This blog posts on Mondays. This year, 2021, I am dedicating the first Monday of the month to Texas Books, in which I share with you some of the more unusual and interesting books in the Texas Bibliothek, that is, my working library. Listen in any time to the related podcast series.

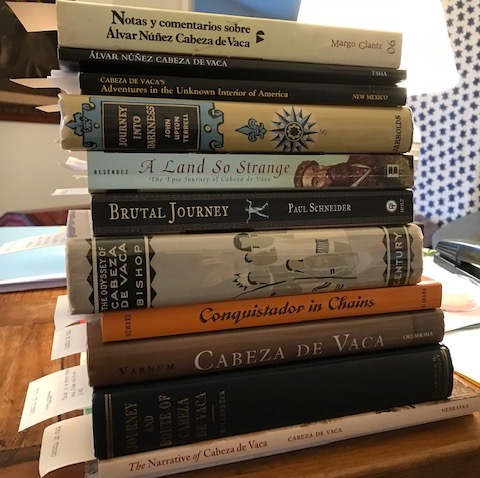

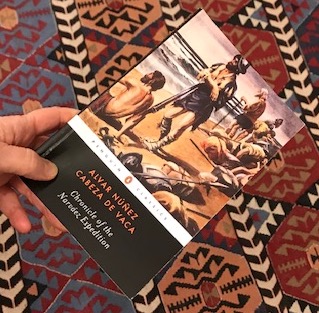

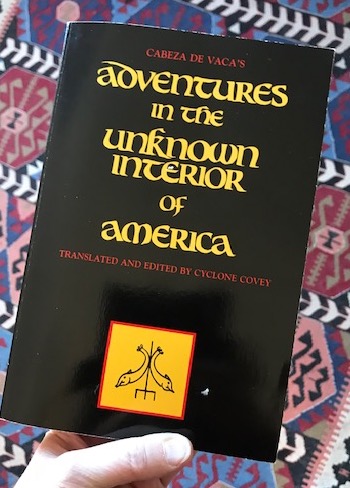

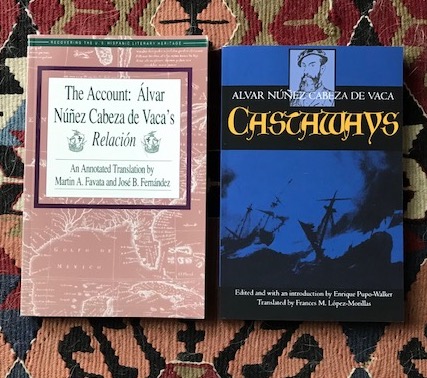

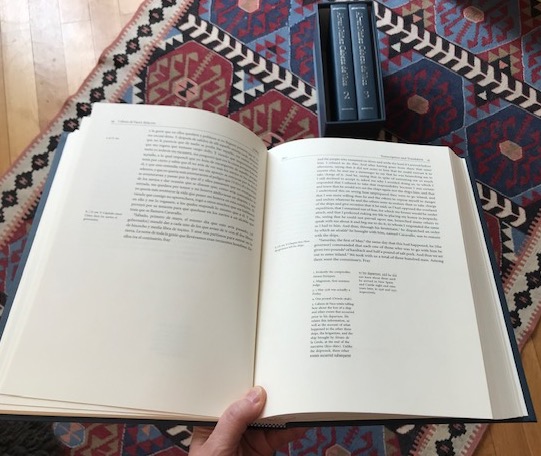

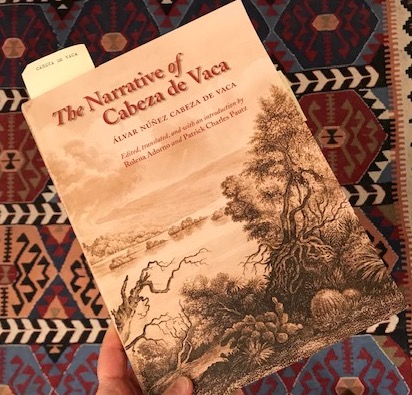

Last month I posted Part I of Selected Cabeza de Vaca Books, spotlighting the 1542 and 1555 editions and the various English translations of Cabeza de Vaca’s La Relación. (These translations included the Smith, Bandelier, Covey, and the perhaps unsurpassable Adorno and Pautz.) Herewith, for Part II, I offer some notes, tackled chronologically by their date of publication, on notable biographies and narrative histories of Cabeza de Vaca’s North American odyssey which I happen to have at-hand in my working library— what I have dubbed the Texas Bibliothek.

