This blog posts on Mondays. Second Mondays of the month I devote to my writing workshop students and anyone else interested in creative writing. Welcome!

> For the archive of workshop posts click here.

SMOMBIE: It’s a word that popped up in Germany only in 2015. It’s hard to imagine now, but a decade ago, a scene, typical today, of smombies shuffling along city streets would have been but a cliché in a sci fi novel. But here we are.

When we lack the words to precisely describe something, it becomes difficult to recognize it, never mind debate and discuss it. Albeit some decades ago, the Digital Revolution burst upon us all, a series of tsunamis of such dizzying celerity that our vocabulary is still catching up. Only a few years ago a much-needed term was coined by Jake Knapp: “Distraction Free iPhone.” I came across the term when I read Knapp’s recent update on his experience here.

DISTRACTION FREE SMARTPHONE = DFS = defis

I’ll switch that last word from “iPhone” to “smartphone” to make it Distraction Free Smartphone, DFS for short. I did not think of my smartphone as distraction free until now, but for the past several years, that’s precisely what I have been moving towards, a DFS. Hmm, that sounds a mite snappier!

And I hereby tweak DFS to “defis,” which, I note, is the plural of “defi” which means “challenge” or “defiance.” Indeed, using a distraction-free smartphone is an act of defiance towards smombiedom.

BEYOND PRO OR CON

The magic is, this new word, DFS, or defis, nudges us beyond the rigid ping-pong of pro or anti-smartphone; forward-looking or old fogey. As I wrote in a recent post:

“The reigning paradigm is the same one we’ve had since forever: if it’s digital and new it must be better; those who resist are old fogeys. It’s a crude paradigm, a cultural fiction. And it has lasted so long a time in part because those who resisted either were old fogeys and/or for the most part could not articulate their objections beyond a vaguely whiney, ‘I don’t like it.’

“As an early adopter of digital technologies for decades now (wordprocessing in 1987, email in 1996, website 1998, blog 2006, podcast and Youtube channel 2009, bought a first generation iPad, Twitter 2008, and first generation Kindle, self-pubbed Kindles in 2010, etc.), I have more than earned the cred to say, no, my little grasshoppers, no, if it is digital and it is new it might, actually, maybe, in many instances, be very bad for you.

“In other words, adopting a given digital technology does not necessarily equate with ‘onwards and upwards’; neither does rejecting a given digital technology necessarily equate with backwardness. I so often hear that ‘there is no choice.’ There is in fact a splendiferous array of choices, and each with a cascade of consequences. But we have to have our eyes, ears, and minds open enough to perceive these, and the courage to act accordingly.”

Of course, when it comes to using digital technologies, different people have different needs, different talents, goals, obligations, opportunities, and vulnerabilities. A responsible mother with young children will probably want to use Whatsapp with the babysitter; a real estate agent who wants to stay in business needs to be available to clients, whether by phone, email or text– and so on. Some people slip into the vortex of addiction to social media or gaming far more easily than others…

My aim here is not to judge other people (although I’ll admit to some eye-rolling at smombies slapping themselves into streetlamps), but to examine the nature of digital technology and my own use of it. I am not a mother with young children, nor a real estate agent. Games bore me, always have. I am a writer of books. I blog about digital technology because first, it’s my way of grokking it; and second, I trust that what I’ve learned may be of interest to my readers– for I know that many of you are also writers.

We writers are hardly alone in the need for uninterrupted chunks of time. Brain surgeons, composers, painters, historians, statisticians, sculptors, software engineers… many people, in a wide variety of professions and vocations need, to quote Cal Newport, “the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task,” that is to say, engage in what he terms “deep work.”

“DEEP WORK”

Writing a book is deep work. And literary travel writing is especially demanding deep work. From my 2009 post on the nature of the genre:

“Literary travel writing is about first perceiving in wider and sharper focus than normal; then, in the act of composition, shaping and exploring these perceptions so that, as with fiction, it may evoke in a reader’s mind emotions, thoughts, and pictures. It’s not meant to be practical, to serve up, say, the top ten deals on rental cars, or a low-down on the newest ‘hot spas.’ Literary travel writing, at its best, provides the reader the sense of actually traveling with the writer, so that she smells the tortillas heating on the comal, tastes the almond-laced hot chocolate, sees the lights in the distant houses brightening yellow in the twilight, and, after the put-put of a motorcycle, that sudden swirl of dust over the road.”

