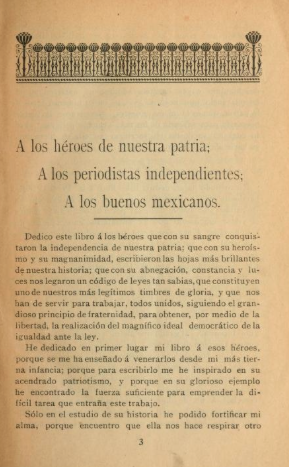

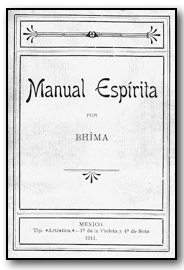

The astonishing thing about Francisco I. Madero’s Manual espírita of 1911 is that it lays out his philosophy so passionately and precisely, and yet, with counted exceptions (among them, Mexican historians Tortolero, Guerra de Luna, and Rosas), apart from cursory mentions, historians have told us nearly nothing about this text, its origins, broader esoteric cultural context, and profound implications for understanding Madero’s actions as leader of the 1910 Revolution and as President of Mexico. My translation of Madero’s Manual espírita— the first into English and, as far as I have been able to ascertain, into any language— is included in my book, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual.

>>Click here to view a one minute-long Mexican government video which gives a very basic idea of the official version of Madero’s importance in Mexico.<<

Madero was a medium in the Spiritist tradition of the late 19th and early 20th centuries of France and Mexico. While Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution is a scholarly contribution, I write about Madero and his Spiritist Manual not as an academic historian, but as his translator and as a creative writer who has lived in and written about Mexico for many years. I presumed that most of my readers would encounter Madero’s ideas about communicating with the dead extremely peculiar, even disturbing. For the most part this has been the case. To give one of several (to me, amusing) examples, one prominent Mexico expert who shall remain unnamed felt moved to inform me that, though he very much enjoyed my book, he would not be reading Spiritist Manual.

That said, I am grateful to have been invited to speak about it at the Centro de Estudios de la Historia de México CARSO, Mexico City’s National Palace, Rice University, Stanford University, UCSD Center for US-Mexican Studies, and elsewhere, and to date, historians of Mexico and other scholars in these audiences have been both thoughtful and generous in their comments.

To my surprise, however, the Internet has brought my and Madero’s books another, very different audience, one that encounters the Spiritist Manual as, shall we say, a vintage text out of a well-known and warmly embraced tradition.

In his review for the National Spiritualist, Rev. Stephen A. Hermann writes, “Anyone interested in the history of international Spiritualism as well as as mediumnistic unfoldment will find this manual invaluable.”

With the aim of providing further historical and philosophical context for Francisco I. Madero and his Spiritist Manual, I asked Rev. Hermann if, from the perspective of a practicing medium and teacher of mediumship— and author of the just-published Mediumship Mastery: The Mechanics of Receiving Spirit Communications— he would be so kind as to answer some of my questions about Madero as a medium and about his philosophy.

ON MADERO AS MEDIUM

C.M. MAYO: In your book, Mediumship Mastery, you distinguish between two broad types of mediumship, mental and physical. “Automatic writing” you categorize as both. Francisco I. Madero was a writing medium, that is, a medium who channeled messages from the spirit world through his hand and pen onto paper. Can you explain this? And, is this type of mediumship still common today?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: Madero practiced automatic writing in which spirit personalities would control the movements of his arm and hand to write messages. It is common for many people, not knowing the difference, to confuse automatic writing with the phase of mediumship known as inspirational writing. With inspirational writing the medium’s conscious and unconscious mind are very much involved with the process. Genuine automatic writing occurs typically quite rapidly with the medium unable to control the movements taking place. The conscious mind of the medium is not involved in the process and the medium could even be engaged in a conversation with others while the writing is produced.

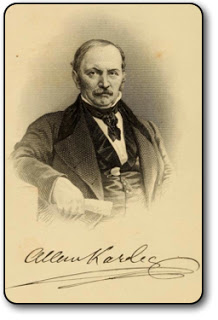

In the period that Madero developed his mediumship the practice of automatic writing, the use of planchette and table for spirit communication was quite common for many mediums. Madero was heavily influenced by the writings of the French Spiritualist Kardec, whose classic Medium’s Book was widely used by students of spirit communication as a standard for mediumistic unfoldment.

As a phase of mediumship automatic writing is not commonly practiced the way it would have been a century ago. In most countries around the world most mediums practice mental phases of mediumship such as clairvoyance, clairaudience and clairsentience (psychic seeing, hearing and sensing). There are also many mediums who practice controlled speaking or trance channeling.

