BY C.M. MAYO — July 25, 2022

UPDATE: This blog was then entitled Madam Mayo (2006-2022).

This blog posts on Mondays. The fourth Monday of every other month I devote to a Q & A with a fellow writer.

“Think fencing salle meets monastic scriptorium meets electric choir.” — Rachel Fulton Brown

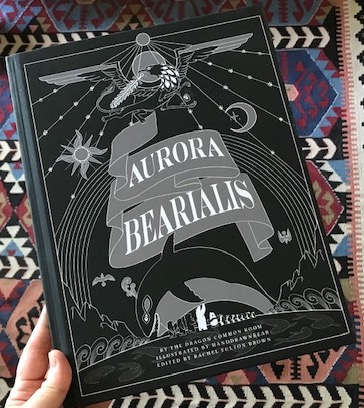

A product of the on-the-edges cultural renaissance burbling up out of covid times, Aurora Bearialis is one of the most beautiful, original and charming books I have ever encountered. It is, by the way, a Christian children’s book modeled on medieval romance, brought into the world by a group of poets who meet online (group chat on Telegram), and by historian Rachel Fulton Brown. Visit her University of Chicago academic homepage; her “not-so-academic” blog; and her Dragon Common Room Books.

by The Dragon Common Room,

Illustrated by Handdrawnbear,

edited by Rachel Fulton Brown

C.M. MAYO: What is the Dragon Common Room, and what inspired you to write Aurora Bearialis?

RACHEL FULTON BROWN: The Dragon Common Room (DCR) is an online “digital classroom” which I started in May 2020 as a place for training in the art of Christian minstrelsy. Think fencing salle meets monastic scriptorium meets electric choir. In practical terms, DCR is a group chat on the social media platform Telegram, its members drawn from around the internet by their interest in Christianity, poetry, and imaginative mischief making. The core group of poets have been working together now for over two years, honing our ability to write in iambic pentameter.

Aurora Bearialis is our second book. Our first book, Centrism Games, is a biting satire on the modern lack of virtue in the pursuit of Fame. Having delved into the hypocrisies and horrors of our adult world in this first poem, we wanted to write something more hopeful for children, modeled on the grail quests and chivalric adventures of medieval romance. We wanted to give children something challenging but fun that would invite them into the world of Christian symbolism. We chose animals as our main characters to give the story a more “fairy tale” quality, but with grounding in our primary reality.

Perhaps the best description of Aurora Bearialisis “Dante for children”: a medieval-style comedy working on multiple levels—historical, allegorical, moral, and mystical—with bears, penguins, and an albatross, who go in search of the Light.

C.M. MAYO: How did you find Handrawnbear? Because, Wow!

RACHEL FULTON BROWN: Handdrawnbear found us! She had been working for several years making drawings and animations at unBearables Media (https://unbearablesmedia.com/hand-drawn-bear/). I was in touch with one of their other creators and asked if there were anyone interested in doing illustrations for our new bear poem. Being a “bear,” she jumped at the chance! She has written on her own blog about how working with us has inspired her to write more Christian poetry (https://handdrawnbear.com/blogs/handdrawn-journal/the-once-mute-bear-finds-her-voice).

I notice that in her version of the story, I found her. This is a taste of what it was like working on Aurora Bearialis: it often felt as if the poem were writing itself or that we were discovering it along with the penguins and bears. To this day, I have only a vague memory of who wrote what or even whether the words or pictures came first. More often than not, we would be writing, and Handdrawnbear would show us her sketches, and we would suddenly realize what came next thanks to her drawings. And yet, she remembers the process as finding the visuals to fit the words. Both are true!

C.M. MAYO: As you were writing and editing and assembling Aurora Bearialis, did you have in mind an ideal reader? If so, might you say more about that ideal reader?