Writers have always battled distractions, but with the ubiquity of smartphones, and increasingly sophisticated app designs and algorithms to lure us and trap us into “the machine zone,” we’re at a new level of the game– or the war, as Steven Pressfield would have it.

Whatever might or might not be an optimal use of digital technology for you, I know this:

A book that can claim a thoughtful person’s time and attention is not going to be written by someone who is pinged by & poking at their smartphone all the live-long day.

“OUT IN THE WORLD”

Some writers have outright rejected smartphones– but so few, in fact, that only two come to mind: John Michael Greer, a prolific blogger and author whose stance on modern conveniences is, as he titled a collection of essays on his vision of the post-industrial future, Collapse Now and Avoid the Rush; and journalist Sebastian Junger. As Junger said on the Joe Rogan podcast:

“when I’m out, I want to be out in the world. If you’re looking at your phone, you’re not in the world… I just look around at this– and I’m an anthropologist, and I’m interested in human behavior– and I look at the behavior, like literally, the physical behavior of people with smartphones and… it looks anti-social and unhappy and anxious, and I don’t want to look like that, and I don’t want to feel like how I think those people feel.”

While I say a quadruple “AMEN” to Junger’s comment, I decided to keep my smartphone because I value having the emergency information-access and communication backups enough to pay for the smartphone for that alone; plus, I much prefer using the smartphone’s camera and dictation app to having to carry separate appliances, and I use these often in my work.

For me, the question was never whether or not a smartphone is useful. For me, obviously it is. The question is rather:

How can I maximize the benefits of this sleekly convenient multi-tool / communications device, while blocking its djinn-like demands, and so with sharpest powers of observation and consciously directed concentration, stay awake in this world?

I had answered this question by turning my smartphone into a distraction free smartphone, as I realized when I read Jake Knapp’s post.

Knapp’s version of “distraction free” turned out to be different than mine– he deleted his smartphone’s Mail and browser apps, which I kept. And when I Googled around a bit to find other writers who had tried to convert their smartphone to distraction free– and they were astonishingly few– I found that each had a different version of distraction free. Some recommended using grayscale, which I did not find helpful– but you might. Again, no surprise, what works for one writer may not work for another.

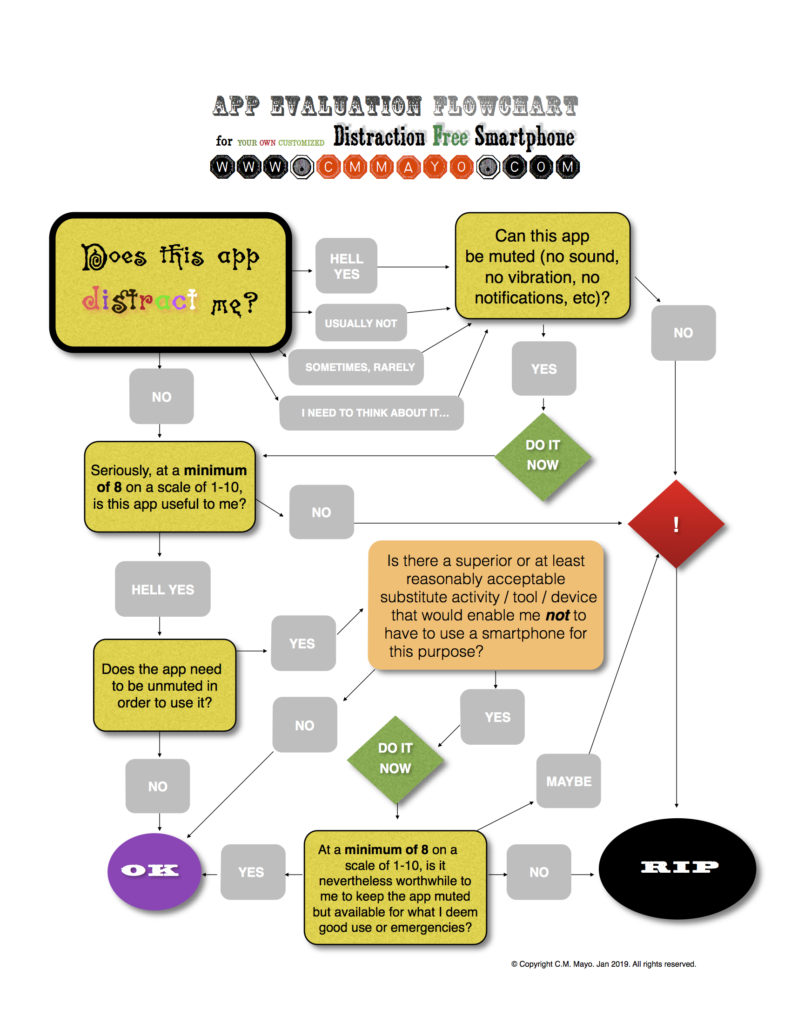

And that got me noodling… over the year-end holidays, instead of going to the movies, I stayed home and made my App Evaluation Flowchart for a Custom Distraction Free Smartphone, which you will find at the end of this post.

