This blog posts on Mondays. Fourth Mondays of the month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

Reading poetry in translation can be like wafting through a door into an eerily beautiful palace. The tiles glow in new colors, shapes are peaked or oval when you expect square, juxtapositions startle, and the cats don’t meow but miau or nya or, as in Norwegian, mjau…

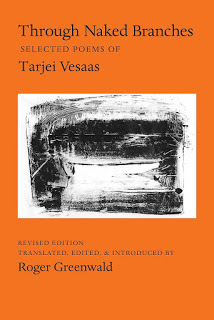

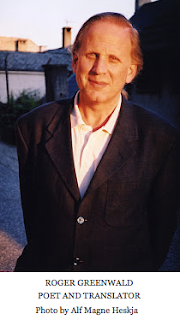

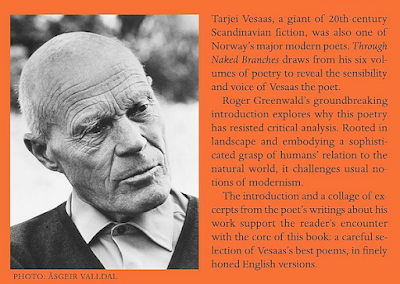

Apropos of the just-published translation from the Norwegian, Through Naked Branches: Selected Poems of Tarjei Vesaas, it is a delight and an honor to post this interview with one of the most accomplished poets and translators working in English today: Roger Greenwald.

C.M. MAYO: How might you describe, in just a sentence or two, the ideal reader for this book?

ROGER GREENWALD: These poems are accessible but deep, and they reflect an unusual sensibility, so anyone who is open to a new experience in poetry is an ideal reader. My introduction explores why this poetry that is easy to “get” is so hard to discuss critically; the essay will be of special interest to people concerned with our relation to the natural world and with ecocriticism.

CMM: What inspired you to translate this work?

RG: Tarjei Vesaas was and is a famous novelist, but his poetry was like a secret shared among other writers and a small number of readers. When I first read his poems, I realized that the best of them were unlike any I had ever read. In addition to his special sensibility, he has a distinctive voice, pace, and turn of phrase, as well as a very fine ear for the music of language. And by the time of his death in 1970, almost none of his poetry was available in English, never mind in versions that did it justice. In some ways it is very difficult to translate. Twenty years passed before I had translated a selection to my satisfaction, and then it took me another eight years (eight drafts) to write my introduction.

CMM: How did you learn the language?

RG: This apparently simple question poses a problem at once: Which language is “the language”?! I first learned Norwegian on my own from a textbook. But Norwegian has two official written norms, and the textbook was about Bokmål, which ultimately derives from Danish and reflects Norway’s urban dialects. Tarjei Vesaas wrote in Nynorsk, which ultimately derives from Old Norse via Norway’s rural dialects. I advanced my knowledge of Bokmål by living in Norway at various times, by doing more reading, and by bothering my friends with a million questions. Dealing with Nynorsk required further study, and I cannot claim to have mastered it even as a reader, so I need more advice and feedback when translating from it than when translating from Bokmål.

CMM: What was the most important challenge for you in this translation?

RG: Vesaas has certain characteristically odd turns of phrase that are difficult or impossible to render in English. They stretch Norwegian but are not un-Norwegian, so they require creative equivalents that stretch English but are not un-English. And of course English cannot be stretched in exactly the same was as Norwegian can be. But the greatest challenge lay in the responsibility I felt to introduce English-speaking readers to this poetry in a way that would help them to see that it was modern even though it was not urban, and that its relation to the natural world was profound and not a throwback to the English Romantic poets.

CMM: Has his work been an influence for your work as a poet?

RG: I think Vesaas’s poetry hasn’t exerted as great an influence on my own poetry as has the work of some other Scandinavian poets, but in one of my poems (“The Milky Way. Big and Beautiful”) I refer to him and quote three lines; and I’d say that in another (“The Voice”), the deliberate pace and the way silence creeps into the stanza breaks probably owe something to Vesaas.

