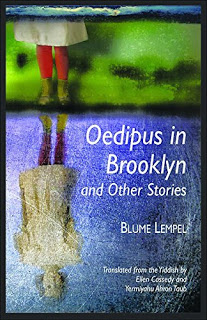

Strange, muscled, riven with grief, Blume Lempel’s short stories, many set in the U.S., are for the ages. Yet because Lempel wrote in Yiddish, few aficionados of the form have had the chance to read her— until now, with the translation by Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub, Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories.

Excerpts from the catalog copy of the publishers, Dryad Press and Mandel Vilar:

“Lempel (1907–1999) was one of a small number of writers in the United States who wrote in Yiddish into the 1990s. Though many of her stories opened a window on the Old World and the Holocaust, she did not confine herself to these landscapes or themes. She often wrote about the margins of society, and about subjects considered untouchable. Her prize-winning fiction is remarkable for its psychological acuity, its unflinching examination of erotic themes and gender relations, and its technical virtuosity. Mirroring the dislocation of mostly women protagonists, her stories move between present and past, Old World and New, dream and reality…

“Immigrating to New York when Hitler rose to power, Blume Lempel began publishing her short stories in 1945. By the 1970s her work had become known throughout the Yiddish literary world. When she died in 1999, the Yiddish paper Forverts wrote: ‘Yiddish literature has lost one of its most remarkable women writers.'”

Ellen Cassedy, translator, is author of the award-winning study We Are Here, about the Lithuanian Holocaust. With her colleague Yermiyahu Ahron Taub, they received the Yiddish Book Center 2012 Translation Prize for translating Blume Lempel.

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub is the author of several books of poetry, including Prayers of a Heretic/Tfiles fun an apikoyres (2013), Uncle Feygele (2011), and What Stillness Illuminated/Vos shtilkayt hot baloykhtn (2008).

C.M. MAYO: Can you tell us more about Yiddish as a language, and specifically, its roots and connections with other languages, including German and Ladino?

ELLEN CASSEDY & YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: Yiddish is a Germanic language written in the Hebrew alphabet. For hundreds of years, it was the everyday vernacular spoken by Jews in Eastern Europe. While Ladino became the Spanish-inflected language of Jews in the Mediterranean region, Yiddish was the everyday language among Jews living farther north, in Germany, Russia, and Eastern Europe.

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: There is an alternative theory that Yiddish is essentially a Slavic language, but most scholars believe it’s a Germanic language.

ELLEN CASSEDY: For me, Yiddish is a holy tongue. Translating Yiddish connects me to a history, an enduring cultural legacy. Yiddish is precious to me for its outsider point of view, its irony, its humor, its solidarity with the little guy, its honoring of the everyday.

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: The Yiddish language has been a crucial tool for my literary work. As a bridge to the past and an enhancement of my literary and social present, Yiddish opens a vibrant linguistic plane, full of texture, play, and reference. Yiddish is for me a place of primal connection and, for all its and my “baggage,” a source of strange comfort. Writing, reading, and translating Yiddish also allows me to learn new Yiddish words and re-learn forgotten ones.

C.M. MAYO: You write in the introduction that for Blume Lempel the “decision to write in Yiddish was a carefully considered choice.” What do you think motivated her to write for what was already a quickly shrinking readership?

ELLEN CASSEDY & YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: For Lempel, Yiddish was a portable homeland that served her well as she encountered new circumstances and new languages. Born in 1907 in a small town in Eastern Europe, she immigrated to Paris and then fled to New York with her family just before World War II. Until her death in 1999, writing in Yiddish enabled her to express her connection to those who had perished in the Holocaust – as she put it, to “speak for those who could no longer speak.”

Writing in Yiddish also afforded a kind of “privacy.” Lempel wrote about subjects considered taboo by other writers – abor—ion, rap—, erot— imaginings, even inc—st.* Would she have felt free to exercise the same artistic freedom in English? Perhaps not.

*[C.M.: Massive apologies for inserting these ridiculous dashes but if left in plain English, which I am sure that you, gentle reader, can figure out, the Google bot may, in the Byzantine wisdom of its algorithms, send this blog into SEO netherworlds.]

But if Lempel needed privacy for artistic freedom, she also wanted recognition and worked hard to get her work out to a wider audience. Her efforts paid off. Over the years, she won widespread admiration among Yiddish writers and readers and received numerous Yiddish literary prizes.

C.M. MAYO: What do you think would have been lost in these stories had Lempel written in English? This is another way of asking, what were the biggest challenges for you as translators?

ELLEN CASSEDY: I don’t put much stock in the idea that some literary qualities can be expressed only in their original language. For me, what’s important is the fluidity and freedom that Lempel herself experienced, which resulted in the extraordinary richness of her prose. I’m not sure she could have attained such heights in a language that was not part of her very being from girlhood on.