THIS WRITER’S DISTRACTION FREE SMARTPHONE (DFS or “defis”)

In early 2019, here’s where I stand, comfortable at last, with my smartphone. My defis, as it were. In order of importance, I use my smartphone as / for a:

Camera

(for stills and video)

Audioplayer

(various apps for audio books, podcasts, and music,

which I usually listen to when flying or driving,

never when walking or on public transport)

Emergency Mail

Recorder (dictation app for interviews)

Google translator

Emergency telephone

Emergency Google Maps

Emergency Safari

Calculator

Flashlight

In essence, I use my smartphone only when I decide it will serve me for a specific purpose, e.g., to take a photo, make a call, record an interview. Otherwise, it stays in the charging station at home or zipped into its felt bag in my backpack, wifi off, roaming off. I do not allow it to beep, rill, cheep, chirp, ding, ping or vibrate.

Other than the above-mentioned apps, I have deleted all apps (except the ones Apple will not allow me to delete; those I corralled into a folder I labeled “NOPE.” Do not ask me what they are, I do not remember.)

No social media apps, no Whatsapp, no news, no games.

All– all– notifications are off.

About the smartphone as a phone: I make a call from the smartphone maybe two or three times a month. I never check voicemail. Ever. I don’t know how to check voicemail and don’t tell me its easy because I don’t want to know how.

Text messages? Not my circus, not even my planet.

[UPDATE: See This Writers Distraction Free Smartphone: First Quarter Update, April 8, 2019]

If you leap to conclude that I’m living the life of a Luddite you’d be wrong. I do make and receive plenty of phone calls– except for emergencies, on a landline. I Skype. I spend hours galore on email– but at my desk, on a laptop. On the laptop I also manage my website and blog. I podcast, too, editing the audio with GarageBand (listen in anytime here). And I film and edit short videos for my YouTube and Vimeo channels.

When I first got an iPhone nearly a decade ago, oh, did I fiddle with apps, apps for this and apps for that and apps that would confect a fairy’s hat! I was becharmed by apps! Ingenious things, apps are.

I was on FB, too, until 2015.

But I am a writer of books, and this smartphone rabbit-hole-orama, it wasn’t working for me.

THE TWO MAIN PULLS

For me, the two main pulls to pick up the smartphone have been:

(1) to see any messages from people and/or about matters I care about;

(2) to have something convenient to read / look at when I’m away from my desk and feel bored.

Once I had this clear, I could formulate a more effective strategy than vaguely “finding a healthy balance” or blanging down the anvil of will power.

Over the past several years, trying to figure this out, backsliding, and trying again (and again) to figure this out, what I have found actually works is to remove or minimize temptations to even look at, never mind pick up, the smartphone when it is not in my fully conscious and decided interest to do so; and crucially, I have replaced those “pulls” to look at the smartphone with what are, for me, either superior or at least realistically acceptable alternatives.

B.J. FOGG

B.J. Fogg of Stanford University’s Behavior Design Lab has been an influence in my thinking about the smartphone. His basic equation for inducing a behavior is Motivation + Ability + Prompt (all three simultaneous), or B = MAP.

You can read more about Fogg’s behavior model here.

He’s all very sunny and even uses puppets when talking about his behavior model and how it can help people improve their lives, and I for one sincerely appreciate this. But I suspect that people with darker designs (oh I dunno, like those starry eyed newbies with VC in Silicon Valley who would launch a platform / app that, with maximum speed and efficiency, sucks the life-hours, money, and data out of you) also look to professor Fogg as a guru.

What I’m saying is, more likely than not, you are being very, very cannily manipulated by any one of a number of apps to pick up and remain focused on your smartphone despite what you know perfectly well are your better interests.

And understanding the way in is to understand the way out.

THIS WRITER’S STRATEGIES

I don’t pretend that my strategies will work for other writers. This section is not meant to be a series of recommendations but an example: what works for me, a working writer. (If you want to go direct to the App Evaluation Flowchart for a Custom Distraction Free Smartphone, just scroll on down to the bottom of this post.)

