Another One Hundred Foreigners in Morelos:

José N. Iturriaga (and Yours Truly) in

Cuernavaca’s Historic Jardín Borda

Originally posted on Madam Mayo blog July 4, 2016

To see one’s own country through the scribbles of foreigners can be at once discomfiting and illuminating. Out of naiveté and presumption, foreigners get many things dead-wrong; they also get many things confoundingly right. Like the child who asked why the emperor was wearing no clothes, oftentimes they point to things we have been blind to: beauty and wonders, silliness, perchance a cobwebby corner exuding one skanky stink. And of course, there are things for foreigners to point at in all countries, from Albania to Zambia.

As an American I have to admit it’s rare that we pay a whit of attention to writing on the United States by, say, Mexicans, Canadians, the Germans or the French. True, we have the shining example of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, which every reasonably well-educated American may not have waded through but has at least heard of (and if you haven’t, dear reader, now you have.) But de Tocqueville’s tome is a musty-dusty 181 years old (the first of its four volumes was published in 1835, the last in 1840– get the whole croquembouche in paperback here.)

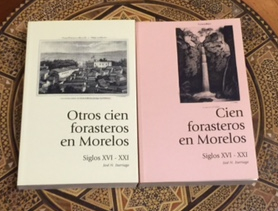

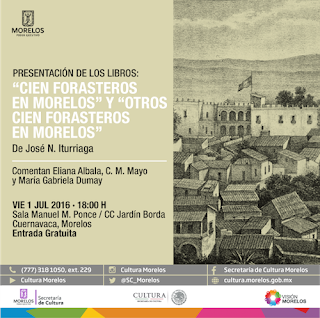

This past Friday, July 1, 2016, I participated in the launch of novelist and historian José N. Iturriaga’s anthology Otros cien forasteros en Morelos [Another One Hundred Foreigners in Morelos], the companion volume to Cien forasteros en Morelos [One Hundred Foreigners in Morelos], from the 16th to the 21st century.

(For those rusty on their Mexican geography, Morelos is a large state in central Mexico that includes Cuernavaca, “the city of eternal springtime,” which it actually is, and Tepoztlán, a farm town surrounded by spectacular reddish bluffs that, despite an influx of tourists from Mexico City and abroad, still has a strong indigenous presence, and has been designated by Mexico’s Secretary of Tourism as a “pueblo mágico.” The most famous resident of the state of Morelos was Revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata.)

The launch was held in the Centro Cultural Jardín Borda (Borda Gardens Cultural Center), an historic garden open to the public in downtown Cuernavaca– about an hour and a half’s drive from Mexico City.

As Iturriaga said in his talk, for almost forty years he has been studying the writings of foreigners on Mexico, precisely for the fresh, if not always kind nor necessarily accurate, perspective they offer on his own country.

I admire Iturriaga’s work, and his curiosity, open-mindedness, and open-heartedness more than I can say. It was a mammoth honor to have had an excerpt from my novel included in his anthology, and to have been invited to participate on the panel presenting his anthology. The other two panelists, whose work is also in the anthology, were poet, novelist and essayist Eliana Albala and journalist and poet María Gabriela Dumay, both of whom came to live in Cuernavaca in the early 1970s, political exiles from Pinochet’s Chile.

Mexican book presentations tend to be more formal affairs than those in US (the latter usually in a bookstore with, perhaps, a brief and informal introduction by the owner or a staff member. I have war stories.) In Mexico, in contrast, there is usually a felt-draped dais, always a microphone, and two to as many as five panelists who have prepared formal lectures about the book. The author speaks last, and briefly. Another difference is that the Mexican reporters, photographers, and oftentimes television cameras crowd the dais, lending the affair a glamor and gravitas rare for a US book presentation. Afterwards, there is a party with white-gloved waiters pouring “vino de honor”– in this case, for Iturriaga’s Otro cien forasteros en Morelos, whoa, mezcal.

>> Where to buy Otros Cien Forasteros en Morelos? I hope to be able to provide a link shortly.

Here is my talk for the panel, translated into English.

Dear José Iturriaga; fellow panelists, Eliana Albala and María Gabriela Dumay; everyone in this beautiful Centro Cultural Jardín Borda who made this event possible; Ladies and Gentlemen:

First of all, heart-felt congratulations to José Iturriaga on this extraordinary anthology in two volumes, a magnificent and opportune cultural contribution that, no doubt, required endless hours of reading, not to mention the tremendous labor of love that went into selecting and then translating so many writers.

Between the covers of this second volume, Otros cien forasteros en Morelos, I find my fellow Americans Jack London, Katherine Anne Porter, and John Steinbeck– among the most outstanding figures in US literature. There is also the great novelist who arrived, so mysteriously, from Germany: B. Traven; and artists such as Pedro Friedeberg; and distinguished historians such as John Womack, author of Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, Michael K. Schuessler, biographer of the eccentric poetic genius Pita Amor; and the Austrian Konrad Ratz, whose meticulous research on Maximilian von Habsburg was essential, in fact a parting of the seas, in our understanding of the personality, education, and politics of the Archduke of Austria.

In three words, José Iturriaga’s anthology is eclectic, fascinating, and illuminating.

