This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

Sergio Troncoso is a writer and literary activist whom I greatly admire. It so happens that we were born the same year in the same city: El Paso, Texas. And both of us lived our adult lives in cultural environments vastly different from El Paso: I went to Mexico City; Sergio to Harvard, Yale, and many years in New York City. Sergio’s works offer a wise, deeply considered, and highly original perspective on American culture. I’ve reviewed some of his work here and here; back in 2012 I interviewed him at length about his life and work for my occasional podcast series, Conversations With Other Writers, which you can listen in to anytime here. In the years since he has since published an impressive number of highly accomplished works, both fiction and nonfiction, his latest a collection of short stories, A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son.

C.M. MAYO: What inspires you to write short fiction, as opposed to a novel or nonfiction?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: In this particular collection, A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son, I wanted to focus on short fiction because it allowed me to play with perspectivism and the fragmentation of characters in a way that a longer work (like a novel) would not. These thirteen stories on immigration and Mexican-American diaspora are linked together: a character appears in a group of stories, only to reappear in the next story from a different angle or perspective. The individual stories also build on each other to ask the reader to question herself as to how she brings certain biases and prejudices to certain characters, how the reader herself contributes to this perspectival and temporal truth, which philosophers like Friedrich Nietzsche focused on and writers like Virgina Woolf also explored. So the book is this fragmented whole, in a way, in which the fragments are visible in the form of stories (and the whole is understood only by the reader).

C.M. MAYO: Of all the stories in this collection which is the one you feel most proud of? And why?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: I conceived this book as a whole of stories, as a puzzle in thirteen pieces. So it’s difficult to single out one story. But I am fond of “Eternal Return,” the final story, because it stands alone to bring together many of the themes in the other stories, this playing with perspectivism and time, the presence of ancestors and geographies long gone, the shifting self trying to come together in many selves, all with the existential tick-tock of the clock that reminds us every day that our time on earth is limited. Even if time is always short, we must come together as a self, even if so many forces pull us apart.

C.M. MAYO: If a reader were to only read one story, which would you recommend?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: I would recommend the first story, “Rosary on the Border.” This story begins with a death (as does “Eternal Return,” but death in another form, so to speak), and it takes you into the realism of David Calderon’s life. He tries to makes sense of his father’s death, of his life in relation to the finality that David sees before him. So David sees and appreciates, in bittersweet moments, what his father and mother taught him, even as he has separated himself from them. So it’s an easily accessible (realistic) story that begins a journey for the reader that ends with the more magical-realist “Eternal Return” and another concept of ‘death’ and ‘ancestor.’

C.M. MAYO: If a reader were to take away one sentence (or two or three) from this story, which would you suggest, and why?“

SERGIO TRONCOSO: “I believed in very little, but I kept going until I would get tired or defeated, and then I would take time to discover another wall to throw myself at. I was, and I am, and I will be, a peculiar kind of immigrant’s son. I got old, and that made everything better, including me.”These sentences from “Rosary on the Border” encapsulate David’s effort to search through his past to find out what belongs with him still, and to rid himself of ideas and superstitions that through experience lost their meaning, and yet to go back to who he was, an immigrant’s son, what’s left of this sense of self, to move forward in his life.

C.M. MAYO: Can you talk about which writers have been the most important influences for you?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: Different writers have been influential at different times in my life. When I was a teenager, I loved S.E. Hinton, because her young-adult novels reflected much of my life in Ysleta, with gangs and poverty and being ‘outsiders.’ In college, I started reading the great Latin American writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Isabel Allende, Ruben Dario, Gabriela Mistral, and later I kept going with Pablo Neruda and Jorge Luis Borges. The list of Latin American writers I read is too long! It’s a treasure trove of great writing in Latin America. In the subway, for many years, I would read and reread Emily Dickinson’s collected works, because I loved her lines and the rhythms of her sentences, and because I was taken in by her unique, deeply curious perspective that had little to do with commercial publishing or becoming a celebrity. I love that kind of fiercely independent, insular writing into the soul.

C.M. MAYO: Which writers are you reading now?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: I’ve read many of the works of Valeria Luiselli, a Mexican writer who is such an innovator with narrative form. I’m enjoying works by Francisco Cantu and Octavio Solis, as well as poetry by Sasha Pimentel and Megan Peak. I’m not a poet, but I love reading poetry. Also, I’m a fan of George Saunders: he is just a master of the short story, and his novel Lincoln in the Bardo introduced me to a new (or unusual) narrative form in a longer work.

C.M. MAYO: You have been a productive writer for many years. How has the Digital Revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: I think you have to be relentless about getting the word out about your books and appearances on social media, you have to accept this ‘fast world’ as our world now, even though sometimes I hate it, and you have to do your best not to lose yourself in the posting and re-posting and stupid arguments that too often occur digitally. I do it, then I go back to my work. So I feel a bit schizophrenic sometimes, but I do relish the moment when I turn everything off and lose myself in my work or on a particularly thorny issue of craft. I think you almost have to have a ‘segmented mind,’ that is, learn to function in the realms of social media effectively. But then also learn to take all of this digital frenzy somewhat skeptically. The most basic way it’s affected my writing is that now I write about it, in dystopian stories about where I think our country might be headed, with people too quick to judge superficially, so enamored with images, so lost in our digital world that the real world becomes an aside.