(By the way, my own longform essay available on Kindle, “Dispatch from the Sister Republic or, Papelito Habla,” discusses Cabeza de Vaca’s odyssey and La Relación within a broader meditation on the Mexican literary landscape—not the usual take for a work in English.)

*

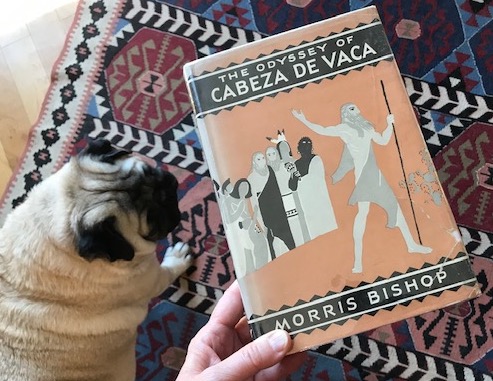

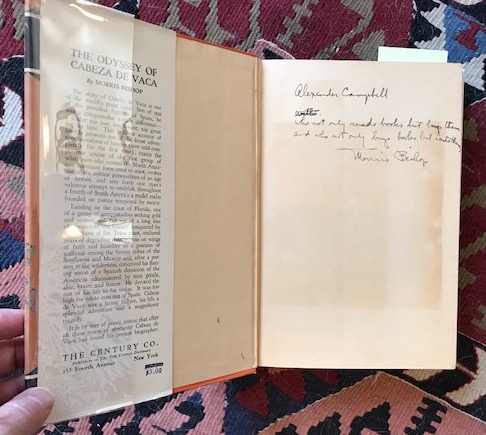

MORRIS BISHOP

Morris Bishop’s The Odyssey of Cabeza de Vaca (The Century Company, 1933) isn’t really necessary for my working library because, for all practical purposes, for the work of creative nonfiction I am writing, I can rely on the more recent and excellent scholarship of Adorno and Pautz and Reséndez. But I recognize the cultural / historical importance of Bishop’s work and so, for a relatively reasonable price, I wanted to have a first signed edition in my collection. (So, is what I have a working library or a rare book collection? I ask myself that every other day!)

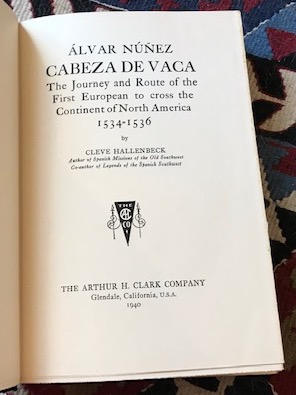

CLEVE HALLENBECH

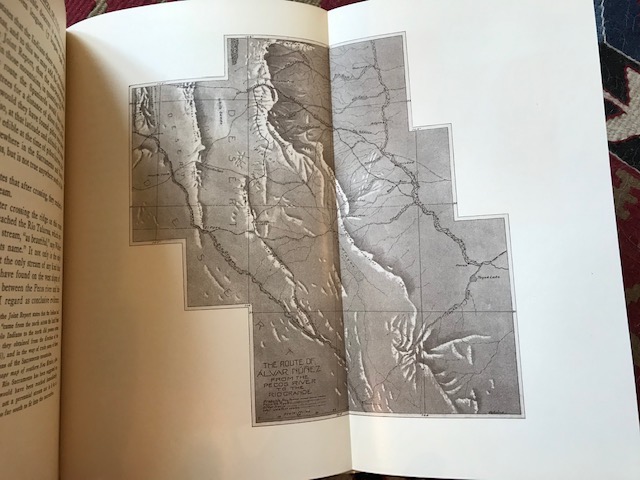

Cleve Hallenbech’s Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca: The Journey and Route of the First European to Cross the Continent of North America 1534-1536 (The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1940) is another work I do not absolutely require for my working library but which, in recognition of its cultural and historic importance, and the very reasonable price for a near-fine first edition, I wanted to have in my collection.

