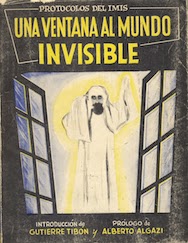

Una ventana al mundo invisible. Protocolos del IMIS

Editorial Antorcha, Mexico City, 1960.

[A Window to the Invisible world: Protocols of the IMIS]

I was a long ways into into the labyrinth of research and reading for my book, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution, when I happened into Mexico City’s Librería Madero, expressing a vague interest in Francisco I. Madero and “lo que sea de lo esotérico.” When the owner, Don Enrique Fuentes Castilla, set this book upon the counter, I confess, the cover, which looks like a Halloween cartoon, with such childish fonts, did little to excite my interest. But oh, ho ho (in the voice of the Jolly Green Giant):

This book, Una ventana al mundo invisible, is nothing less than the official, meticulously documented records of the dozens and dozens of research-séances of the Instituto Mexicano de Investigaciones Síquicas or IMIS (Mexican Institute of Psychic Research) from April 10, 1940 to April 12, 1952, members of which included– the book lists their names and their signatures— several medical doctors and National University (UNAM) professors; an ex-Rector of the UNAM, the medical doctor and historian Dr. Fernando Ocaranza; several generals; ambassadors; bankers; artists and writers, including José Juan Tablada; a supreme court justice; an ex-Minister of Foreign relations; an ex-director of Banco de México, Carlos Novoa; Ambassador Ramón Beteta, ex Minister of Finance; and… drumroll… both Miguel Alemán and Plutarco Elías Calles. *

*I hate giving wikipedia links but as of this writing, the official webpage for the Mexican presidency doesn’t go back more than four administrations.

For those a little foggy on their Mexican history, Plutarco Elías Calles served as Mexico’s President from 1924-1928, and Miguel Alemán, 1946-1952. At the time of the séances documented in Una ventana al mundo invisible, Calles was in retirement, having returned from the exile imposed on him by President Cardenás in the 1930s.

When Una ventana al mundo invisible was published in 1960, Alemán was long gone from power, and Calles had passed away.

I had heard, as has anyone who goes any ways into the subject, that Alemán and Calles and other Mexican “public figures” were secret Spiritists, but here, dear readers, in the Protocolos del IMIS, are the smoking signatures.

Yes, There are Other References to

Una ventana al mundo invisible

Mexican historian Enrique Krauze was one of the first to cite Una ventana al mundo invisible in his chapter on Calles in Biography of Power, as does Jurgen Burchenau in his biography, Plutarco Elías Calles and the Mexican Revolution. But, as I write these lines, Una ventana al mundo invisible remains surprisingly obscure.

Of course, I googled. A Mexican writer, Héctor de Mauleón, had discovered Una ventana al mundo invisible in a different Mexico City antiquarian bookstore and written up a summary for the October 2012 issue of Nexos. (But he complains of his copy’s missing the picture of the conjured spirit, “Master Amajur.” More about that in a moment.) And also recently, Grupo Espírita de la Palma, a Canary Islands Spiritist blog, which has posted several important bibliographic notes as well as a bibliography of Spanish works on Spiritism, posted this piece about the Jesuit Father Heredia’s involvement with the IMIS–thanks to his friend, none other than Calles–and about this book.

How about WordCat? Yes, there are several copies of the 1960 edition of Una ventana al mundo invisible in libraries in Mexico City. And three copies in the United States: the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, and (why?) the University of West Georgia. Ah, and WorldCat also shows several copies in Mexico of an edition © 1993 and published in 1994 by Planeta and another, expanded edition published by Posadas in 1979.

(A research project for whomever wants it: to delve into the Mexican hemerotecas of 1960-61 for any newspaper coverage, and 1979 and 1994 for anything about the Posadas and Planeta editions. My guess is, not much, for the press was largely under the thumb of the ruling party and this sort of information about Mexican Presidents would have been, to say the least, unwelcome. But that’s just my guess.)

