This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

We have never met, but I feel as if we have. I think this is always true when one has read another’s such wonderful writing. But I did “meet” Diana Anhalt, in a matter of speaking, when years ago, she sent me a selection from her powerful and fascinating history / memoir of growing up in Mexico City, A Gathering of Fugitives: American Political Expatriates in Mexico 1948-1965. When, sometime later, I read the entirety of that beautifully written book itself–which I admiringly recommend to anyone with an interest in Mexico–I wrote to her, and we have kept in touch ever since. Apart from writing poetry and essay, we have this common: a lifetime, it seems, of living in Mexico City, and married to a Mexican. By the time we found each other’s work, however, Diana and her husband Mauricio had left “the endless city” for Atlanta, Georgia. (But ojalá, we will meet one day outside of cyberspace soon!)

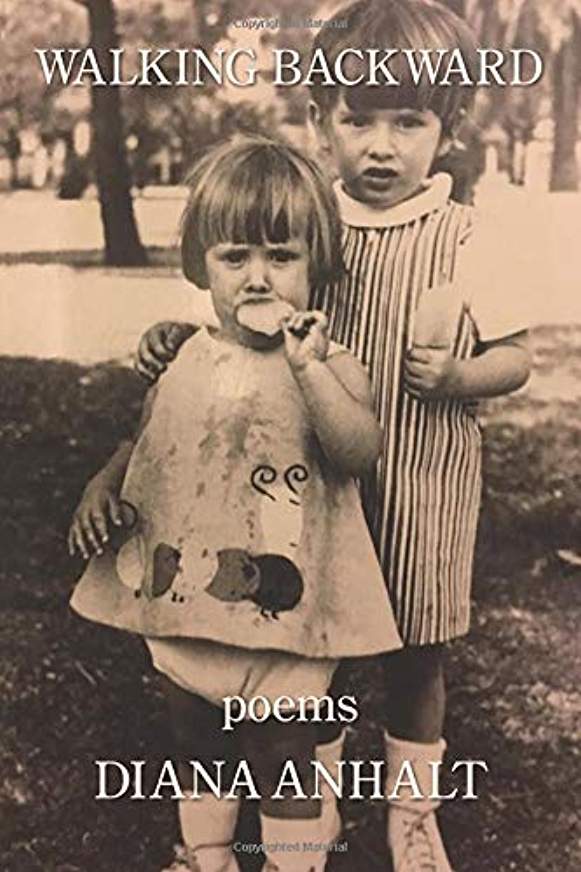

Her latest, just out from Kelsay Books, is Walking Backward. From her publisher’s website, her author bio:

“Diana Anhalt left Mexico over nine years ago following close to a lifetime in that country but claims her writing sometimes digs in its heels and refuses to budge. She continues to write about Mexico. Many of her essays, short stories, and book reviews have appeared in both English and Spanish along with her book, A Gathering of Fugitives: American Political Expatriates in Mexico 1948-1965. Since she first arrived in Atlanta, two of her chapbooks, Second Skin, (Future Cycle Press), Lives of Straw, (Finishing Line Press), and one short collection, Because There Is No Return, (Passager Books), have been published. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in “Nimrod,” “Concho River Review,” “The Connecticut River Review,” “The Atlanta Review,” and “Spillway,” among many others. She believes this is the first time her work has started to lose its Mexican accent.”

Source: Kelsay Books

Writes Dan Veach, founding editor of Atlanta Review, author of Elephant Water and Lunchboxes:

“The best way to visit any country is with someone who knows and loves it intimately. In Walking Backward, Diana Anhalt welcomes us graciously into the very heart of her family and her Mexico. With deep empathy and quiet courage, and always with a saving grace of humor, she shows us how to deal with love and loss, both on a personal and an artistic level.”

#

C.M. MAYO: What inspired you to write Walking Backward?

DIANA ANHALT: I wanted to put together a collection—this is my fifth—which would include, for the first time, some of what I’d written following my husband’s death three years ago, but it couldn’t just be a book about death so I settled on including, as well, work focused on the family, on the past.

MISSING

by Diana Anhalt

I walk my unwritten poems down La Reforma,

stop to buy La Prensa, scan the Want Ads.

Missing bilingual parrot Inglés/Español,

answers to the name of Palomitas.

Se Busca María Felix look-alike for chachacha-ing

on Saturday nights. Extraviado/Lost guitar case

filled with woman’s shoes and toothpaste samples.

In Search Of instructions on how to read divining bones.

Reward Offered for information leading to whereabouts

of Gabi Escobedo, missing since September.

Attención Mauricio—You’ve been dead long enough.

It’s time to come home.

Reprinted by permission of the author from Walking Backwards, Kelsay Books, 2019 Copyright © Diana Anhalt

C.M. MAYO: If a reader were to read one poem in this collection, which one would you suggest, and why?

