“Simple tiny steps of work. I find I actually get a lot done in a shorter amount of time than when I was younger.”

–Katherine Dunn

This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

This month’s Q & A is with visual artist and writer Katherine Dunn, whom I admire more than I can say. I have one of her artworks in the entrance of my house, and another framed in my office, such that I see them both every day–and they always lift my spirits. And I’ve been reading her blog, Apifera Farm, since the dawn of blogging. Her blog can be charming, but dear writerly reader, it’s deeply wise, and it oftentimes features posts about and photos of death (read what she has to say about that here). Her farm, originally in Oregon, is an unusual one. Now relocated to loveliest Maine, Apifera is an incorporated non profit and registered 501[c][3] with a mission to adopt and care for elder/special needs barn animals/creatures and to bring the animals together with elder/special needs people for mutually healing visits.

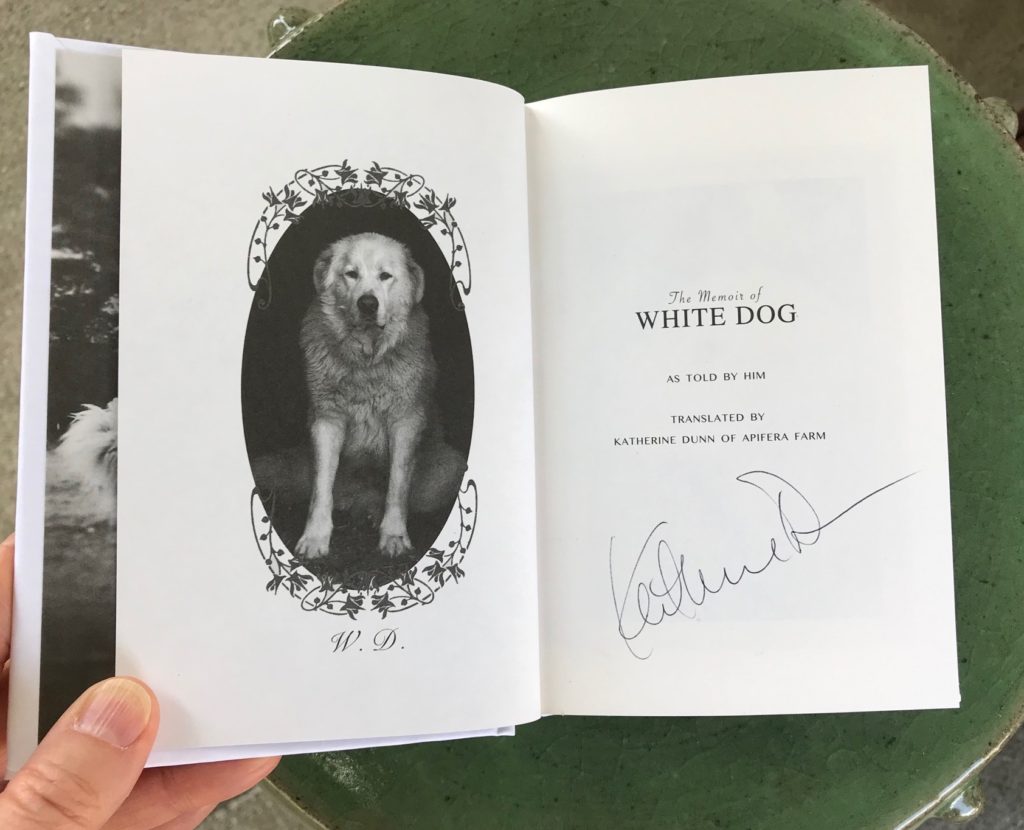

Katherine Dunn’s latest of many books is the exquisite four-color and offset-printed White Dog, and apropos of that, she agreed to answer some questions.

C.M. MAYO: What inspired you to write this book?

Katherine Dunn: White Dog! The mystery of where he really came from was always on my mind. Many opinions were given at the time. But in the end, I stayed with the ‘magic’ of his arrival. All my life I find I am put in situations, that if I had been somewhere else on that day my life would have taken another path. I feel that way with White Dog, I believe he came to help me as much as me to help him.