That said, the maps are a wonder! I’ll be talking about these in my post, Part III, for the first Monday of next month, when I discuss the routes various scholars have proposed for Cabeza de Vaca.

JOHN UPTON TERRELL

John Upton Terrell’s Journey Into Darkness: Cabeza de Vaca’s Expedition Across North America 1528-36 (Jarrolds Publishers, 1964) is well-researched, given the resources the author had access to back in the early 1960s, and aimed at the general reader.

DAVID A. HOWARD

David A. Howard’s Conquistador in Chains: Cabeza de Vaca and the Indians of the Americas (University of Alabama Press, 1997) —currently reading. I was tremendously curious to learn more about Cabeza de Vaca’s later adventures in South America, which are rarely considered in-depth, lying as they do in the shadow of his epic journey in North America.

ALEX D. KRIEGER

We Came Naked and Barefoot: The Journey of Cabeza de Vaca Across North America (University of Texas Press, 2002)—currently reading.

From the catalog copy:

“Perhaps no one has ever been such a survivor as Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. Member of a 600-man expedition sent out from Spain to colonize ‘La Florida’ in 1527, he survived a failed exploration of the west coast of Florida, an open-boat crossing of the Gulf of Mexico, shipwreck on the Texas coast, six years of captivity among native peoples, and an arduous, overland journey in which he and the three other remaining survivors of the original expedition walked some 1,500 miles from the central Texas coast to the Gulf of California, then another 1,300 miles to Mexico City.

“The story of Cabeza de Vaca has been told many times, beginning with his own account, Relación de los naufragios, which was included and amplified in Gonzalo Fernando de Oviedo y Váldez’s Historia general de las Indias. Yet the route taken by Cabeza de Vaca and his companions remains the subject of enduring controversy. In this book, Alex D. Krieger correlates the accounts in these two primary sources with his own extensive knowledge of the geography, archaeology, and anthropology of southern Texas and northern Mexico to plot out stage by stage the most probable route of the 2,800-mile journey of Cabeza de Vaca.

“This book consists of several parts, foremost of which is the original English version of Alex Krieger’s dissertation (edited by Margery Krieger), in which he traces the route of Cabeza de Vaca and his companions from the coast of Texas to Spanish settlements in western Mexico. This document is rich in information about the native groups, vegetation, geography, and material culture that the companions encountered. Thomas R. Hester’s foreword and afterword set the 1955 dissertation in the context of more recent scholarship and archaeological discoveries, some of which have supported Krieger’s plot of the journey. Margery Krieger’s preface explains how she prepared her late husband’s work for publication. Alex Krieger’s original translations of the Cabeza de Vaca and Oviedo accounts round out the volume.”

*

ANDRÉS RESÉNDEZ

Ring-a-ling to Dr. Jung! Reséndez and Schneider (below) both published their narrative histories about Cabeza de Vaca’s epic journey in North America in the same year, 2007. Andrés Reséndez’s A Land So Strange: The Epic Journey of Cabeza de Vaca (Basic Books, 2007) is an award-winning historian’s beautifully written and extensively footnoted narrative history. No one writing about Cabeza de Vaca, whether creative writer or serious scholar, should overlook Reséndez’s masterwork. I went for the paperback so that I could mark it up with my pencil all whichways.

*

PAUL SCHNEIDER

Paul Schneider’s Brutal Journey: Cabeza de Vaca and the Epic First Crossing of North America (Henry Holt, 2007) is a riproaring adventure read, well-researched and elegantly written, and one I would warmly recommend to the general reader.

The catalog copy gives the explosive flavor:

“A gripping survival epic, Brutal Journey tells the story of an army of would-be conquerors, bound for glory, who landed in Florida in 1528. But only four of the four hundred would survive: eight years and some five thousand miles later, three Spaniards and a black Moroccan wandered out of the wilderness to the north of the Rio Grande and into Cortes’s gold-drenched Mexico. The survivors of the Narváez expedition brought nothing back other than their story, but what a tale it was. They had become killers and cannibals, torturers and torture victims, slavers and enslaved. They became faith healers, arms dealers, canoe thieves, spider eaters. They became, in other words, whatever it took to stay alive.”