C.M. MAYO: How how would you, as a medium, evaluate Madero’s mediumnistic notebooks? (These are preserved in his archive in Mexico’s Ministry of Finance; in my book, I quoted from some of them, communications in Madero’s handwriting signed by “Raúl,” “José” and “B.J.”).

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: I was impressed by Madero’s dedication to God, the spirit world and his mission to help Mexico. He certainly appears to have lived by higher spiritual principles. The communications that he received I feel were genuine and indicate the great effort of teachers in the spirit world to use him as a positive influence in the material world. I would love to see all his notebooks published and your book distributed even more as Madero’s work is an excellent example of a politician motivated selflessly out of love and duty.

[C.M. MAYO: The mediumnistic notebooks have been transcribed and published in volume VI. of Obras completas de Francisco Ignacio Madero, edited by Alejandro Rosas Robles, Editorial Clío, Mexico, 2000. For more about the work of Alejandro Rosas Robles and other Mexican historians on Madero and esoteric philosophy, see my post Lifting the (Very Heavy) Curtain on the Leader of Mexico’s 1910 Revolution].

C.M. MAYO: It seems that by the time Madero became president he was no longer channeling written messages but instead relied on “inspiration” or telepathic communication from spirits. My understanding is that Madero considered this an advance in his mediumnistic abilities. Would you agree?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: A student of mediumship is always progressing and as such the manner that his or her mediumship functions will evolve accordingly. I assume that Madero would have put considerable effort into growing as an individual as well as enhancing his own mediumistic skills. It is not that one phase of mediumship is better than another. All spiritual gifts are ways for the spirit personalities to bring love and healing to people in the material world. It is very common for mediums to develop new phases of mediumship as they gain experience and are ready. Madero was very progressive in all aspects of his life.

C.M. MAYO: One of the questions I invariably hear in any presentation or conference about Madero and his Spiritism is that, if he really were hearing from spirits, why did they not warn him about the coup d’etat of 1913, so that he could save himself? (Perhaps because as President coping with the challenges of governing, he no longer had the peace of mind to listen?) In Mediumship Mastery (p. 154-155) you write, “While warnings might be given in order to prevent a mishap, telling the recipient negative information such as he or she is going to die next week or be involved in a serious accident, generally would not come through with controlled regulated mediumship.” Can you explain and/or elaborate?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: Madero would have been under great stress so it is very possible that his own mind would not have been receptive to warnings given by his guardians in the spirit world. On the other hand, we do not know the full picture in terms of his karma or lessons in this lifetime. Madero performed great works when he was physically present. I am sure that these great works would have continued in other realms after his physical death.

C.M. MAYO: In the introduction to your book, Mediumship Mastery, you mention that you trained as a hypnotherapist. From his personal library we know that Madero was intensely interested in hypnotism. Would this knowledge have enhanced his abilities as a medium and as a political leader? And if so, how?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: Kardec and many of the pioneers of the Spiritualist movement studied Mesmerism and altered-states-of-consciousness. The awareness of inducing trance states is crucial for the development of mediumistic ability. For example, with clairvoyance the more the medium is able to place his or her mind into a receptive state and get the analytical mind out of the way, the easier it will be to receive as well as accurately interpret spirit messages given in this manner. Mediumship mastery requires considerable discipline on the part of the medium. Hypnosis is an effective tool for helping student mediums train their minds and open up as instruments for the spirit personalities to work through.

ON SPIRITISM, SPIRITUALISM,

THE PHILIPPINES, AND PSYCHIC SURGERY

C.M. MAYO: Spiritism developed in France from the root of Anglo-American Spiritualism. As a medium who has practiced and taught in various countries from the U.S. to New Zealand and including in the Philippines, do you see important differences in these traditions, Spiritualism and Spiritism, today?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: Spiritism and Spiritualism are branches of the same tree. A Spiritist is a Spiritualist who follows primarily the doctrine found within Kardec’s writings. Anglo-American Spiritualists do not limit themselves to Kardec’s writings and as a whole have not officially embraced the concept of reincarnation. The Spiritist approach generally places more emphasis on higher philosophy and less on phenomena or providing evidence of survival as the Spiritualist approach emphasizes. I think as a whole the Spiritist approach tends to be more progressive than what is found in many Spiritualist churches. However, Spiritists can be a bit dogmatic in adhering to Kardec’s writings.

