This blog posts on Mondays. This year the fourth Monday of the month is, except when not, dedicated to a Q & A with another writer.

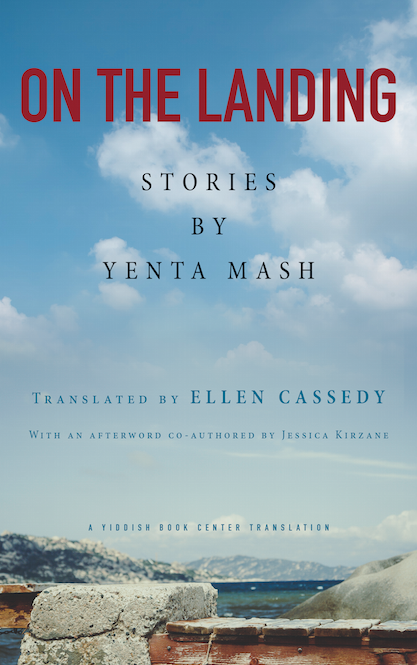

Yenta Mash and her stories will be remembered because they have rare and masterful elegance, uncanny insight into vast prairie-like swaths human nature, and unusual heart. They also tell stories entirely new for many English-speaking people, that of the Jewish exiles to Siberia under Stalin during World War II, and their later migration to Israel. Translator Ellen Cassedy’s is a transcendent achievement; with Mash’s On the Landing she has brought a landmark book into English.

Translator Ellen Cassedy’s is a transcendent achievement; with Mash’s On the Landing she has brought a landmark book into English.

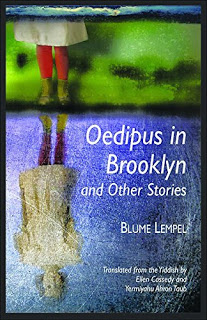

Ellen Cassedy is the author of We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust and co-translator (with Yermiyahu Ahron Taub) of Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories by Blume Lempel. She was a 2015 Yiddish Book Center Translation Fellow, and On the Landing is a result of her fellowship. Her website is www.ellencassedy.com.

C.M. MAYO: How might you describe the ideal reader for these stories?

ELLEN CASSEDY: Anyone interested in fine literature! Mash is a great read – clear, sometimes funny, and full of ground-level truths about what it was like to live through great cataclysms of the 20th Century.

C.M. MAYO: When and why were you inspired to translate Yenta Mash?

ELLEN CASSEDY: I learned of Mash’s work through the Yiddish Book Center’s translation fellowship program. Having died in 2013, she’s basically a contemporary writer. She was a down-to-earth and often witty observer of a changing world, who drew on her own life of multiple uprootings in telling the stories of people who are forever on the move.

Even in the most harrowing settings, Mash is somehow inspiring. Young and old, her characters are solid, sturdy people with a sense of humor. They’re survivors, people who land on their feet.

The collection begins in a vibrant Jewish town reminiscent of the one in “Fiddler on the Roof.”

We then join women prisoners being transported into the Siberian gulag, with its frozen steppes, snowy forests, and surging rivers. After the exile, we see the Jewish community rebuilding itself behind the postwar Iron Curtain. Finally, we join refugees in Israel in the 1970’s, struggling with the challenges of assimilation and the awkwardness of a land where young people instruct their elders, instead of the other way around.

C.M. MAYO: You are also a translator of the Yiddish writer Blume Lempel. Both Lempel and Mash write of suffering, exile, and grief, and yet they are very different writers, with very different experiences during and after the war. In a writerly sense, what are some of the differences that especially strike you?

ELLEN CASSEDY: Mash (1922-2013) and Blume Lempel (1907-1999) grew up in tiny towns in Eastern Europe, not far apart from each other. Both suffered persecution, displacement, and appalling losses.

Lempel left home for Paris as a young woman, fled to America in 1939, and spent the remainder of her life in New York. Her work feels shattered, fractured, unhinged. Her gemlike, poetic style and decidedly unconventional narrative strategies take readers into a realm of trauma and madness. The title story, “Oedipus in Brooklyn,” is Exhibit #1 of her taboo-defying oeuvre.

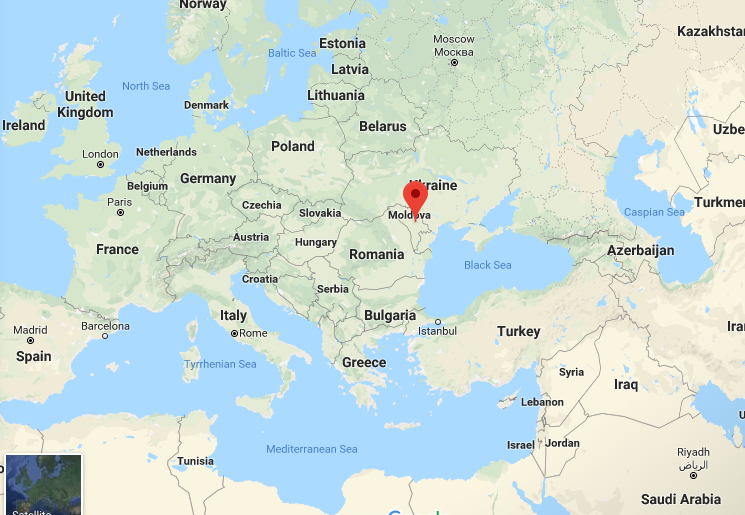

As a young woman, Mash was deported to Siberia by the Soviets in 1941. She did seven years of hard labor there, then spent three decades in Soviet Moldova before immigrating to Israel in the 1970’s. Her work bears witness in an urgent, orderly, and exacting fashion to a life full of tumult. Her language is alive with regionalisms carried to new places, bits of multiple languages picked up along the way, and neologisms invented to describe new circumstances.