C.M. MAYO: Another question apropos of the Digital Revolution. At what point, if any, were you working on paper? Was working on paper necessary for you, or problematic?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: I still work on paper, after I edit on my computer. I always print any story or novel several times and edit it line-by-line on sheets of paper. I write notes in the white space in the back, as I edit, to add or subtract or plan ahead, as I discard, change, add. I like the going back and forth, between words on paper and words on a computer: this back and forth always gives me a new perspective on what I have on the page, and I need that as an editor.

C.M. MAYO: What is the most important piece of advice you would offer to another writer who is just starting out? And, if you could travel back in time, to your own thirty year-old self?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: Read as if your life depended on it. Read critically in the area you are thinking of writing. Don’t be an idiot: seek out and appreciate the help of others who are trying to help you by pointing out your errors, your lapses in creating your literary aesthetic. Get a good night’s sleep: if you do, you’ll be ready to write new work the next day. And if you fail, you won’t destroy yourself because you did. You’ll be ready to sit in your chair the next day.

“Read as if your life depended on it. Read critically in the area you are thinking of writing.”

C.M. MAYO: In recent years you have been a very active member of the Texas Institute of Letters (TIL). Can you talk a little about your vision for and the value of this organization?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: I’m the current vice president of the TIL. I’m also the webmaster. I’ve actually had a lot of roles in the TIL, official and unofficial. I’m just trying to help. I believe we can nurture a great community of writers in Texas that honors the independence and excellence of past members, while reaching out to communities within our state who are producing great writers but have often been ignored. Mexican-American writers, for example. So not only have we modernized the TIL by taking much of our work and ability to pay dues online, but we have also inducted more women and people of color. We have also held our annual meeting in places we’ve never been, like El Paso and McAllen, so that we represent the entire state of Texas, and not just the orbit around Austin. With our lifetime achievement award, we have honored more women than ever before (Sarah Bird, Pat Mora, Sandra Cisneros, Naomi Shihab Nye). And just a few days ago, we announced that John Rechy has won our 2020 Lon Tinkle Lifetime Achievement Award. So we are recognizing the excellence that was always there, while also being inclusive. As my grandmother often said, “Quien adelante no ve atras se queda.” One who doesn’t look forward is left behind.

“As my grandmother often said,

‘Quien adelante no ve atras se queda.’

One who doesn’t look forward is left behind.“

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you as a writer?

SERGIO TRONCOSO: I just signed a contract with Cinco Puntos Press for a new novel, tentatively entitled as Nobody’s Pilgrims, which I have already written. I’ll be working on editing it. Also, I’m the editor of a new anthology, Nepantla Familias: A Mexican-American Anthology of Literature on Families in between Worlds. What family values from Mexican-American heritage have helped the writer (or the protagonist or narrator) become who she is, and what family values did she discard or adapt or change to become who she wanted to be? This is the ‘in between moment’ that is the focus of this literary anthology. I am always busy, but that’s how I like it. The more I do, the more I can do.

>Visit Sergio Troncoso at www.sergiotroncoso.com

>More Q & As at Madam Mayo blog here.

Waaaay Out to the Big Bend of Far West Texas,

and a Note on El Paso’s Elroy Bode

Q & A with Sara Mansfield Taber on

Chance Particulars: A Writer’s Field Notebook

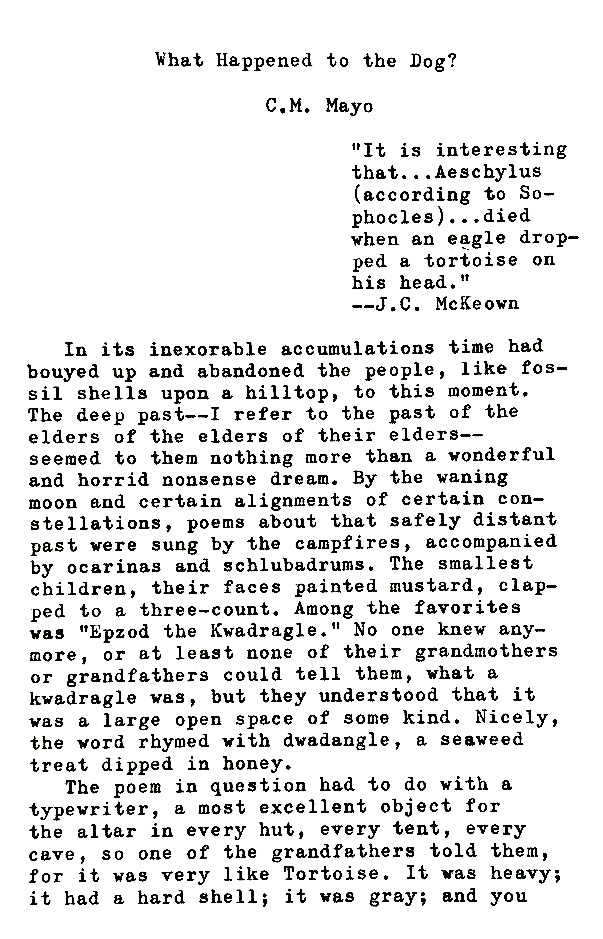

“What Happened to the Dog?” A Story About a Typewriter, Actually, Typed on a 1967 Hermes 3000

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.