So, Now, Delving into the Contents…

The copy Don Enrique was offering, and for a very reasonable price, still had its dust jacket, small tears in places along the bottom and the top, but intact (the image on this blog post is a scan of my copy). The rest of it was pristine; the pages had not even been cut. Don Enrique slit open a few for me in the bookstore, and once home, I continued with my trusty steak knife (read about my other steak knife adventure here.)

I dove right in and learned that the founder of the IMIS, to whose memory the book is dedicated, was Rafael Alvarez y Alvarez (1887-1955), a distinguished Mexican banker, a president of the Monte de Piedad, and a congressman and senator. (Looking at his portrait with my novelist’s eye– that gaze! the bow tie!– yes, the intrepid maverick.)

The introduction is by Gutierre Tibón, an Italian-Mexican historian and anthropologist, professor in the National University’s prestigious faculty of Philosophy and Literature, and author of numerous noted works, including Iniciación al budismo and El jade de México.

A Brief Bit of Background

on 19th Century Parapsychological Research

The goal of the IMIS was to progress in the tradition of pioneer American, English, and European parapsychological researchers. From my book, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution, the first chapter, which provides 19th century background for Madero’s ideas about Spiritism, which he considered both a religion and a science:

“The exploits of mediums such as the Fox sisters, D.D. Home, the Eddy Brothers, and later in the nineteenth century, prim Leonora Piper (channel for the long-dead “Dr Phinuit” and the mysterious “Imperator”), and wild Eusapia Palladino (whose séances featured billowing curtains, floating mandolins and, popping out of the dark, ectoplasmic hands), spurred the studies of investigators, journalists and a small group of elite scientists. Noted German, Italian, and French scientists, such as Nobel prize-winning physiologist Charles Richet undertook the examination of these anomalous phenomena, but the British Society for Psychical Research, founded in 1882, and the American Society for Psychical Research founded three years later, led the fray. Though their ranks included leading scientists such as chemist William Crookes, naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, physicist Oliver Lodge, and William James (the Harvard University professor considered the father of psychology). Yet their researches almost invariably met not with celebration, nor curiosity on the part of their fellow academics, but ridicule, often to the point of personal slander.”

On that note, for anyone interested in learning more about 19th century parapsychological research, a very weird swamp indeed, I recommend starting with science journalist Denorah Blum’s excellent Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death. (See also Blum’s website.)

Medium Luís Martínez

and “Spirit Guide” Dr. Enrique del Castillo

As James et al had Leonora Piper, and Richet and Lombroso, Eusapia Palladino, the IMIS employed the medium Luis Martínez, who was able to evoke a broad spectrum of phenomena, from ringing bells to apports, ectoplasm, breezes, raps and knocks, levitation, and so on.

In séances with Martínez, the IMIS heard from its spirit guide on the “other side,” one Dr. Enrique del Castillo, a Mexican doctor of the 19th century. According to Dr Tibón in his introduction to Una ventana al mundo invisible (p. 20, my translation):

“The way he looked was perfectly well known because once he “aported” his photograph, which was later made into a larger size, framed and displayed the Institute’s workroom. Another aport of Dr. del Castillo were his spectacles, identical to those in the portrait. He brought them on October 24, 1944, at 10:30 pm, in a séance that was documented in Cuernavaca, and he said these words, directing them to Rafael Alvarez y Alvarez: ‘In leaving my spectacles to you, dear son, it is with the wish that you will see clearly the future road we must take. May these spectacles take you on the path where we will always be companions.'”