CMM: You have been a consistently productive poet and writer for many years. How has the digital revolution affected your writing? Specifically, has it become more challenging to stay focused with the siren calls of email, texting, blogs, online newspapers and magazines, social media, and such? If so, do you have some tips and tricks you might be able to share?

RG: I started using computers in the early 1970s to produce files for the literary annual I edited, WRIT Magazine. Coach House Press, where the journal was printed, was a test bed for cutting-edge digital typesetting and layout. I learned enough about computerized editing and typesetting on a UNIX system so that I could take advantage of it for my own work for about twenty years before I acquired my first Windows machine. This was an enormous benefit when it came to revision, especially for translations, and it enabled me to get book manuscripts several stages closer to publication than had been possible earlier. I felt that computers trebled my productivity, not in the sense that I wrote more or translated more, but insofar as they saved large amounts of time and encouraged me to produce finished manuscripts and files that I knew could be used for printing.

That was, you might say, the first digital revolution, the second being that of the Internet and later the World Wide Web. Online resources have made it much easier and faster to answer certain questions that arise in writing and translating, whether these be about language as such, about allusions in texts, or about what a certain landscape, building, or object looks like. Email has greatly facilitated getting advice and feedback from friends and colleagues in distant locations, consulting with authors I’ve translated, and getting proofs from publishers. And the web has made it possible for me to post descriptions of my books, sample poems, and ordering links.

Resisting distraction is really a question of psychology, work habits, and time management. We tend to forget that it was almost as easy to be distracted and to waste time before the Internet existed as it is now. One could read magazines and watch TV for hours a day. Those were, though, less fragmented activities than online distractions can be now, and were less likely to interrupt constantly. I made an early decision to stay off all social media, mainly because of concerns about privacy and distrust of the motives and methods of people like Mr. Green T-shirt. That decision has meant being uninformed about a few events now and then, and it has perhaps reduced my ability to promote my work (how many people would really have followed a Facebook page that posted new material only a few times a year?). But it has prevented most of the woes we all associate with social media, including invasion of privacy, online harassment, and the expense of countless hours on reading and posting.

CMM: Another question apropos of the Digital Revolution. At what point, if any, were you working on paper? Was working on paper necessary for you, or problematic?

RG: In my formative years, my choice was between handwriting on paper and writing on an electric typewriter. I always used paper then for any work that required real thought and much revision during the writing process. Later I got to the point where I could write letters and reports on the typewriter, and sometimes even fiction when it was driven by a type of nervous energy that was in tune with the hum of the typewriter. Even after decades of using computers, I still write poetry by hand, and I tend to translate poetry by hand also. I can write a first draft of fiction or translated fiction on a computer. Handwritten drafts make it easier to see all the choices one has tried and then crossed out.

CMM: What’s next for you as a poet and as a translator?

RG: I have more or less withdrawn from translation to focus on my own work (there is one more large translation project that I may or may not get to someday). But I do what I can for my previously published translations, like the Tarjei Vesaas book, which was first published in 2000 and was out of print for many years. Finding a publisher for a new edition enabled me to make revisions – the second time I have been able to revise and/or expand a major selection (on the other occasion the gap was from 1985 to 2002, when the University of Chicago Press issued North in the World: Selected Poems of Rolf Jacobsen). Don’t ask me whether such opportunities are translators’ dreams or nightmares!

My first book of poems was published in 1993, my second (Slow Mountain Train) in 2015. Now I am hoping to get out my third and fourth books in the next two years. I have manuscripts beyond those and will be working on getting them into near-final form. So get off Facebook and watch my website: www.rogergreenwald.org !

P.S. Click here to read Greenwald’s Q & A for Madam Mayo blog about his translation of Swedish poet Gunnar Harding’s Guarding the Air, from July 2015. See also Greenwald’s lecture for the University of Chicago in its series History and Forms of Lyric.

Q & A: Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub on Translating Blume Lempel’s Oedipus in Brooklyn from the Yiddish

Blast Past Easy: A Permutation Exercise with Clichés

Catamaran Literary Reader and My Translation of

Mexican Writer Rose Mary Salum’s “The Aunt”

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.