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: As we translated, we encountered surprises at every turn—in virtually every paragraph, and on every page. Lempel’s prose is so poetic and rich that we had to exercise special care to capture her unique melody.

Sometimes we had to accept uncertainty, realizing we wouldn’t be completely certain of Lempel’s meaning even if her text had been written in English. It was immensely satisfying to work with a partner, to be able to bounce ideas off each other, and to know that our interchange would strengthen the final version.

ELLEN CASSEDY: Lempel’s narrations move between past and present, often several places on the same page, from Old World to New, from fantasy to reality. Imagine the conversational matter-of-factness of a Grace Paley combined with the surreal flights of a Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

C.M. MAYO: Can you also talk about how it was to work together as co-translators?

ELLEN CASSEDY: Working together was a joy. Once we’d selected the stories, each of us chose our favorites and produced first drafts. Then the other one carefully went over those drafts and made suggestions.

I was brought up to pay very close attention to the wonders of the English language. Every family dinner included at least one trip to the dictionary. I brought that intense involvement with English to the translation table.

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: Working together has been joyful, yes… but also humbling. One had to be open to another’s suggestions and feedback throughout the process. There was a lot of give and take, back and forth about meaning, the best turn of phrase, etc. Of course, every book, even one by a single author (and no translators), is a collaboration of some kind—with the publisher, editor, cover artist, designer, etc. But collaboration on the text— of every word of it—is much more so. I’ve learned a great deal from this process—about translation, about myself … and about Ellen!

Of course, this collaboration is still an ongoing process, as we complete interviews and embark on speaking engagements on behalf of the book. I feel so fortunate to be working with Ellen.

ELLEN CASSEDY: Back at you, dear partner!

C.M. MAYO: Do you think Lempel’s visibility as a literary artist, and her life, might have been different had she written in English?

ELLEN CASSEDY & YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: Absolutely. The Yiddish literary circle after World War II was far-flung but cohesive, and she thrived within it. Yiddish publications all over the world carried her work. She received prizes in Israel, Canada, and the U.S. When she died, the Yiddish paper Forverts wrote: “Yiddish literature has lost one of its most remarkable women writers.”

Despite her success within the Yiddish literary sphere, though, she always dreamed of an English-language readership. Although a few individual stories of hers appeared in journals and anthologies, there has been no full-length collection in English until now. It’s a joy for us to help her unrealized dream come true.

C.M. MAYO: What inspired you to translate Yiddish?

ELLEN CASSEDY: Years ago, when my Jewish mother died, I decided to study Yiddish as a memorial to her and a way to sustain ties with my Jewish forebears on both sides of the Atlantic. I was also looking for a home within Jewish culture, and I hoped Yiddish language and literature would provide that home. And indeed it has!

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: Yiddish was a part of the ultra-Orthodox yeshiva world in which I was raised. I studied it formally as an adult and have been engaged in Yiddish culture since the early 1990’s.

C.M. MAYO: What brought you to translate Blume Lempel?

ELLEN CASSEDY: Early on, when I told my Yiddish teacher I wanted to try my hand at translation, he went to his bookshelf and pulled out a little volume– Blume Lempel’s first collection, personally inscribed to him by the author. When I met Yermiyahu Ahron Taub in a Yiddish reading group, we decided to look into this volume. We were astounded to find truly unique writer with a dazzling lyrical style, an unparalleled compassion for her characters, a startling diversity of settings, and a daring range of subjects.

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: It didn’t take long for us to decide we had to translate these splendid stories so that they could reach the wider audience they so richly deserve.

C.M. MAYO: If you could select one short story as the most representative of her work, which one would it be, and why?

ELLEN CASSEDY: It’s hard to choose, because Lempel’s range of settings and characters is huge. She tells truths about women’s inner lives that I’ve never encountered anywhere else.

“Waiting for the Ragman” is particularly rich in its description of life in a small Eastern European hometown, including a loving description of preparation for the Sabbath.

And I have to mention the title story, “Oedipus in Brooklyn.” Lempel masterfully draws you into the story of a contemporary Jewish mother and her blind son as they move inexorably toward their doom.

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: “Her Last Dance” tells the story of a Jewish woman forced to rely on her wits and beauty to survive wartime Paris. Despite its small scale, it evokes for me the work of Irène Nemirovsky and Nella Larsen (Passing). In capturing the desperation of a woman on the edge, it reminds me of Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth.

“The Invented Brother” captures the poignant emotions of a young girl whose beloved older brother is swept away into revolutionary activity.

C.M. MAYO: In one of the many blurbs for this collection, Cynthia Ozick calls Blume Lempel “a brilliantly robust Yiddish-American writer. Why should Isaac Bashevis Singer and Chaim Grade monopolize this rich literary genre?”