Enter “Master Amajur”

Of special note was the séance on the evening of September 24, 1941, when Plutarco Elías Calles invited Carlos de Heredia, S.J., author of a book debunking Spiritism– and Father Heredia, sufficiently awed (and according to Calles, converted) affixed his signature as witness to genuine phenomena. That séance is documented in its entirety in Una ventana al mundo invisible. From Dr. Tibón’s introduction (p.21, my translation):

“That memorable night there materialized another spirit guide for the circle: an oriental doctor named Master Amajur; and he did not only show himself completely to Father Heredia, he also spilled a glass of water, saturated it with magnetic fluid, and gave it to him to drink. Then there appeared the phantom of Sister María de Jesús and, before the astonished cleric, illuminated her face in a most unusual manner. Finally, Dr Enrique del Castillo appeared, surrounded by many tiny lights. These levitated the medium, chair and all– the equivalent of raising almost 100 kilos– and silently left him in the other end of the room. This phenomenon was verified for the first time. Later, I had the fortune to attend its repetition and I literally saw the medium fly two meters into the air.”

Master Amajur started showing up from the first documented séance of May 8, 1940 (p. 89, my translation of some of the highlights):

“Master Amajur [appeared] very clearly, he touched all of us and he wrote a message which says: Go forward and I will help you. When we asked him [for a message] he left a message for Colonel Villanueva that says: It would be good for you to attend a séance. [… ]The first materialization produced an electric spark above the lightbulb that was loose in its socket[… ] There was an aport: a small bottle of perfume and its essence sprinkled above us. The music box passed over our heads. The Master gave us his cloak to touch, which seemed to all of us a piece of gauze. One again he produced a fresh breeze: it smelled of ozone.

On June 12, 1940 (p.90, my translation):

[…] the Master came in. This manifestation appeared first as a human hand covered with a veil, imitating a human figure. Then it increased in size and luminosity until it came txo a height of about 1.5 meters. Only the head and bust could only be seen. It was covered in a bluish white veil which I touched with my face. It gave me the impression of being a cotton fabric… It gave me a large glass of water to drink… It put flowers in our hands, it gave us a perfumed air, and when luminous blobs passed near my face I perceived the smell of phosphorous.”

On June 22, 1941 (my translation, p. 92):

“In front of all of us, Amajur left on the wall an inscription that said: Go forward. Upon request, he gave fluid to a magnolia and then he began to cut the petals. One by one these were deposited in the mouths of the participants.”

And so on. Séance after séance after séance–96 in all–with sparks, music, levitations, ectoplasmic this & that, perfumes, flowers, and frequent appearances not only by Master Amajur and sundry others, but also a childlike spirit, “Botitas” (Little Boots), who would tug on the participants’ pant legs.

Photographing Master Amajur

Skipping ahead to the séance of June 17, 1943– which Plutarco Elías Calles attended– Master Amajur has agreed to pose for a photograph. At first this doesn’t work; the photographer only captures a hand and then, suddenly, falls into convulsions. But then, after some further bizarre phenomena and friendly intervention by the spirit Dr. del Castillo, the photograph is achieved (p. 194, my translation):

“According to Mrs. Padilla [wife of Ezequiel Padilla, ex Minister of Foreign Relations, also in attendance on this occasion], and in agreement with all the other participants, at the moment of the explosion or flash from the photographer’s lamp, in the shadow could be seen the complete figure of the master, as if a statue of about 2 meters covered in a cloak, from head to foot. It was also noted that Master Amajur received a powerful shock and on asking him if he would permit another photograph to be taken, he said no.”

According to the dust jacket flap text, this is the very photograph that adorns the cover of the book. But, um, it looks more like a drawing to me. (As, by the way, many purported “spirit photographs” do. Google, dear reader, and ye shall find. Lots on eBay, by the way.)

For historians of the metaphysical, it is interesting to note that Master Amajur claimed to be a member of the Great White Brotherhood, a term which came into use in the West with Madame Blavatsky, co-founder of the Theosophical Society, in the 19th century. She claimed that her teachers, who often met with her on the astral plane, were the Great White Brothers or Mahatamas, the Ascended Masters Koot-hoomi (Kuthumi) and Morya. Later, her follower A. P. Sinnett expanded on this topic in a sensational book of its day, The Mahatma Letters (1923). Over the decades, other psychics claimed to receive channeled messages from various Ascended Masters, most notably “St. Germain” and Alice Bailey’s “Djwahl Khul” or “The Tibetan.” It would seem that “Master Amajur” falls into this rather blurry and ever-morphing category.*

*So are the terms Great White Brother, Mahatma, and Ascended Master one and the same? In this article in Quest, modern-day Theosophist Pablo B. Sender elucidates.