C.M. MAYO: As you were writing, did you have in mind an ideal reader?

Katherine Dunn: I’m self-taught really. I never think about who is reading or viewing my art.

C.M. MAYO: Now that it has been published, can you describe the ideal reader for this book as you see him or her now?

Katherine Dunn: I just don’t think in those terms I guess. I feel my work is cross generational. When I tried to get into publishing houses for my children books, I was often told they were too adult. When I shared memoirs or story ideas with some agent or editors I was told they weren’t adult enough or did not have an easy to label genre. YUCK. I gave up trying to find an agent or editor after about 5 years.

C.M. MAYO: Which writers have been the most important influences for you?

Katherine Dunn: E.B. White. Marquez. I loved Watership Down. Bob Dylan. Nick Cave. I don’t differentiate between mediums. I think music has been more important to me versus books, although I love books.

C.M. MAYO: You are also a wonderful artist. Which artists have been the most influential for you?

Katherine Dunn: I was surrounded by art and books as a child, my father was an artist/architect. Matisse was an early influence… but Paul Klee I think influenced me the most as child. I was a ceramicist first, and 3d is still part of my work. I need to always be working in a flow of what I want to work on. Lately I’m working on some needle stuff (slowly).

C.M. MAYO: Which writers are you reading now?

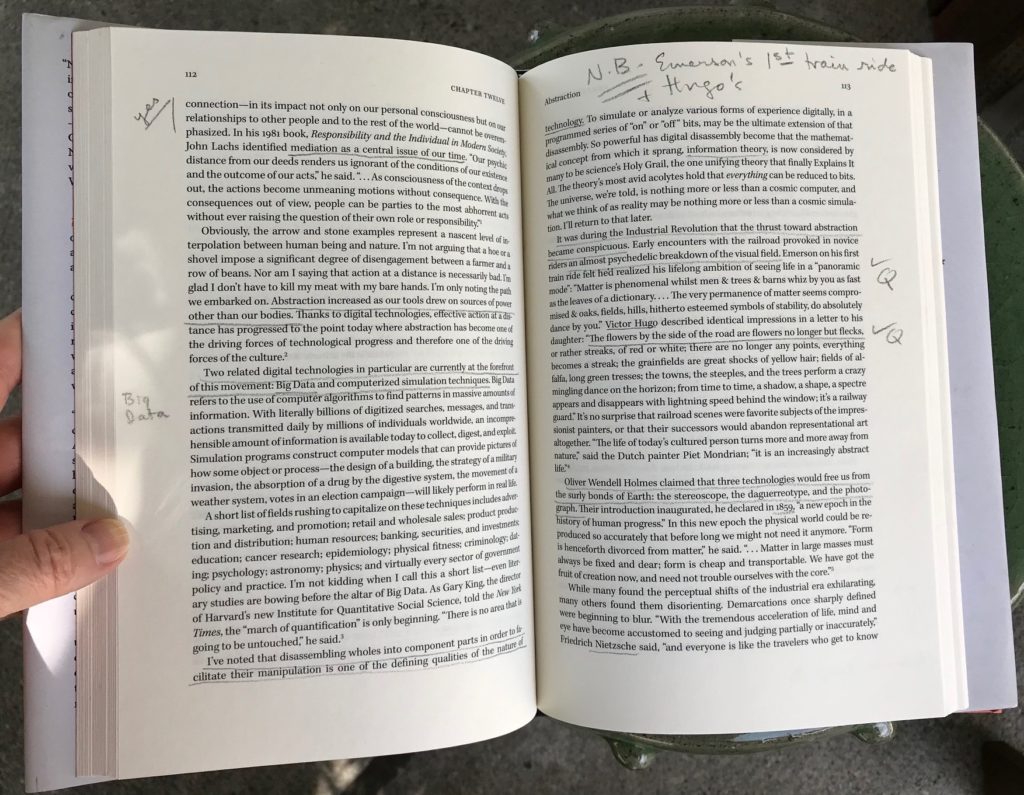

Katherine Dunn: On the Brink of Everything by Parker Palmer, Two Prospectors, the collected of letters between Sam Shepherd and Johnny Dark.

