While we’re still in the midst of the covid shut-down this Monday, here is one of my favorite travel posts from the archives:

Notes on Artist Xavier González (1898-1993),

“Moonlight Over the Chisos,” and a Visit to

Mexico City’s Antigua Academia de San Carlos

Originally posted on Madam Mayo blog, May 2, 2016

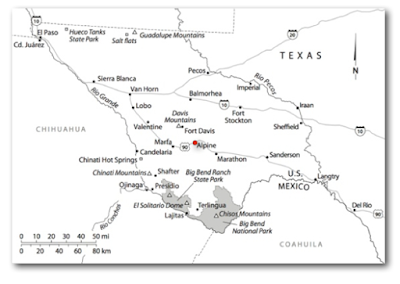

It was in 2012, when I started on my still in-progress book about Far West Texas, that I first encountered the paintings of Xavier González in the Museum of the Big Bend on the Sul Ross University Campus in Alpine, Texas. I was there to see “The Lost Colony,” an exhibition of works by painters associated with the summer Art Colony of the Sul Ross College (now Sul Ross State University). The works were from 1921-1950; the Art Colony, formally so-called, spanned the years 1932-1950.

Curator Mary Bones gave me a fascinating interview about “The Lost Colony,” which you can listen to here.)

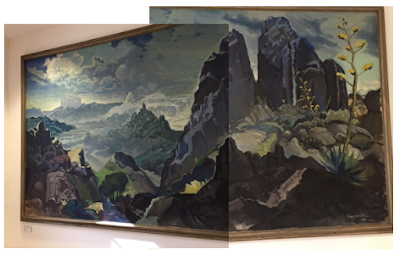

“MOONLIGHT OVER THE CHISOS,” 1934

The artwork by Xavier González that most enchanted me was his magnificent “Moonlight Over the Chisos” of 1934. It was not in the show itself, however, but tucked into the top of the stairwell leading down to the museum’s map collection– not an ideal location, but no doubt one of the few available walls large enough to accommodate the massive 6 x 14 feet canvas.

“Moonlight Over the Chisos” is in the tradition of Mexican murals of the 1930s, although technically not a mural, as it is painted on canvas. (In no way do these two photos, snapped with my iPhone and pasted together with a screenshot, do this masterpiece justice. Alas, the painting is so large, I couldn’t back up far enough to fit the whole of it into one shot.)

(Dear reader, if you haven’t hiked the Chisos, you have yet to live.)

XAVIER GONZÁLEZ IN MEXICO CITY

(RESEARCH UNDERWAY…)

What also caught my attention was that González had studied art in Mexico City and precisely during the time of great muralists, among them, Diego Rivera. Mary Bones told me: “Xavier González spent many summers down in Mexico and Mexico City looking at the muralists.”

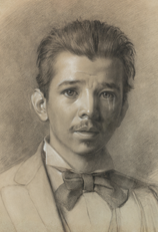

Born in Almería, Spain in 1898, as a child Xavier González immigrated with his family to Mexico.

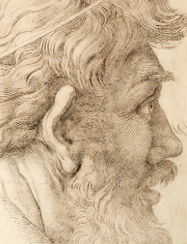

An important influence on his development as an artist was his maternal uncle, the academic painter José Arpa (1858-1952), a native of Spain who later divided his time between Mexico City and San Antonio– and became a leading figure in the art community of the latter, running an art school out of the Witte Museum. According to the notes for “The Three Worlds of Jose Arpa y Perea” exhibition of 2015 from the website of the San Antonio Museum of Art, Arpa won the Rome Prize three times and had been offered the directorship of the Academia de San Carlos, but instead worked independently. In my notes from a visit to González’s archive in the Smithsonian (box 4, unattributed article):

“[José Arpa] received his early art training at the School of Fine Arts in Seville… His first success was in 1891, when his painting of Don Miguel de Manarra won first prize in the Madrid exhibition. Travels in Africa and Europe followed… the Spanish government sent for of his paintings to the first World’s Fair held in Chicago in 1893 as representative of the best of Spain…. shortly after that time the Mexican government sent a man-of-war to Spain and brought him to Mexico to assume charge of the academy of Fine Arts in Mexico City. He later declined the appointment, but remained for many years becoming enthralled with the light and color and movement of the country…”

At age thirteen (circa 1911) Xavier González was studying at the Academia de San Carlos in Mexico City. This was the same time that 15 year old David Siquieros, who was to became one of Mexico’s greatest muralists, was also beginning his studies at San Carlos. (Did they take the same classes?)