*

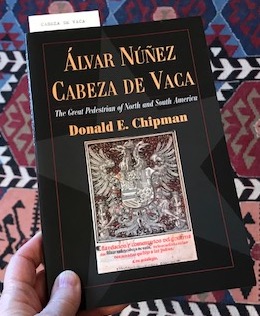

DONALD E. CHIPMAN

Donald E. Chipman’s Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca: The Great Pedestrian of North and South America (The Texas State Historical Association, 2012) offers a short (only 70 pages), albeit authoritative overview by an academic historian for those with an interest also in Cabeza de Vaca’s South American odyssey. From the book’s back cover:

“Between 1528 and 1536, explorer Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca trekked an estimated 2,480 to 2,640 miles of North American terrain from the Texas coast near Galveston Island to San Miguel de Culiacán near the Pacific coast of Mexico. Later he served as the royal governor of Asunción, Paraguay. His mode of transportation, afoot on portions of two continents in the early decades of the sixteenth century, fits one dictionary definition of the word ‘pedestrian.’ By no means, however, should the ancillary meanings of ‘commonplace’ or ‘prosaic’ be applied to the man, or his remarkable adventures. This book examines the two great ‘journeys’ of Cabeza de Vaca—his extraordinary adventures on two continents and his remarkable growth as a humanitarian.”

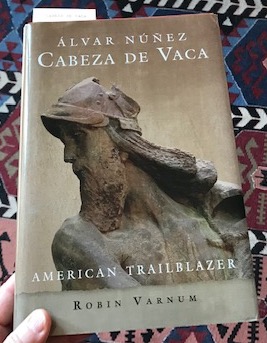

ROBIN VARNUM

Robin Varnum’s Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca: American Trailblazer (University of Oklahoma Press, 2014) is an accomplished and, as best I can ascertain, the latest scholarly biography.

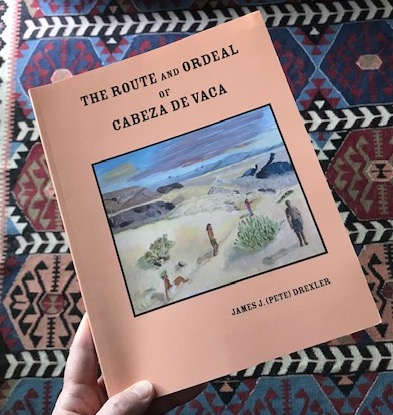

JAMES J. (PETE) DREXLER

The Route and Ordeal of Cabeza de Vaca (self-published, 2016)—currently reading.

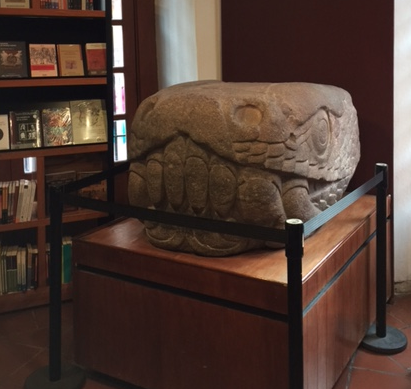

Cabeza de Vaca’s adventures as passed on to us from his La Relación have spawned a small but enduring cottage industry of books, essays, documentaries, websites, and more, which started picking up serious steam over the 20th century. My own sense is that we will see books about Cabeza de Vaca being published for as long as we have books, and I expect books to go on, at one scale or another, for many hundreds of years more. Movies and videos and websites and electronic whatnots? That, too. How about an opera?

*

In “Selected Cabeza de Vaca Books, Part III,” to be posted the first Monday of next month, July 2021, I will be discussing the wackadoodle differences in the various maps of Cabeza de Vaca’s epic journey, with a focus on his route through what we know now as Far West Texas.

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me by simply clicking here.

Selected Cabeza de Vaca Books, Part I:

Notes on the Two Editions of Cabeza de Vaca’s La Relación

(Also Known as Account, Chronicle, Narrative, Castaways, Report & etc.)

and Selected English Translations

Carolyn E. Boyd’s The White Shaman Mural

From the Texas Bibliothek: The Sanderson Flood of 1965;

Faded Rimrock Memories;

Terrell County, Texas: Its Past, Its People

*

My new book is Meteor

Find out more about

C.M. Mayo’s books, articles, podcasts, and more.