Madam Mayo blog’s “madmimi” email sign-up is finally working, over there on the sidebar. Subscribe and each Monday you will receive the latest post (and nothing else– no spam). Mexico, poetry, rare books, Texas, translation, the typosphere, occasional pug-sightings– if these tickle your fancy this is the blog for you! Second Mondays are for my workshop students and anyone else interested in creating writing; fourth Mondays are for a Q & A with another writer.

It’s too long a story what happened to the Q & A for this month; however I offer you this fascinating Q & A from the Madam Mayo blog archives.

Q & A WITH ROGER GREENWALD, POET

AND LITERARY TRANSLATOR OF GUNNAR HARDING

(Originally posted July 1, 2015 on Madam Mayo blog’s original blogger platform. Madam Mayo blog has since migrated to this new self-hosted WordPress site.)

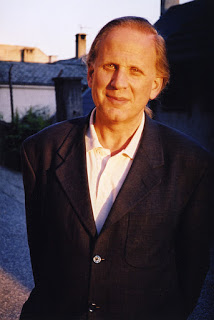

Photo by Alf Magne Heskja

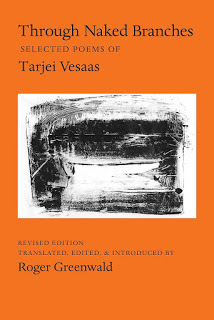

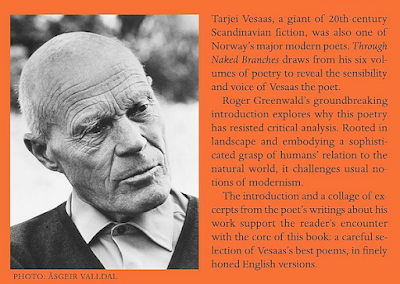

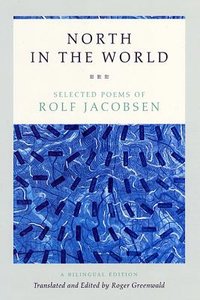

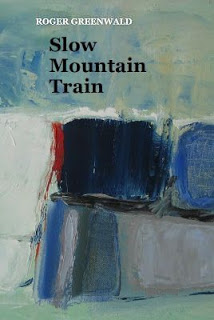

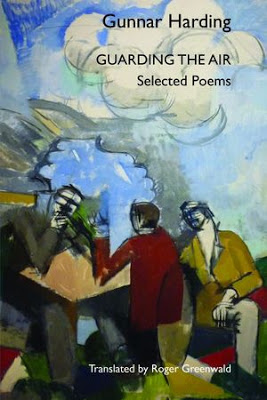

I got poet Roger Greenwald on my radar when we crossed paths at last year’s American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) conference in Milwaukee [see my post Why Translate?], and I began to read his gorgeous latest translation, Guarding the Air: Selected Poems of Gunnar Harding. (Greenwald’s latest book, actually, is Slow Mountain Train, more about that after the Q & A. Important point: I have always believed, for it has always been my experience, that the best literary translators are poets.)

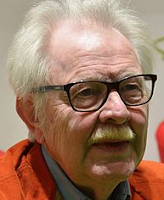

Gunnar Harding, a jazz musician, painter, essayist and a translator himself, is one of Sweden’s leading poets. Surely Harding is one of Sweden’s most prolific as well; Greenwald has selected numerous poems from more than a dozen of his books. Strange, witty and jazzy, Harding’s poems wing from the moon’s Sea of Tranquility to nickels in a jukebox (“Rebel without a Cause”).

> Visit Greenwald’s webpage for the book, which includes some of the poems and a video of the launch, here.

> Read the review by Christine Roe for Words Without Borders. “Spanning a lifetime of poetry, Guarding the Air pays homage to tragically under-translated Swedish literary legend”

> Gunnar Harding on Swedish Wikipedia

(Note: I’m not a fan of Wikipedia, but alas I could not find much else on Gunnar Harding. Caveat emptor.)