In 1913 the violent stage Revolution intervened… I’m still a little foggy on the details of González’s early life…

The Lost Colony catalog notes that González studied and worked as a mechanical engineer. In 1922 he was working in Iowa for a railroad. Later he studied at night and graduated from the Chicago Art Institute. In 1925, he was assisting his uncle José Arpa in his art school in San Antonio’s Witte Museum and from 1927-29 he was teaching classes himself.

González became a US citizen in 1930 and the following year took a faculty position at Sophie Newcomb, the women’s college now folded into Tulane University in New Orleans.

From “The Lost Colony” catalog:

“…much of the work was to be done en plein air with frequent trips to the Davis and Chisos Mountains”

> 1932 González conducted the first summer Art Colony at Sul Ross (along with Julius Woeltz and Aline Rather)

> 1933 González in Paris, and also Mexico City (on a leave of absence from Sophie Newcomb College.)

> 1934-1939 González conducted sessions of the summer Art Colony.

> 1935 González married his student Ethel Edwards.

More about Xavier González:

> New York Times obituary;

> Texas State Historical Association;

> David Dike Gallery;

> Archives of American Art Xavier González papers –and also the papers of his wife, artist Ethel Edwards 1935-1999).

I hope to be able to dig into the archives at the Academia de San Carlos to find out when exactly González attended and with whom he studied. I am also curious to learn why his uncle José Arpa, after coming all the way from Spain, did not take the helm at the Academia de San Carlos.

#

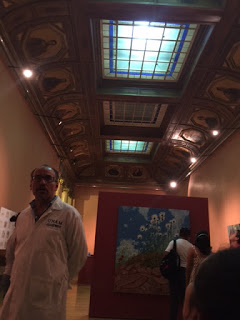

A VISIT TO THE ANTIGUA ACADEMIA DE SAN CARLOS

(Not to be confused with the Museo San Carlos, different building, different neighborhood. Uyy, Mexico City is endlessly endless.)

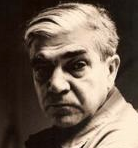

Herewith a batch of notes, GIFs, photos and brief videos from my recent visit to the Antigua Academia de San Carlos which now serves as the National University (UNAM) campus for masters and doctoral degrees in the fine arts. Art history professor Dante Díaz Mendieta leads tours on the last Wednesday of each month. (For details scroll down to the end of this post.)

You’ll find the Antigua Academia de San Carlos a short walk behind the National Palace, at the corner of Moneda and Academia Streets (Calle Moneda y Calle Academia). This GIF shows my approach from Moneda, the National Palace along the right, then the terracotta-colored neoclassic Italianate façade of the Academia de San Carlos.

The site of the Academia de San Carlos has been continually occupied for almost 500 years. The land once backed the Aztec emperor Moctezuma’s palace, Casas Nuevas. After the Conquest the parcel became the property of the Church; the original building arose as a hospital specializing in syphilis patients.

In the late 18th century King Carlos III sent his chief engraver to New Spain– Mexico wasn’t yet Mexico– to establish an academy and so improve the production of coins– hence the Academia de San Carlos’ location, only steps from the Casa de Moneda, the mint for the colony which was founded in 1535.

Classes began in 1781 and the Academia de las Nobles Artes de San Carlos de la Nueva España, offering instruction in architecture, engraving, painting, and sculpture, was officially inaugurated in 1785.

The oldest fine arts academy in the Americas, San Carlos has been in almost continuous operation for 235 years. It closed in 1822, during the cash-strapped years of the First Empire, and not until 1843 did it reopen, when Santa Anna, in a moment of inspiration, joined it to the lottery which became known as the Lotería de San Carlos. According to the Mexican Lottery website (my translation):

“The San Carlos Lottery utilized its income to acquire important artworks, provide scholarships for the Academia de San Carlos, and to bring important teachers to Mexico among them, the painter Pelegrín Clave, sculptor Manuel Vilar, landscape painter Eugenio Landesio and architect Javier Cavallari… Thanks to this lottery’s economic success it was possible to address other large and urgent needs of the general population in a time of foreign invasions and civil wars that left in the country in circumstances of chronic poverty.”

