“what I love and crave about writing fiction is that it’s a process that feels timeless and part of my essential self.”

– Joanna Hershon

This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

Widely-lauded novelist Joanna Hershon’s latest, which is scheduled to launch this April from Farrar, Straus & Giroux– just when the brick-and-mortar bookstores will be reopening, one hopes!–promises to be an all-star book club pick. Here’s the catalog copy:

Over the course of a weekend, two couples reckon with the long-hidden secrets that have shaped their families, in a charged, poignant novel of motherhood and friendship.

It’s the end of summer when we meet Sarah, the end of summer and the middle of her life, the middle of her career (she hopes it’s not the end), the middle of her marriage (recently repaired). And despite the years that have passed since she last saw her daughter, she is still very much in the middle of figuring out what happened to Leda, what role she played, and how she will let that loss affect the rest of her life.

Enter a mysterious stranger on a train, an older man taking the subway to Brooklyn who sees right into her. Then a mugging, her phone stolen, and with it any last connection to Leda. And then an invitation, friends from the past and a weekend in the country with their new, unexpected baby.

Over the course of three hot September days, the two couples try to reconnect. Events that have been set in motion, circumstances and feelings kept hidden, rise to the surface, forcing each to ask not just how they ended up where they are, but how they ended up who they are.

Unwinding like a suspense novel, Joanna Hershon’s St. Ivo is a powerful investigation into the meaning of choice and family, whether we ever know the people closest to us, and how, when someone goes missing from our lives, we can ever let them go.

Buy the book from all the usual online booksellers, including amazon and your local independent bookstore via indiebound.org

Read more about St. Ivo at joannahershon.com

C.M. MAYO: What inspired you to write St. Ivo?

JOANNA HERSHON: The original inspiration was something I experienced on the subway in NYC, where I live. A man began talking to me and something about the conversation was strange and felt almost other-worldly. Another inspiration was a conversation with my husband, who observed that what I was actually interested in was not a more straightforward thriller (which I had originally thought I’d wanted to write) and more along the lines of what he observed I was good at, which is creating suspense and human drama out of tense but ordinary situations.

C.M. MAYO: As you were writing St. Ivo did you have in mind an ideal reader?

JOANNA HERSHON: I have to admit that I never think that way, though I do feel in conversation with forces outside of myself. I think the ideal reader is someone who really engages with a book. Reading is such a private experience, and one can never predict what a reader’s experience will be. I love the mystery of this notion.

C.M. MAYO: And can you describe the ideal reader for St. Ivo as you see him or her now?

JOANNA HERSHON: I think my ideal reader is anyone—male or female—who is interested in relationships, who has loved deeply, who has an interest in platonic, parental and/or romantic love.

C.M. MAYO: Can you talk about which writers have been the most important influences for you?

JOANNA HERSHON: Different writers have come into my life and different moments. Off the top of my head and in no particular order: Leo Tolstoy, Phillip Roth, Michael Cunningham, Grace Paley, Helen Schulman, Jennifer Egan, Susanna Moore, Mona Simpson, Evan S. Connell, Scott Spencer, Wallace Stegner.

C.M. MAYO: Which writers are you reading now?

JOANNA HERSHON: I’m responding to this in the midst of the Corona virus, when I am especially atuned to books which—like mine—are being affected by this awful time. Phyllis Grant’s unique and gorgeous memoir Everything is Under Control is a gem of a book with excellent recipes. Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings is a book of sharp and powerful essays reflecting on the Asian American experience.

C.M. MAYO: How has the Digital Revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

JOANNA HERSHON: I imagine that, like most people, I’m more distracted with social media, texting and email but I still do feel like when I’m writing… I’m writing, just like I always did before the internet existed. Part of what I love and crave about writing fiction is that it’s a process that feels timeless and part of my essential self.

C.M. MAYO: Another question apropos of the Digital Revolution. At what point, if any, were you working on paper? Was working on paper necessary for you, or problematic?

JOANNA HERSHON: I certainly wrote on paper for many years until the Microsoft Word option of cutting and pasting became such an integral part of my writing. I still prefer to read manuscripts on paper and to use a pencil to mark them up. More and more though, I use Track Changes in Word and write notes and edit with that program in order to save paper for environmental reasons and also because it’s easy and can be very helpful.

C.M. MAYO: What is the most important piece of advice you would offer to another writer who is just starting out? And, if you could travel back in time, to your own thirty year-old self?

JOANNA HERSHON: Read as much as possible. Carve out time to read and to be silent. Also, move through the world open to mystery and strangeness and meaning. When you walk, when you observe, take in the details and pay attention to what you recall, even if it seems meaningless. There’s usually something worth noting if it stays. As for my thirty year old self: I was writing a LOT when I was thirty, so I think I’d probably say to keep going, but maybe to also travel more before having children.

“Read as much as possible. Carve out time to read and to be silent. Also, move through the world open to mystery and strangeness and meaning.”

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you?

JOANNA HERSHON: I am really not sure. Due to the Corona Virus, I am currently in social isolation in Brooklyn with my family. My kids will begin remote learning in about two weeks. My novel is about to be published. I’d thought I’d be touring and going to book groups and book stores all spring and now I am mostly cooking and cleaning and entertaining my five-year-old. I hope to connect with readers more and more online. It’s hard to imagine that I won’t start another novel and hopefully soon. I have written novels for my entire adult life and it feels like an inextricable part of me.

#

P.S. Check out Joanna Hershon’s guest-blog post for Madam Mayo blog about her novel A Dual Inheritance.

What the Muse Sent Me about the Tenth Muse,

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

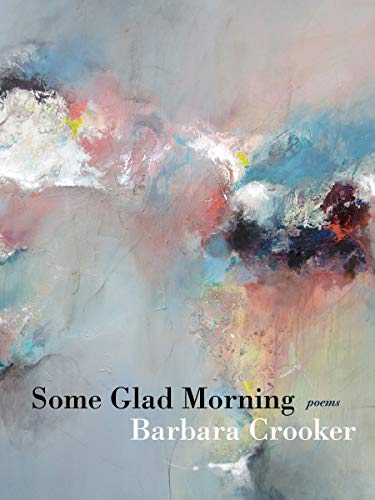

Q & A with Poet Barbara Crooker on the Magic of VCCA,

Reading, and Some Glad Morning

#

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.