Interesting to note also that a google search brought up the tidbit that “Amajur” was the name of an astronomer of 10th century Baghdad– though I hasten to add, according to the IMIS reports in Una ventana al mundo invisible, “Master Amajur” spoke Mexican Spanish. And of further note: there are Spiritist groups that continue to channel messages from Master Amajur today.

Dear readers, conclude what you will, and whether this finds you embracing a gnosis that “resonates” with you, cackling like a hyena, or just numbly confused, surely we can agree that this is all very remarkable.

So What, Pray Tell, Does All This Have to Do

with Don Francisco I. Madero?

My book, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution, is about Madero as leader of the 1910 Revolution and President of Mexico, 1911-1913 and how his political career was launched as an integral part of his Spiritist beliefs. (The book includes my translation of his secret book of 1911, Spiritist Manual, which spells it all out– all the way to out-of-body travel and, yes, interplanetary reincarnation.)

Not all– Enrique Krauze, Yolia Tortolero Cervantes, Javier Garciadiego, Alejandro Rosas Robles, Manuel Guerra de Luna, among others, are important exceptions– but most historians of Mexico and its Revolution sidestep, belittle, or even ignore Madero’s Spiritist beliefs. In my book, I have quite a bit to say about why I think that is (key words: cognitive dissonance), but in sum, few have any context for Madero’s ideas which, for most educated people in the western world, fall into the category of absurd nonsense and “superstition.”

My aim in my book– and this blog post– is not to convince the reader of the truth or falsity of any religious beliefs (ha, neither do I poke tigers with sticks for the hell of it), but to provide a sense of the history and richness of the matrix of metaphysical traditions from which Madero’s beliefs emerged. And with this context, I believe, we can arrive at the conclusion that Madero was not mad, nor so naive and weak as many have painted him, but that, in fact, he was a political visionary of immense courage who found himself on a counterrevolutionary battlefield of such rage and chaos that, if it was fatal for him, would have been for almost anyone else as well.

Madero did not, like some mad alchemist, cook up his ideas by himself; they fit into what was then and is now a living tradition. Madero’s Spiritism was French, itself an off-shoot of American Spiritualism, and with roots in occult Masonry and hermeticism and mesmerism; in the early 20th century, Madero also adopted ideas from a wide range of difficult-to-categorize mystics, such as Edouard Schuré, and from the Hindu holy book so beloved of the Theosophists, Thoreau, and Mohandis Gandhi: the Baghavad-Gita.

After Madero, on the one hand, we see Spiritism melding with folkloric and shamanistic traditions, as with the mediumistic healers Niño Fidencio, Doña Pachita, and the “psychic surgeons” of Brazil and the Philippines. On the other hand, a very small and adventurous group of what was primarily members of the educated urban elite– as we see in Una ventana al mundo invisible– continued the international tradition of parapsychological research that, as we know from his Spiritist Manual and his personal library, Madero greatly admired.

Relevant Links:

>My book, now in paperback and Kindle:

Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution:Francisco I. Madero and His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual

>En español (Kindle):

Odisea metafísica hacia la Revolución Mexicana.Francisco I. Madero y su libro secreto, Manual espírita

>Resources for Researchers: Blogs, Articles, and More

>Mexico City’s incomparable Librería Madero

Why Translate? The Case of the President of Mexico’s Secret Book

A Visit to El Paso’s “The Equestrian”

#

Find out more about

C.M. Mayo’s books, articles, podcasts, and more.