C.M. MAYO: In your chapter “Spiritiual Healing” you discuss psychic surgery in the Philippines. Though Madero does not discuss psychic surgery in the Spiritist Manual, in my book, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution, I mention the Filipino and Brazilian psychic surgeons as well as some Mexicans including Niño Fidencio and Doña Pachita because they are well-known in Mexico and I felt they represented traditions that could claim at least some tangly bit of roots in the early 20th century Spiritism of Madero. Would you agree? Also, have you practiced and/or witnessed any psychic surgery yourself?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: There have always been mediums or healers in all cultures. The Philippines were a Spanish colony for almost three hundred years. Many of the leaders of the revolution against Spanish rule were involved in the practice of Spiritualism. Kardec’s writings were again a major influence in this part of the world.

I teach mediumship and healing worldwide and the Philippines is one of the countries I regularly visit. Over the years I have witnessed and experienced many remarkable physical and emotional healings with my own mediumship as well as the mediumship of others. With healing God is the healer and we are only vehicles for God’s unconditional love to work through. Yes, I practice psychic surgery with the help of spirit doctors. However, I do not pull blood and guts out of people and drop it in a tin can as many Filipino healers do.

C.M. MAYO: My understanding is that Spiritism arrived in the Philippines with Spanish translations of Kardec’s works. Presumably many of these came out Barcelona, an important center for esoteric publishing (and indeed, many of the books in Madero’s personal library were from Barcelona). When I discovered that Madero’s 1911 Manual espírita had been reprinted by Casa Editorial Maucci in Barcelona in 1924, I immediately wondered whether any copies had made their way to the Philippines and so played some role in the spread of Spiritism there. Do you know anything about this?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: I do not know anything about this. Don Juan Alvear in 1901 founded the first Spiritist center in San Fabrian, Pangasinan. I have worked at this center many times and the energy is amazing. Alvear was a great political leader, educator and prominent intellectual. Like Madero, Alvear authored a book on mediumship and was a hero of the revolution. His statue is outside the government building and across the street from the Spiritist center he founded.

[C.M. MAYO: See Hermann’s blog post about some history of Spiritism in the Philippines here. And for more about Spiritism in the Philippines, a subject on which I am admittedly very foggy, one place to start is Harvey Martin’s The Secret Teachings of the Espiritistas.]

ON THE BHAGAVAD-GITA AND REINCARNATION

C.M. MAYO: In many places in your book, Mediumship Mastery, you quote from the Bhagavad-Gita.This was a work that fascinated Madero; he not only mentions it in his Spiritist Manual, but under the pseudonym “Arjuna”— the name of the warrior in the Bhagavad-Gita— he wrote articles about it and was planning a book about its wisdom for the modern world. The Bhagavad-Gita also had an important influence on Gandhi, Emerson, the Theosophists, and many others. One of its many teachings is about reincarnation. In your book’s chapter “Past Life Readings,” you mention that you have recollections of some of your past lives and also have received communications from spirits about others’ past lives. Would you elaborate on reincarnation as explained in the Gita?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: The Bhagavad Gita is a conversation between the Supreme Personality and Arjuna. I try to read it as much as possible. Life is eternal as the personality continues into the world of spirit. The Bhagavad Gita explains the science of connecting with the Godhead and how to cultivate devotion or love of God. Every seven years pretty much all the molecules in our physical bodies change. So we are always changing physical bodies. Based on our consciousness at the end of this physical life we will end up having to take another physical birth. The Gita explains the process of transmigration and how we can ascend to higher levels.

C.M. MAYO: Like Madero in his Spiritist Manual, in your book, Mediumship Mastery, you advocate a vegetarian diet. Is this an idea that came to Spiritualism / Spiritism from Hindu philosophy?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: Higher teachers on both the physical and spiritual worlds always advocate vegetarianism as it is very bad to hurt animals and cause suffering to others. A true follower of Jesus would not want to hurt others as would a true follower of Buddha. There is only one God and we are all God’s children. I am sure Madero was influenced by Vedic teachings which is why he loved the Bhagavad Gita.

MORE ABOUT MADERO’S SPIRITIST MANUAL

C.M. MAYO: What surprised you the most about Madero’s Spiritist Manual?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: I really loved reading the Spiritist Manual. It didn’t really surprise me as I am familiar with everything he wrote already. However, I especially loved reading the extra sections about your research and his notes, etc. I think you did a fantastic job.

C.M. MAYO: In terms of his understanding of mediumnistic unfoldment—or anything else—are there any points where you would disagree with Madero’s Spiritist Manual?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: Madero approaches mediumship heavily influenced by Kardec’s Medium’s Book. Nothing wrong with that as Kardec’s work was way ahead of it’s time when it was published in 1861. However, the methods and approaches used by the spirit personalities to communicate, train and interact with mediums have greatly improved.