(1) Focus digital communications on email, and always at the desk, on the laptop

This is, to-the-moon-and-back, the most powerful strategy for me. (Read about my game-changing 10-point email protocol here.) I take email very seriously. However, with rare, emergency-level exceptions, I check email only on my laptop, only after 3 PM, and I batch it. I thereby establish the boundaries I need to be able to do my work, and I can truthfully say, “I welcome email,” and “the best way to reach me is by email.” And if not perfect, I am ever better about responding to email in a timely manner– since I have relatively fewer distractions!

Many people have told me that they would prefer to communicate with me on FB or Whatsapp, but… too bad! I am a writer who writes books, which means that I need to funnel communication into specific times, not allowing interruptions to leech my attention willynilly throughout the day. If someone cannot summon the empathy to appreciate that, well, like I said. (Anyway, I love you guys.)

This strategy allows me to keep the smartphone silent and in the closet (its charging station) or zipped in its bag inside my backpack. In B.J. Fogg’s terminology, I have hereby eliminated the motivation, the ability, and the prompts to pick up the smartphone. So I don’t.

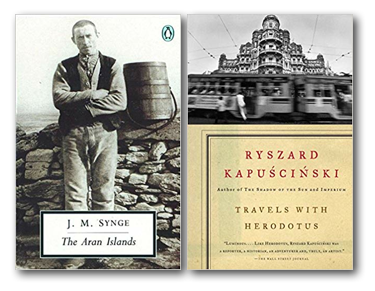

(2) When out and about, if there’s a chance of having to wait a spell, carry a paperback

J.M. Synge’s The Aran Islands

Ye, verily, of the time before Instagram

and TripAdvisor

(A classic of travel writing

and the Irish Renaissance,

and a reading cure for “the shallows”)

weighing in at about the same as a potato

This is the second most powerful strategy for me, and simple and old-fashioned as it is, it took what seems to me now an embarrassingly long time to figure it out.

I’ve always been an avid reader of books and magazines, but when I got an iPhone, suddenly, in spare moments, such as waiting at the dentist, in line at the grocery store, waiting for a friend in a coffee shop, I found myself pecking at it. I was reading, but… it was, in fact, more often skimming, watching, and surfing.

As Nicholas Carr explains in The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, reading a book and clicking & scrolling on a smartphone (from, say, website to website, to Twitter to FB to Whatsapp to YouTube to Instagram feeds x, then y, then z), do two very different things to one’s brain. The latter literally retrains your brain, resulting in what Carr calls “the shallows,” and once you’re in the shallows, tasks requiring sustained cognitive focus– such as writing a book– become ants-in-the-pants-nigh-impossible.

Don’t tell me I could use a Kindle app to read ebooks on my smartphone; I don’t and I won’t because, again, my goal is to remove as many siren calls to the smartphone as possible, relying on acceptable or superior alternatives. For me, a paperback provides a superior reading experience to an ebook; and if it’s not too heavy, I don’t mind tucking a real book in my bag.

But, by the way, I do read Kindles on occasion, using the Kindle app on my iPad, as a last resort only, when a paper copy is unavailable. I also use my iPad for reading news (which I inevitably regret), a select few favorite blogs, and for listening to audiobooks and podcasts in the kitchen. (If not in its charging station, or with me as I am doing something like say, folding laundry, my iPad remains parked on the kitchen counter.)

In B.J. Fogg’s terminology, with this strategy, I have reduced the motivation to pick up the smartphone. Also in his terminology, I build a tiny habit: when tempted to take out the smartphone to surf, take out the paperback. (You can watch Fogg’s TEDx talk on tiny habits here.)

(3) For a calendar, “to do” lists, and selected contacts, use a Filofax

This strategy is an old one for me, tried and true. As Getting Things Done guru David Allen says, “low-tech is oftentimes better because it is in your face.” The Filofax is a century-old British system designed for engineers that is so efficient it still has legions of devotees, among them myself, for over 30 years now. My lovely and ridiculously sturdy cherry-red leather Filofax normally stays next to my laptop on my desk; I can, but I rarely carry it with me.

As for contacts, I keep the addresses and telephone numbers I need at-hand in the Filofax and the rest in a separate system, but not on the smartphone because, again, I aim to focus my communications on email, and always on the laptop. (My smartphone does have emergency contacts.)