C.M. MAYO: In our last interview, about your translation (with Yermiyahu Ahron Taub) of Lempel’s stories, Oedipus in Brooklyn, I was intrigued, if not surprised, to learn that she corresponded with the poet Menke Katz. Would Blume Lempel and Yenta Mash have corresponded, or have corresponded with anyone in common in Yiddish and other literary circles?

ELLEN CASSEDY: The world of Yiddish writers after World War II was like a virtual café on a global scale. Yiddish newspapers, literary journals, and literary prizes flourished, as did intense epistolary friendships. I don’t have any evidence that Mash and Lempel corresponded, but they must have read each other’s work in Di goldene keyt, the flagship literary journal published in Tel Aviv. And they knew some of the same Yiddish literary figures, including the eminent poet and journal editor Abraham Sutzkever.

“The world of Yiddish writers after World War II was like a virtual café on a global scale. “

C.M. MAYO: How did working on On the Landing compare to working on Lempel’s Oedipus in Brooklyn and to your other translation projects?

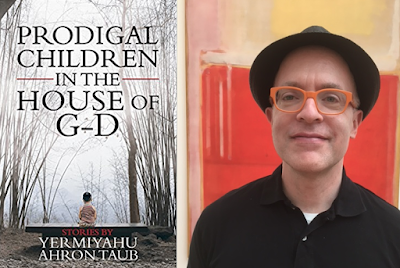

ELLEN CASSEDY: I was fortunate to have Yermiyahu Ahron Taub as a co-translator for the Lempel project. We had a rich collaboration, full of constant back and forth. For the Mash project, I drew on the resources of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, MA – a wonderful organization that provided me with mentors and a vibrant and an engaged community.

I did the English translation for Yiddish Zoo, a collection of Yiddish poetry for children in three languages. That was a joyful romp with lions and tigers and bears – great fun.

Now I’m working with a gifted cartoonist who’s embarked on a graphic project involving handwritten Yiddish archives. Quite a decoding challenge!

C.M. MAYO: Can you talk about Yenta Mash’s literary influences? (And in which languages did she read?)

ELLEN CASSEDY: Mash knew Russian, Rumanian, Hebrew, and Yiddish. She was drawn to Yiddish literature from early childhood. As a small child, she knew poems by Y.L. Peretz by heart and was familiar with the classical Yiddish writers Sholem Aleichem and Mendele Moykher Sforim. After her years in Siberia, she joined the vibrant Jewish literary circle in the Moldovan capital of Chisinau. But it wasn’t until she was in her fifties, when she immigrated to Israel, that she began to write. She joined the Yiddish literary scene in Israel and was a member of Leivick House, a Yiddish cultural center.

C.M. MAYO: Which writers, in any language, could you compare her to?

ELLEN CASSEDY: Yenta Mash is a master chronicler of exile. Her characters are always on their way to somewhere or from somewhere. That’s why I chose the name “On the Landing,” the name of one of her stories, for the title of my translated collection.

“Yenta Mash is a master chronicler of exile.”

I compare her to other voices of assimilation and resilience – Jhumpa Lahiri (The Namesake), André Aciman (Out of Egypt), and Viet Thanh Nguyen (The Refugees). Her work is keenly relevant today as displaced people seek refuge across the globe.

C.M. MAYO: I am astonished that writing of such quality is only appearing in English for the first time in 2018. Is there more?

ELLEN CASSEDY: Absolutely! Only a fraction of Yiddish literature from the past 150 years has ever been translated into English. As we gain access to more and more of these buried treasures, I believe Yiddish literature will take its rightful place in the world, as what has been called “a major literature in a minor language.”

“As we gain access to more and more of these buried treasures, I believe Yiddish literature will take its rightful place in the world, as what has been called ‘a major literature in a minor language.'”

There’s an expression in Yiddish, “di goldene keyt,” the golden chain, which refers to how Yiddish literature has been passed down through the ages, with one writer after another adding links to the chain. Yiddish was the language that my Jewish forebears spoke in kitchens, marketplaces, and meeting halls on both sides of the Atlantic. I’m thrilled to be able to add my own link to the chain.

Q & A with Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub on Translating Blume Lempel’s Oedipus in Brooklyn from the Yiddish

Q & A with David A. Taylor, Author of Cork Wars: Intrigue and Industry in World War II

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.