Back in the early years of Spiritualism there were no teachers of mediumship. Mediums learned through trial and error and with the assistance and input of teachers in the spirit world overtime created structured approaches to the unfoldment of the various phases of mediumship.

Madero was brilliant and had he not have been murdered his mediumship would have expanded even more. Love, harmony, enthusiasm, and higher purpose are the qualities needed to create the best conditions for successful mediumistic communications. Madero possessed all these qualities and more.

In the early years of Spiritualism there was much physical phenomena or manifestations of spirit power that could be directly experienced through the five physical senses. Nowadays, people are much more intellectually oriented and as such the mediumship practiced is mainly mental or telepathic in nature. It is not that one method is better but just better suited for the age. The methods for training mediums have greatly improved and expanded in the last 168 years.

C.M. MAYO: As you were reading Madero’s Spiritist Manual, or before or afterwards, did you ever sense that you were in communication with / sensing Madero’s spirit? Is there anything you would like to say about that?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: I would think that Madero most likely would have been around you a lot when you were researching and writing the book. I do not know if he was around me when I was reading the book, but I do feel that he and I would have a lot in common if we were to meet. I think we would get along pretty well as I can relate to where he was at in terms of his mediumship and his spirituality in general.

C.M. MAYO: In your book, Mediumship Mastery (p. 9) you introduce the subtle bodies that interpenetrate the physical body. As I read it, this is a somewhat different explanation from given by Madero where he, following Kardec, talks about the “perispirit.” Can you explain?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: The perispirit is the subtle or astral covering. Madero uses Kardec’s terminology. We have a physical body with subtle bodies interpenetrating it. After physical death the soul continues to function through the astral body and travels into the spirit world.

ON MEDIUMSHIP AND ENERGIES

C.M. MAYO: My experience has been that not all but most people either dismiss mediumship as impossible or, believing it possible, are frightened that, in calling on the spirit world, they might encounter negative entities. In particular, the Catholic and many other churches sternly warn against dabbling in conjuring spirits, especially with Ouija boards. In the introduction to your book, Mediumship Mastery, you write, “In all my years of working as a medium, I have never experienced anything negative or that made me feel uncomfortable. My experience of mediumship has always been genuinely positive, loving, and comfortable.” It would seem, from my reading of the Spiritist Manual, that Madero would have agreed. But has this been the case for others you know?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: Mediumship is all about love and healing. However, training is important as is proper motivation. Someone could have a bad experience with mediumship if they dabble in it or go about doing it in a superficial way. Spiritual mediumship is completely orchestrated by higher spirit personalities. Mediumship is not a board game for drunk teenagers to play at 2 AM. Like attracts like.

C.M. MAYO: In your book’s final chapter, “Dealing with Skeptics,” you write, “People who are closed off and negative for any reason, which would include hardcore skeptics, are exceptionally more difficult to work with as the energies are not as strong, the links to the spirit world weaker, and the connections more incomplete and vague.”

It seems to me that U.S. Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, who disdained Madero as mentally unbalanced and who, for his support for the coup d’etat that ended with Madero’s murder in 1913, has gone down as one of the archvillians of Mexican history, had much in common with the rigidmindedness of celebrity skeptics such as the Amazing Randi. Would you agree?

STEPHEN A. HERMANN: I don’t know Randi personally nor do I know the US Ambassador of that period. Who knows what motivates people on a deeper level? However, Randi does seem very closed off to higher consciousness and intuitive ability. I suspect that Ambassador Wilson was motivated completely by lower, selfish interests and as a result would have cut himself off from higher spiritual influences.

Skeptics are not necessarily immoral or callous individuals. They just do not often believe in the mystical and are highly suspect of claims that do not fit their rationalist view of the world. I appreciate skepticism as many people are completely gullible and easily misled. It is important to not throw out your intelligence when dealing with mediumship as there is a fine line with genuine psychic impressions and your own imagination.

#

> Visit the webpage of Rev. Stephen A. Hermann, author of Mediumship Mastery

> Visit the web page for Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and His Secret Book

> Visit the webpage for my book, together with a transcription of Madero’s Manual espírita, in Spanish, Odisea metafísica hacia la Revolución Mexicana.

> Visit the webpage for Resources for Researchers

What Is Writing (Really)?

Plus A New Video of Yours Truly Talking About

Four Exceedingly Rare Books Essential

for Scholars of the Mexican Revolution

Why Translate? The Case of the President of Mexico’s Secret Book

The Book As Thoughtform, the Book As Object:

A Book Rescued, a Book Attacked, and

Katherine Dunn’s Beautiful Book White Dog Arrives

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.