RACHEL FULTON BROWN: Our ideal reader is a child aged 8-12, with younger and older siblings or friends. We had long discussions over the vocabulary for our poem. We wanted it to be challenging enough to send readers (or listeners) to the dictionary, but whimsical enough to make them laugh. The poem alternates high mysticism with physical comedy, so, for example, after Abner the albatross tells our hero, the polar bear Ulfilas, about the melting stars in the Southern sky, he has to taunt the bear to get off his butt and swim for it, whereupon the polar bear bites the albatross in the butt, claiming a feather.

We were also concerned to write a story for children with a strong moral, as well as a story that would point them to the beauties of the Christian liturgy. The characters in the story needed to grow in understanding over the course of their adventure and to face real threats to their courage. At the same time, we wanted the reader to feel caught up in the story, striving with the bears to answer the riddles that the penguins set. Conversely, we wanted the pictures to set puzzles that the text could not express, much as medieval manuscripts—or comic books—rely on both image and word. Thanks to Handdrawnbear’s experience with animation, it is possible to “read” the story simply by looking at the pictures, while the text points the reader to “Easter eggs” in the pictures only whales (or children dancing before the Ark) can find.

C.M. MAYO: What was the most challenging aspect of publishing this book?

RACHEL FULTON BROWN: Technically, the hardest part of publishing this book was the graphic design, for which we got help from one of Handdrawnbear’s friends, but the biggest challenge overall has been learning to work as a team. Telegram as a platform works amazingly well as a place for dynamic conversation. There, we are able not only to write, but also to share images, voice messages, and links, making it easy to compile references for both drawings and text. The difficulty comes as it does in any creative work with keeping to task while allowing inspiration to strike.

My solution: work and pray like medieval monks! The “drakes” meet as a group every weekday at 6pm CST, starting and (ideally) stopping after exactly an hour. My experience as a writer and teacher has obviously been helpful, but the drakes have given me energy and companionship that I have never experienced as an academic historian working primarily on single-author articles and monographs. It has been a challenge for me articulating my own creative process to a group—setting goals, writing outlines, keeping to the daily practice—but it has also been a joy being able to suggest an idea to the group and watch it blossom and fruit in ways I could never have envisioned on my own.

C.M. MAYO: What has most surprised you about its reception? (And what has been its reception among your academic colleagues?)

RACHEL FULTON BROWN: It has surprised me most being swarmed by the children at St. John Cantius Church when I did a reading for them one Sunday after Mass! (I think they liked it, especially the part where the Griffin grabs the Panda as he is eating the offerings on the altar.) I have also done presentations on the book for a conference on Christian literature, which we recorded as a lecture at Cantius for the parents (https://youtu.be/5AmMrBXFgUM), and I have presented on it to the Catholic Society at Hillsdale College.

When I talk about the book with my academic colleagues, they are, of course, dazzled by the pictures, but I can see them getting thoughtful about what it means to recover medieval Christian storytelling in a digital mode.

In the Dragon Common Room, we are using a digital medium (Telegram) to write metered poetry that reads like medieval exegesis of Scripture, on multiple levels simulatenously, with pictures and words working together to recover a multisensory awareness of metaphysical truth. Is academia with its visual focus on print ready for acoustically resonant Dantean poetry? The children at Cantius are!

C.M. MAYO: Which writers have been the most important influences for you as a creative writer, and also, specifically, when you were writing Aurora Bearialis?

RACHEL FULTON BROWN: I have been teaching a course at the University of Chicago on J.R.R. Tolkien for almost twenty years now, the final project for which is an invitation to “sub-create” within Tolkien’s legendarium in an artistic medium of the students’ choice. There is definitely something of Tolkien’s hobbits in our band of bears setting off on a quest that brings them to a mountain of fire, but there are doubtless layers that even I am not entirely conscious of, much as Tolkien described his own writing process.