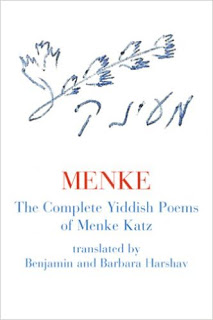

Can you tell us more about some of the writers Blume Lempel would have been reading and corresponding with in Yiddish? (Did she know Menke Katz?)

ELLEN CASSEDY & YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: Avrom Sutzkever, the “dean” of postwar Yiddish poetry, was an admirer, and a mentor. She was admired by other leading Yiddish writers as well, including Yonia Fain, Chaim Grade, Malka Heifetz-Tussman, Chava Rosenfarb, and Osher Jaime Schuchinski.

And yes, she did know the New York poet Menke Katz. We found several warm letters from him within her papers.

C.M. MAYO: Of those writers not writing in Yiddish, which were important influences for Lempel?

ELLEN CASSEDY & YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: She was one of a kind. When an interviewer asked which writers had influenced her, she mentioned Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, and the philosophers Spinoza and Bergson, but only in passing. She didn’t feel part of any school or tendency.

The key to reading this amazing writer is to approach her work without preconceived expectations of what fiction should be. Open yourself up to the twists and turns, the possibilities. You’re in for a wild and wonderful ride.

C.M. MAYO: How do you see the future of Yiddish?

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: That’s a big question. Yiddish is still the lingua franca of various Hasidic communities in Israel and the Diaspora. One can see Yiddish signs, for example, in Monroe, N.Y., Monsey, N.Y., and Williamsburg, Brooklyn, among numerous other places. Of course, Hebrew encroaches in Israel, and English encroaches in the United States. Still, I don’t foresee Yiddish fading away in those communities any time soon. Hasidic communities believe in Yiddish as a bulwark against the encroaching “dominant” culture.

In terms of secular Yiddish culture, a small number of families are committed to raising their children in Yiddish. And there is considerable artistic and intellectual activity in the realm of Yiddish culture – panels on Yiddish at Association for Jewish Studies conferences, concerts, gatherings, and festivals dedicated to Yiddish, and releases of books and compact discs.

Translation is a particularly rich area of contemporary Yiddish culture. A recent anthology called Have I Got a Story for You: More Than a Century of Fiction from the Forward (Norton, 2016), edited by Ezra Glinter, demonstrates the work of numerous Yiddish translators active today. Of course, some would argue that that itself is a sign of demise. I don’t see it that way. Translation requires knowledge of both linguistic contexts.

Do I think all of this qualifies as a rebirth? Not exactly, but nor do I see Yiddish as dead, dying, or even endangered really.

C.M. MAYO: Have Lempel’s stories had an influence on you as a writer, and if so, how?

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: It’s hard to know if Lempel’s stories have influenced me as a writer or if I was drawn to her because of my pre-existing interests. Certainly, we both share an interest in the realms of the marginal and the “outsider,” although we might have differing perceptions of who is marginal or an outsider. We also share an interest in poetry and poetic language, and the blurring of the line between poetry and prose. I certainly consider Blume Lempel to be a kindred writerly spirit and an inspiration.

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you as writers and translators?

ELLEN CASSEDY: I’m currently seeking a publisher for my translation of fiction by the Yiddish writer Yenta Mash, who grew up in Eastern Europe not far from Blume Lempel. I’m excited to have won a PEN/Heim translation grant – the first ever for a Yiddish book – to support this work.

YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: A new collection of my poems is currently in the publication process. Six of the poems also have a Yiddish version, which raises all sorts of translation and design challenges.

ELLEN CASSEDY & YERMIYAHU AHRON TAUB: And of course we’re getting the word out about the Blume Lempel collection. It’s exciting to introduce English-language readers to these stories with their dazzling prose and their bold approach to storytelling.

Visit Ellen Cassedy at her webpage here.

Visit Yermiyahu Ahron Taub at his website here.

P.S. Philip K. Jason gives Oedipus in Brooklyn a rave review in The Washington Review of Books.

And if you’re in the Washington DC area, don’t miss the launch at Politics & Prose Bookstore:

Sunday, January 8, 1 pm

Politics & Prose Bookstore

5015 Connecticut Ave NW

Washington, DC 20008

The event is free with no reservation required.

Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories by Blume Lempel

Translated by Ellen Cassedy & Yermiyahu Ahron Taub

Mandel Vilar Press & Dryad Press, 2016

Q & A: Yermiyahu Ahron Taub on Prodigal Children in the House of G-d

Q & A: Nancy Peacock on The Life and Times of Persimmon Wilson

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.