> Read my post about the Filofax for Kevin Kelly’s Cool Tools blog.

In B.J. Foggese: For my to dos and calendar, I have no motivation nor prompts to pick up the smartphone.

(4) For an alarm clock use an alarm clock (and for a watch use a watch)

Back in the days of my starry-eyed wonderfest with apps, I downloaded three different alarm clock apps. The cornucopia of “alarms,” from harps to waterfalls to drums to roosters yodeling, that was fun. But I deleted them all and instead use a little plastic alarm clock powered by two AA batteries. It weighs almost nothing, cost less than ten bucks, and works just fine– so I can keep the volume on the smartphone on mute. Don’t tell me I could adjust the volume on the alarm clock app because I don’t want to touch the smartphone if I don’t have to, and certainly not as the last thing at night and first thing in the morning. And I don’t want the smartphone parked anywhere near where I sleep.

This strategy might sound silly. How is the alarm clock app different than say, the calculator or the flashlight or the camera or diction app? The answer is, by definition an alarm clock distracts, it prompts me to pick it up to turn it off– and that is precisely what I do not want my distraction free smartphone to do.

This is not trivial.

In B.J. Foggese: another motivation, ability, and prompt to pick up the smartphone eliminated.

(5) Use paper maps

You read that right. People laugh at me. I laugh back! Sometimes I use a store-bought map but more often, before I go out, I’ve Googled on my laptop and printed out or sketched the directions. I do make use of Google Maps on the laptop and on my smartphone in emergencies– this is one of the reasons for which I keep a smartphone. But by relying primarily on paper, rather than GPS via the smartphone in realtime, I have removed yet another reason to pick up and start poking at the smartphone.

An added benefit, crucial for me as a travel writer, is that my sense of space, direction, and the lay of any given landscape have remained sharper.

(If you love the planet and believe everything paper should be digital, I would invite you to Google a bit to learn about the energy realities of server farms and what precisely goes into smartphone batteries.)

(6) Always carry a pen and small a notebook

Another opportunity to not pick up the smartphone.

(7) Make it a habit to keep the smartphone zipped inside its bag

I don’t make a habit of holding my smartphone in my hand, carrying it in a back pocket, or setting it down on the desk or table next to me. Unless it’s an emergency, or I have an excellent, fully conscious reason to take it out and use it, the smartphone stays dead quiet and out of sight in its bag inside the bag.

In B.J. Foggese, I thereby reduce my motivation, ability, and prompts to touch it.

IN CONCLUSION

My smartphone is now simply (albeit miraculously!!) a lightweight selected multi-tool (camera / recorder / audio player / caculator / flashlight) and emergency information-access and communications device which I carry when I go out of the house, unless it is to walk the dogs. (I never take it when I walk the dogs because when I walk the dogs, I walk the dogs.)

My smartphone does have Mail, Safari, and Googlemaps buttons, but because I rely on my laptop for email and other Internet access, and paper for out-and-about navigation, I no longer feel that pesky tug to pick up and peck at the smartphone– but I do have these apps available to me should I need them. And sometimes I do need them.

Ditto the telephone.

Again, and of course, what works for me may not necessarily work for you. But may this new term, Distraction Free Smartphone, or as I would suggest, DFS, or defis, serve you in thinking through your own concerns and strategies for your own smartphone and your own writing.

DFS MODE

I’ll add one more term: “DFS mode.” A smartphone need not be distraction free almost all the time, as mine is. Let’s say one needs to be available on Whatsapp, voicemail, email or to use some other app for family or work that may ping, ring or ding-ding you at random intervals, and so be it; then, for the time alloted for writing (or other deep work), one’s smartphone could be put into DFS mode. As I hope I have made abundantly clear, this would not necessarily be the same as “airplane mode.”

P.S. Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World will be out next month. From what I’ve read of his other books and blog, this promises to be a pathbreaking book. If nothing else, the term “digital minimalism” adds depth and nuance to our thinking about digital technology and our use of it.

[UPDATE: This Writers Distraction Free Smartphone: First Quarter Udate, April 8, 2019.]

App Evaluation Flowchart for your Own Customized Distraction Free Smartphone

# # # # #

> Your comments are always welcome. Write to me here.

Q & A: Sara Mansfield Taber on Chance Particulars: A Writer’s Field Notebook

Email Ninjerie in the Theater of Space-Time

30 Deadly-Effective Ways to Free Up Bits, Drips & Gimungously Vast Swaths of Time for Writing: A Menu of Possibilities to Consider

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.