I was drawn to Lempel’s work for all of these reasons and in researching her autobiography, came to be inspired also by the example of her courage in life and art. Our work overlaps somewhat in our interest in life at the margins and blurring the line between poetry and prose, although I think much of Lempel’s work is more firmly anchored than mine in the realm of the experimental and avant-garde. I do see Lempel as a kindred literary spirit.

I have been reading voraciously and widely since childhood. It’s difficult to pinpoint specific literary influences. I prefer to think of texts whose effects remain with me. Even if I don’t recall particular plots, the authors’ themes and concerns, and overall sensibilities remain. I am interested in writers who take risks, who go against the grain, who can create a marriage of emotional impact and beauty of language, who write with psychological acuity and care.

A partial list of favorite English-language fictional texts, in alphabetical order of author’s last name, include:

Julia Alvarez, How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents

Michelle Cliff, Abeng

Marian Engel, Bear

Janet Hobhouse, The Furies

F.M. Mayor, The Rector’s Daughter

Elizabeth McCracken, The Giant’s House: a Romance

Gloria Naylor, The Women of Brewster Place

Joyce Carol Oates, Where is Here?

James Purdy, 69: Dream Palace and Other Stories

Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea

Marilynne Robinson, Gilead, Home, and Lila

Sinclair Ross, As For Me and My House

Elizabeth Taylor, Angel and Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont

Edith Wharton, The House of Mirth

If we include non-fiction, poetry, and Yiddish literature and world literature in translation, there would be many more titles to add.

C.M. MAYO: You have been a consistently productive writer and poet for many years. How has the digital revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, Facebook, Twitter, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: The digital revolution has helped bring about a dynamic international literary culture. Poems and stories can now be read by anyone with computer access. Blogs such as yours also support the work of writers and connect writers and readers. Before appearing in book form, much of my work has appeared in online publications. In the digital age, it is more affordable to publish literary ‘zines, although maintaining the availability of defunct journals remains an issue of concern for literary publishers, writers, and readers. Facebook is useful for sending out announcements of new work and seeing what colleagues and friends have been doing. I also enjoy the travel, food, and family photos that people post! I started on Facebook fairly recently. I thought it would take more of my time that it actually has. I am not on Twitter or other social media.

There’s only a limited amount of time in the day. I like to set aside time for daily translation, reading, and/or writing or writing-related business, as well. The proliferation of media in the digital age offers tempting distractions from writing. There are now so many offerings in television and film, many of them quite literary and demanding extensive viewing time.

Still, I always return to the written word. And I prefer to read in hard copy. Nothing has replaced words on a paper—the joy that comes from concentration on those words, turning the page, the touch of paper, the heft of a book in one’s hand or one’s lap. The poems “Eavesdropping” and “Luddite’s Exhortation” in my fourth collection Prayers of a Heretic explore the pleasures—cerebral, sensual, and otherwise—of books and reading from books. The key to productivity is tuning out all of the distractions to draw on the creativity that emerges from focus and quiet, or perhaps more aptly put, quietude. One can be sitting in a noisy cafe and still be in a place of internal quiet.

But, of course, there are many ways to live and work as a writer. Find what works for you and honor that process.

C.M. MAYO: Are you in a writing group? If so, can you talk about the members, the process, and the value for you?

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: When I lived in New York, I was in the Yugntruf Yiddish writers’ circle for many years. Attendees brought in a poem or a story and shared it with the group. It was a great way for me to get feedback on my Yiddish writing and to encounter new Yiddish creativity. That group continues to meet. I have attended two sessions of a poetry group here in Washington, D.C. I’m not sure if that qualifies as being “in a writing group.” Here too, folks distribute the poems, read it aloud, and then provide comments. The feedback was quite rigorous and helpful, and I enjoyed the gatherings. However, I’ve only attended two sessions since my recent focus has been on writing prose and on translating from the Yiddish.

C.M. MAYO: Did you experience any blocks while writing these stories, and if so, how did you break through them?

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: Fortunately, I did not experience writer’s block while writing these stories. As I note in the book, I wrote Prodigal Children in the House of G-d while on an artist’s residency at The Writers’ Colony at Dairy Hollow (Eureka Springs, Arkansas). Having three weeks to concentrate solely on writing enabled my turn from poetry to fiction. TWCDH was a magical experience — a great studio, friendly staff and writers in residence, and the ideal setting that combined natural beauty and a charming, historical small town. During the afternoons, I took walks and worked through ideas for the writing I was doing in the studio. Sometimes, I took walks with other writers in residence.

C.M. MAYO: Back to a digital question At what point, if any, were you working on paper for these stories? Was working on paper necessary for you, or problematic?

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: My writing life as an adult has largely been conducted on the computer. Of course, the digital revolution has made it easier to submit work to literary magazines. Instead of having to print out hard copies, write and include a self-addressed stamped envelope, and go to the mailbox or post office, one can now submit work electronically. Writing on the computer also allows for extensive revision. In my childhood and youth, I wrote by hand. In college, I sometimes submitted papers typed on a typewriter. So I remember well the challenges in the revision process back then.

C.M. MAYO: Do you keep in active touch with your readers? If so, do you prefer hearing from them by email, sending a newsletter, a conversation via social media, some combination, or snail mail?

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: I welcome feedback from readers. I prefer e-mail over other forms of communication. I sometimes go for long periods of time without checking Facebook. I rarely use snail mail. I try to answer all letters. Giving readings, particularly ones that include a Q & A, is another great way to connect with readers.

COMMENT:

M.L. recommends checking out Yermihayu Ahron Taub’s page on Beltway Quarterly.

Q & A: Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub on Translating Blue Lempel’s Oedipus in Brooklyn from the Yiddish

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.