DIANA ANHALT: The logical choice would be Walking Backward, the title poem and the first in the book. After Mauricio and I left Mexico and the home where we had lived for many years, I’d wake up in the middle of the night to go to the kitchen or the bathroom only to discover my feet walking in the direction they would have taken in my Mexican home, not here in Atlanta. The title’s suggestion of walking and residing in the past was what I was aiming for.

[SCROLL DOWN TO THE END OF THIS POST READ THE POEM, “WALKING BACKWARD”]

C.M. MAYO: Can you talk about which poets and writers have been the most important influences for you?

DIANA ANHALT: It’s changed, of course, over the years, but more recently I was very fortunate to belong to a group which worked closely with the head of the Georgia Tech poetry program, the late Tom Lux, who became a mentor and friend. Tom facilitated our interaction with the poets Ginger Murchinson and Laure Ann Bosselar. Richard Blanco and a number of wonderful poets in our Poetry Workshop and others writing here in Atlanta have also influenced my poetry.

C.M. MAYO: Which poets / writers are you reading now?

DIANA ANHALT: Here: Poems for the Planet, a recent anthology, edited by poet Elizabeth Coleman, Jo Harjo, our new U.S. poet laureate, and Land of Fire by Mario Chard. I’ve also been reading Jennifer Clement’s Gun Love and Fatima Farheen Mirza’s A Place for Us.

C.M. MAYO: You have been a productive poet and writer for many years. How has the Digital Revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

DIANA ANHALT: You’ve expressed it well. It has been challenging to stay focused and I’m afraid that, as of now, I’m still incapable of using it fully to my advantage—I don’t use social media— but I do find the Internet extraordinarily helpful at times in establishing contacts, finding venues and staying in touch.

C.M. MAYO: Another question apropos of the Digital Revolution. At what point, if any, were you working on paper? Was working on paper necessary for you, or problematic?

DIANA ANHALT: I had always worked on paper but once I began to write on the computer I found the ability to make changes and save the many versions necessary in producing a poem very helpful. I still keep a notebook, transfer the notes to the computer, and do the actual writing on the computer.

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you as a writer / poet?

DIANA ANHALT: Now that Walking Backward is out I will continue to produce for our monthly poetry workshop meetings, send my work out, enter a contest or two but I do hope to get back and revise my now outdated computer files for A Gathering of Fugitives: American Political Expatriates in Mexico 1948-1965. (Although I must admit that I’ve been promising myself to do that for years. Still haven’t.)

Use ‘heel’ and ‘toe’ as verbs

WALKING BACKWARD

By Diana Anhalt

Late each night I rose, woozy with sleep

and my bare feet traveled blind—knew

one room from the next through cracks

in the wood, space between floorboards,

sensed their width, breadth, girth…

For forty years I called that same place home—

Left it, yet it resides in me. The feet are last

to follow. They fumble the unfamiliar,

reject the waxed surface of a new life,

are the last to forgive my leaving, long

to return me to the old home—wet wash

pinned to a line in the courtyard, scent of chili

and cilantro wafting from the kitchen.

At night they lurch backwards into the past,

tread the dream halls where faces linger

in mirrors, Spanish echoes down corridors

into a past I thought I’d left behind—

And there you are. You wait in the doorway,

lean against the door frame and ask: Como te fue?

How did it go? Red wine or white?

Walking Backward

Late each night you rose, woozy with sleep,

the space your familiar, and your bare feet traveled

it blind—knew one room from the next through

cracks in the wood, space between floorboards,

splinters, sensed their width, breadth girth.

For forty years you called the same place home—

Leave it, yet it resides in you. The feet are last to follow.

They fumble the unfamiliar, reject the waxed surface

of a new life, are the last to forgive your leaving,

long to return you to the old home—wet wash

pinned to a line in the courtyard, scent of chili

and cilantro wafting from the kitchen.

At night they lurch backwards into the past,

tread dream halls where faces linger

in mirrors, Spanish echoes down corridors

into a past you thought you’d left behind—

And there you are. You wait in the doorway,

lean against the door frame and ask: “Como te fue?”

How did it go? Red wine or white?

They cleave to familiar roadways. The late night path between bed and bathroom.

Your feet are the last to forgive you.

The feet are the last to forgive your leaving

murky

Leading you down a hall you left behind. (no longer there)

You alongside

(forgive)

(home) in the cracks between boards. (where your Spanish song)

(And when you leave) The feet are the last to forgive your leaving home

Footsteps lurk in the past. My feet tread the past.

Your feet are the last to forgive you. (to forgive your wandering.)

You abandon your past

My feet still know a past when….

Tide erases footsteps on the sand.