We originally described the story as “The Hobbit (with bears) meets The Wizard of Oz (with penguins) meets Parzifal (with a griffin) meets The Voyage of St. Brendan (with the Leviathan), with a dash of Terry Pratchett’s Thud. Probably. Depending on what happens in the Ice City with the penguins. With gemstones inspired by Marbode of Rennes. I’m thinking there is something of The Silmarillion in the story soup as well. And probably some Pilgrim’s Progress.” I will be interested to hear what other influences readers discern, but one of my newer poets has for reasons unexplained started reading James Joyce, which I think is a clue.

C.M. MAYO: What’s next for you—and the Dragon Common Room?

RACHEL FULTON BROWN: Our next poem Draco Alchemicus is even more ambitious, with a new artist and a new stanza form. Think Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene meets Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis, with pirates and insights from Marshall McLuhan on how “the medium is the message” and “the electric light is pure information.” We are launching a crowdfund this summer to help promote our work, but you can get a preview of the illustrations and opening stanzas on our website (https://www.dragoncommonroom.com).

Our new artist Zé Nuno Fraga is an experienced comic artist from Portugal, who specializes in truly terrifying Christian meditations, not to mention having an ethereal way with light. Our team has both shrunk and grown, as the poetry has gotten more demanding and we have expanded our technical range. We spent six months researching, brainstorming, and practicing Spenserian stanzas before starting to write this poem.

The best thing about the poetry for me is the way it gives shape to my academic reading and writing. I find myself researching things I would never have thought to consider in depth—pirates and the spice trade and alchemy and modern economics, not to mention media studies and horse racing—while becoming attentive to things I encounter both in real life and online as at once symbols and story.

A friend asked me recently about what the digital environment of social media and streaming means, as compared with the printed novel or electric film. I said, “You just said it. It’s streaming”—and then my newest poet started posting in our Telegram chat the opening pages of Finnegans Wake—“riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay.” The opening scene of Draco Alchemicus is set in a casino by the bay where our newlywed couple is betting on the horses.

I’m thinking we’re going to need a bigger ark for the coming flood.

*

EXCERPT from Aurora Bearialis:

From Act III: The City

12

The Mayor of the Penguins ruffed his neck

and asked, “How come these strangers to our town?”

The guards replied, “We found them on their deck.

They climbed the Wall of Ice from base to crown!”

The Mayor turned with just a trace of geck:

“Do you denounce the seals as vicious clowns?”

“We seek the Light the albatross once spied.”

The Mayor squawked: “But how is that one pied?!”

13

“We rescued him from seals who called him fat.

They tortured him with fish he could not eat!”

“Why do you seek the Light?” the Mayor asked.

“To gaze upon its rhyme, celestial sweet.”

“The Light is not for unclean eyes of brats,

but only those whom riddles can’t defeat.”

Ulfilas grinned, his eyes narrowed to slits.

“No wizards nor their riddles match our wits!”

14

“You seek the Light, but it has come to you

upon the water where light meets the sky.

Tell me: can earth rejoice as angels do?

Can some birds swim like fish, or great fish fly?

The crystal door to heaven surrounds you.

The starry glass of Time is flowing by!”

His riddle fell to them as magic dice,

their destiny set down upon the ice.

15

The bears began to ruminate his words,

but crunches interrupted their deep thoughts.

“What tasty treats, such convivial birds!”

said Yuan with his mouth full. “Hits the spot!”

The Mayor and his courtiers gasped, perturbed.

The Magellanics cried, “What hast thou wrought?”

“How dare he!” “Seize him!” came great shouts of woe.

“We welcomed you as friends, but you are foe!”

16

The penguins gaped in horror as the bear

crawled up the altar, munching as he said,

“Who made these canapés? They’re yummy fare!”

The Mayor shook with anger, his wings spread,

but Panda did not even feel his stare

so hungry was his soul for their sea bread.

When—lo!—a beast with frightening, flaming jaws

swooped down and seized San Yuan in its claws!

—By permission of the editor, Rachel Fulton Brown.

*

To find your copy of Aurora Bearialis, visit Dragon Common Room Books.

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

Q & A with Christina Thompson on Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia

From the Archives: A Review of Pekka Hämäläinen’s The Comanche Empire