ROGER GREENWALD attended The City College of New York and the Poetry Project workshop at St. Mark’s Church In-the-Bowery, then completed graduate degrees at the University of Toronto. His poetry has appeared in such journals as The World, Pequod, Pleiades, Poetry East, Prism International, The Spirit That Moves Us, The Texas Observer, Great River Review, and Leviathan Quarterly. He has won two Canadian Broadcasting Corp. Literary Awards (poetry and travel literature) and has published two books of poems: Connecting Flight from Williams-Wallace in Toronto and in April 2015, Slow Mountain Train, from Tiger Bark Press in Rochester, New York.

C.M. MAYO: In a sentence, why should readers pick up this book?

ROGER GREENWALD: This selection spans the whole career of a major poet whose work is accessible and appealing– and also strong in both idea and feeling.

C.M. MAYO: What were the challenges for you as a translator?

ROGER GREENWALD: First I had to understand each poem in depth, of course, and in this case that meant understanding not only the language and the “argument,” but a broad range of allusions to other literary works, paintings, recorded music, places, people, and so on. (I’ve put pointers to these in endnotes.)

The biggest challenge, as always, was to write in English poems that had something like the voice and the music of the source. People assume that it is easier to translate poems written in a colloquial voice than to translate work full of neologisms, broken syntax, word play, and other notoriously “tough” features. But the fact is that those features give a translator license to be creative and sometimes to sound “strange”; whereas to translate a whole book in a colloquial voice, getting the literal sense and the line units and the music right while never once sounding odd or “translated” is just as hard or harder.

C.M. MAYO: What advice would you offer others who might consider undertaking a poetry translation?

ROGER GREENWALD: Translate into your native language. If you’re not doing that, you need to collaborate with a poet whose native language is the target language. Try to live for at least a year in the country that your poet and his or her language come from. Read not just the major works from that country’s literature, but some of what children read in school years, like fairy tales. Get to know some of the art and music. Watch TV and listen to radio. And ask a lot of questions, especially about the language, its idioms, its peculiarities. When you start understanding friends’ jokes, stand-up comics, and locally made comedy films, you will know your cultural immersion has worked.

C.M. MAYO: As a member of the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA), can you talk about what the benefits have been for you as a translator?

ROGER GREENWALD: The greatest benefits have come from sharing knowledge and experiences with other translators. Seeing and hearing their work and discussing how they approached certain texts gave me useful insights into practice. But it was also important to learn about how to navigate relationships with authors and their publishers, how to find suitable potential English-language publishers, how to present work to those, and how to avoid getting burned by unfair contracts. Simply hearing, in the Bilingual Reading series at ALTA conferences, a great range of usually unpublished work, some of it still in progress, has been an ongoing source of delight and inspiration.

And beyond that, it’s worth saying that literary translators have to be some of the most interesting people in the world, with extremely diverse backgrounds, experiences of foreign cultures, and knowledge of wonderful writers who are little known in English, even if their work has been translated and published. So it has been great to get to know my fascinating colleagues!

C.M. MAYO: Are there are other associations you would recommend?

ROGER GREENWALD: None that I belong to. But I have had it in mind for some time to look into the Authors Guild, because it is focused on advocating for fair treatment of authors and translators. And this seems to be an issue of growing concern as digital media undermine publishing revenue, and as companies like Amazon demand deep discounts and exert downward pressure on the sale price of both paper and electronic books.

[C.M.: See my post Shout-out for the Authors Guild.]

C.M. MAYO: Where can readers find a copy of this book?

ROGER GREENWALD: I’m happy to say that the publisher of Guarding the Air has excellent worldwide distribution. So readers can buy it directly from the press at www.blackwidowpress.com (choose “Modern Poets” or use Search); they can order it through any independent bookseller they care to support; or they can buy it on line from Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

It’s also worth remembering that readers can ask their public library or their college library to acquire the book.

+ + + + + + + + + +

+ + + + + + + + + +

From Roger Greenwald’s new book of poems, Slow Mountain Train:

Next post next Monday.

Using Imagery (the “Metaphor Stuff”)

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.