Bare feet, it’s time to get used to this,

this unknown space, a floor less friendly,

rougher on your soles, less familiar with

your tread, colder, tile not wood

The tug of familiar surfaces

Today after a deep sleep my feet walk me

Toward the door I left behind

down a hallway I left behind.

No longer there.

Xxxxxxxxxxxx

Late each night you rise, woozy with sleep,the space your familiar, and your bare feet travel

it blind—tread those same midnight floorboards

sense their width, breadth girth,

know one room from another through cracks in the wood,

They tread the past.

Lingered behind in the familiar

Who thought to warn them? I forgot to warn them.(you)

Late at night, woozy with (from) sleep

I forget to tread the slippery smoothness of new floors

(I forget and tread the old floors)

through hallways silenced by sleep, dizzy with sleep

Foothold, heel and toe

My body owns (keeps, retains) the compass, (encompasses)

Maps (traces) the floors I left behind.

My footsteps tread past.

retrace ones steps

(If you) live in the same place for 40 years. (Call one place home)

tread the same midnight floorboards

That place resides in you.

(When) You rise at night, the floor is your familiar

and your bare feet travel it—feel it’s width, breadth girth,

Know one space from another

by the cracks in the wood,

a shaky floorboard,

(After years treading the same midnight floorboards)

Today, late at night, woozy with (from) sleep

After years of treading darkened halls feet knewthose floors and follow them.

They seek the familiar groundwork of the past, late to discover it’s disappeared.

(no longer there.)

I argue with my feet (An argument with my feet)

Earlier notes

I walk away from forty years of my life

Awakened to darkness, late at night my feet

refuse to travel,

walk the dark, down the hall you left behind

Remind me that I never thought to tell them:

For forty years you call the same place home

and each night, woozy with sleep, your feet

tread those same midnight floorboards

until

My feet still remember a past when

your feet

tread those same midnight floorboards

until that place resides in you

Awakened from a deep

Nudged into the past

Nudge words into meaning

When I left I forgot to tell (warn) my feet. They stayed

Behind entrenched in the familiar streets of home

Go through the process of leaving

I forgot to tell you. (them) (warn them)

When I left I forgot to tell (warn) my feet.

they linger behind

Behind

Highways, biways.

At home on bicycle pedals.

My feet, unlike the rest of me, refuse to take the lead (to follow my lead)

Highways, biways.

At home on bicycle pedals.

My feet, unlike the rest of me, refuse to take the lead (to follow my lead)

When I rise from bed late at night in this new place

fuzzy (heavy) with sleep

Feet speak a language of their own

The scurry, scrape against the floor

New territory (territorial)

I try to reason with my feet.

Abandon home after forty years, last to follow

are the feet. They fumble the unfamiliar, reject

the waxed surface

of new floors. (newness)

They reject the slippery smoothness of new floors

They forget to tread the slippery smoothness of new floors

And fumble in the unfamiliar

(I forget and tread the old floors)

through hallways silenced by sleep, dizzy with sleep

When you abandon (leave) home after 60 years. the feet are the last to follow.

Mine, at home in the past, learned (memorized) the floors—width, breadth, girth

Today, in this new place, they move (walk) (grope) backwards into (retrieving) the past late at night, woozy with sleep,

reject the slippery smoothness of new floors

forget to tread the slippery smoothness of new floors

fumble with the unfamiliar

The late night path (track another word-meaning destination?) between bed and bathroom.

You abandon your past

Reprinted by permission of the author from Walking Backwards, Kelsay Books, 2019 Copyright © Diana Anhalt

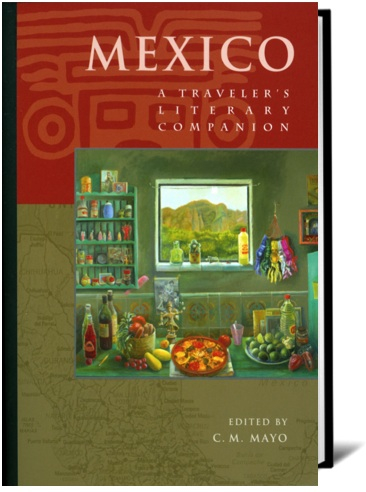

>> Look for Walking Backward at amazon and at Kelsay Books.

>> See also Diana Anhalt’s guest-blog for Madam Mayo in 2015 on “Five Books that Inspire Poetry.”

>>More Q & As at Madam Mayo blog here.

Q & A: W. Nick Hill on Sleight Work and Mucho Más

Who Was B. Traven? Timothy Heyman on The Triumph of Traven

What the Muse Sent Me About the Tenth Muse, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

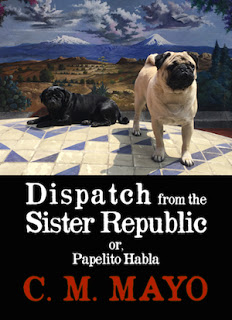

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.