My 49 second video below shows the entrance, then the central patio before “Winged Victory” and brief look at glass dome which was installed by Antonio Rivas Mercado in 1913. According to Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo in I Speak of the City: Mexico City at the Turn of the Twentieth Century (high recommended):

“Antonio Rivas Mercado was one of the few Mexican architects favored with contracts for major national construction projects. But he was a French-trained architect, a follower of the Paris beaux-arts style, who had lived in London and Paris for many years.” (p. 22)

The dome was manufactured in France. Note the Art Nouveau ojos de buey or oval windows, also designed by Rivas Mercado for the section added to help support the dome’s weight. Part of the tour included a jazz concert by Los Cuatro Saxofones (The Four Saxophones).

Here is a much better video made by the university (about 7 minutes, in Spanish):

Winged Victory represents the goddess Nike. Most Mexicans, familiar with the American sports shoe brand, pronounce Nike to rhyme with bike. Professor Díaz Mendieta set his audience straight. In Spanish Nike is pronounced Nee-keh. She is the symbol of the Academia de San Carlos. The other 19th century plaster casts of iconic Greek and Renaissance sculptures, including Michelangelo’s Moses and head of David, are not for decoration but for the students to copy.

This handsome gallery of walnut wood and gold leaf features a ceiling decorated with portraits of artists and scientists including Copernicus and Raphael. A few of the heads fell off during the 1985 earthquake. There was little light by this time, alas; the colors in this room are actually rich and brilliant.

And this is the Centennial Gallery, decorated in the then fashionable Frenchified festoonerie for the academy’s 100th anniversary:

Voilà, Weltschmerzerie and sparkly donuts:

Finally, here is a GIF of Professor Díaz Mendieta wrapping up the tour in the torreo or bullring, an original classroom. The torreo was used not for making art but teaching theory and history of art. No doubt Diego Rivera addressed students here, as did his professor, Santiago Rebull, and many more in a long list of Mexico’s greatest artists.

The desks are notably narrower than in classrooms today. The room (was it windowless?) felt a smidge creepy.

SIDEBAR (FROM ONE VERY MACHO MUNDO):

A FEW OF THE NOTABLE ARTISTS OF THE ACADEMIA DE SAN CARLOS, BY DATE OF BIRTH

José María Velasco (1840-1912)

Antonio Rivas Mercado (1853-1927)

Jesús Fructuoso Contreras (1866-1902)

Dr. Atl (Gerardo Murillo) (1875-1964)

José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949)

Xavier González (1898-1993)

¿FANTASMAS? POR SUPUESTO, AMIGOS

The great glass dome had gone dark when Professor Díaz Mendieta concluded on the wicked note that of course there are ghosts in here: a little girl who laughs; loud knocks; and, as the nightwatchman swears, on occasion in the wee hours of the night, moving from one side of the entrance foyer and disappearing into the opposite wall, a procession of monks holding torchlights.

Recently the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) conducted an excavation that turned up 17 bodies. Presumably these were not of art students but syphilis patients of the 18th, 17th, or even 16th century.

¿Y LA FRIDA?

It’s impossible to talk about Mexican artists without mentioning Frida Kahlo. No, Professor Díaz Mendieta answered the question, Frida did not take classes at the Academia de San Carlos; at that time it was for men only, but Frida hung out here (andaba aquí) with her sweetheart, Diego Rivera.

In a future blog post I will talking about González’s wife Ethel Edwards; also about noted Texas regionalist painter Julius Woeltz (1911-1956), a student of González’s who taught at the summer art colony at Sul Ross and who accompanied González on some of his trips to paint in Mexico City in 1934 and 1935. (Woeltz also served as best man at González’s wedding.) I hope to also unearth more about Woeltz in the archives of the Academia de San Carlos. Stay tuned. Curator Mary Bones also talks about these and many other artists of the “Lost Colony” in my “Marfa Mondays” podcast interview. Again, that recording and transcript are available free here.

#

HOW TO GET THE TOUR

(UPDATE May 18, 2020: I have no idea whether any of this information is still valid. At present, because of the covid, many places in Mexico City remain closed.)

On the last Wednesday of every month, at 7 PM, UNAM art history professor Dante Díaz Mendieta offers a free tour, no reservations required. (In Spanish, of course.) Check for updates on the Facebook pages “Difusión San Carlos” or “GestionCulturalSanCarlos” or call tel. 5522-0630 ext 228.

A tour of the Academia de San Carlos is also included in the annual Festival del Centro Histórico de la Ciudad de México. The 2016 Festival concluded in March; look for it again in 2017.

A Visit to the Casa de la Primera Imprenta de América

in Mexico City

What the Muse Sent Me about the Tenth Muse,

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

#

Find out more about

C.M. Mayo’s books, articles, podcasts, and more.