C.M. MAYO: How has the Digital Revolution affected your writing and your art? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused on artistic endeavors with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

Katherine Dunn: Well…I could not do what I do, as a freelancer since 1996, out in the country without it. I think it is the political and chaos we are in as a nation that is more distracting right now. I have an iPhone that I use mainly for photos…but I’m not attached to it like many people. I have learned to sit down, and state in my head what I need to do, i.e., “I need to get this canvas started and work on it for one hour.”

Simple tiny steps of work. I find I actually get a lot done in a shorter amount of time than when I was younger.

I also do not feel compelled to be in the studio all the time. I’m 62, maybe that is part of it–I have less enthusiasm for other people’s presence.

I think if most people just tried off notifications on their iPhones it would help! I see some people unable to have a 5 minute conversation without getting interrupted.

I’ve learned to get on and off social media. I deleted 5000 “friends” on Facebook and kept 100 of people I really knew. I never post on it. I only maintain my Apifera Farm nonprofit page. I don’t comment hardly ever on anything of FB. I decided it was a drain and that I was basically entertaining the masses with free photos, stories and more, and was not seeing a return. The nonprofit still can bring in donations through FB. Instagram is eye candy, I use it as a marketing tool for my non profit, and post art when I have it to show.

But that’s it. I don’t interact on it, except to see a baby photo or something of real friends.

C.M. MAYO: Another question apropos of the Digital Revolution. As a writer, at what point were you working on paper? Was working on paper necessary for you or problematic?

Katherine Dunn: I kind of worked on paper, and still do, if I’m creating a book, because I am so visual. Especially if it is an illustrated book. I need to see thumbnails over and over as it evolves. but I don’t write on paper. All my books, I think there are 6, were always typed on the computer…I keep lists and ideas here and there, but I work on the computer.

C.M. MAYO: For those looking to publish, what would be your most hard-earned piece of advice?

Katherine Dunn: Oh man….

If you are looking to publish with a publisher…I don’t even know what to say because of my experience. I hired a former editor of Chronicle books back in 2010 when I was working on what was then called Raggedy Love but became Donkey Dreams. He helped enormously. He helped me learn the importance of shaping a book, editing, etc. And focusing. He would keep the story on track…it was so helpful. Especially in today’s worlds of blogs–some peoples’ books just feel like blogs. Anyway, it was one of the best investments I made. And we really thought we had a book, and he pitched it to about 15 places.

Illustrated memoir is hard to place. It was disappointing. That is when I first self-published about a year later. I did publish with a publisher for a how-to-art-inspiration book back in 2008 or there about, it was a good lesson on how a book comes together.

Self-publishing is rewarding and cost effective. But lots of work. I use offset printers, more cost effective but also more upfront money.

To be honest, I got so sick and tired of sending query letters that went unanswered, or had no feedback…or got good feedback and then…silence. I just got tired of it. Same things with agents.

I like being my own band. Life is too short.

On the other hand, if you have a connection with someone, that makes all the difference in the world. But my days of having connections like that are over, and I am fine with that.

C.M. MAYO: What important piece of advice would you give yourself if you could travel back in time ten years?

Katherine Dunn: hmmm….I think I lived as I wanted, and still do, so don’t think I have any advice like that…

Maybe …. “It will be okay.”

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you?

Katherine Dunn: Good question. I still want to market White Dog more, it came out during Covid. So I am percolating that.

I had a stretch of good painting, large canvases for Sundance which was a nice change.

I have some creatures warranting books or something…The Goose, Walter the cat…I don’t know…

I have to tell you, the world situation is very upsetting. So I’m letting myself do what feels right at the moment of each day.

Visit Katherine Dunn at www.katherinedunn.com. You can order a copy of White Dog here.

Q & A with Poet Barbara Crooker on the Magic of VCCA,

Reading, and Some Glad Morning

Q & A with Bruce Berger on A Desert Harvest

The Marfa Mondays Podcast is Back! No. 21:

“Great Power in One: Miss Charles Emily Wilson”

#

Find out more about

C.M. Mayo’s books, articles, podcasts, and more.