It is a great honor for me to participate in this presentation and an even greater honor that this second volume, Otros cien forasteros en Morelos, includes excerpts from my novel, The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire. [In the anthology, excerpts are taken from the Spanish translation by Mexican novelist and poet Agustín Cadena, El último príncipe del Imperio Mexicano.]

My novel is about the grandson of Agustín de Iturbide,* Agustín de Iturbide y Green (1863-1925) whom Maximilian “adopted” in 1865, making this half-American two-year old, briefly, Heir Presumptive to the Mexican throne.

(*Agustin de Iturbide (1783-1824) led the final stage of Mexico’s war for independence from Spain, and supported by the Catholic Church, was crowned Emperor of Mexico in 1822, deposed in 1823, and executed in 1824. )

In the winter of 1866, Maximilian brought his court here, to the Jardín Borda. And since we are within those very walls and surrounded by those very gardens, in celebration of José Iturriaga’s work, I would like to invoke those foreigners of the past, that is to say, I would like to read the few very brief excerpts from the novel, The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, as they appear in this anthology.

This bit from the novel is the imagined point of view of José Luis Blasio, a Mexican who served as Maximilian’s secretary:

Depend on it: Maximilian is shepherding Mexico into the modern world— so José Luis Blasio, His Majesty’s secretary, has told his family and tells himself. And this is no small task when His Majesty must grapple not only with our backwardness and ingratitude, but that thorn in his side, General Bazaine. The rumor is that, abetted by his Mexican wife’s family, Bazaine schemes to push aside Maximilian; they aim to have Louis Napoleon make Mexico a French Protectorate with himself in charge— not that José Luis would give that a peso of credence. But José Luis does consider it an outrage, the latest of many, that he would wire a complaint that Maximilian has removed his court to Cuernavaca, rather than “attend to business in the capital.”

Yes, they are here in the Casa Borda amongst gardens and fountains, fruit trees, palm trees, parrots of every size and color— a world away from Mexico City. But does not Louis Napoleon go to Plombières and Biarritz? Queen Victoria, who has sterner blood, travels as far as Balmoral in the Scottish Highlands. Dom Pedro II of Brazil retires to his villa in Petropolis. And did not the empress’s late father, Leopold, absent himself from Brussels in the Château Royal at Laeken? It is natural that for the winter, His Majesty should hold court in a healthier clime.

But even here where he siestas in a hammock, drinks limeade from a coconut shell, and wears an ecru linen suit with an open-necked blouse, Maximilian’s work never ceases. It is a wide, rushing river that José Luis can only hope will not overspill its banks. In the past year, José Luis has come to appreciate the uncompromising necessity of working long hours; indeed, his eyesight, never strong, has deteriorated from so much reading in the dim of early mornings. Maximilian arises at four; his valet attends him, and though he might linger over breakfast, by no later than six, he is at “the bridge,” as he says, that is, his desk— or, as here in Casa Borda, a folding table on the veranda. His Majesty’s dispatch box is heavy, and growing ever heavier…

And now Pepa de Iturbide, daughter of the Emperor Agustín de Iturbide, godmother to Agustin de Iturbide y Green, and member of Maximilian’s court:

It is a holy miracle that she got a wink of sleep at all! So appalled she is by Maximilian’s whim to uproot the court to this hamlet two bone-jarring days travel up and down the sierra— good gracious, this is no time to abandon the capital, and go gallivanting about with butterfly nets and beetle jars! Matamoros is under siege; the whole state of Guerrero, from Acapulco to Iguala, is in thrall to guerrillas. And Pepa got it from Frau von Kuhacsevich, who got it from Lieutenant Weissbrunn, that whilst the empress was in Yucatan, Maximilian fancied a visit to Acapulco, but General Bazaine nixed it because it would have been impossible to maintain security for his person. That is the sum of things!

Oh, but in Mexico City Maximilian felt cramped, “an oyster in a bucket of ice,” he said. Over the past two months, the few times Pepa chanced to see Maximilian, he had spoken of the empress’s dispatches from Yucatan proudly but with— Pepa recognized it when she saw it— a glint of green. If Maximilian could not have his expedition to Yucatan, by Jove, he was going to go some place tropical! And Maximilian could not be outshone by his consort, oh no. A mere visit to Cuernavaca would not do; he had to serve himself the whole enchilada with the big spoon: an Imperial Residence with landscaping, fountains, an ornamental pond stocked with exotic fish, and furnishings and flub dubs aplenty, comme ça and de rigueur. Whom did he imagine he was impressing with this caprice? Poor Charlotte, exhausted after Yucatan. And as if the von Kuhacseviches were not already foundering in their attempts to manage the Imperial Household in Mexico City! As if the Mexican Imperial Army could offer its officers anything approaching a living wage! Or keep its depots stocked with gunpowder! It is a monumental waste of time, of effort, of money, and to boot, Casa Borda is a-crawl with cockroaches, beetles, earwigs, and moths— a bonanza for Professor Bilimek!

And now the Austrian Frau von Kuhacsecvich, Mistress (chief administrador) of the Imperial Household:

On the steps to the next patio, Frau von Kuhacsevich must pause to fan herself. Cuernavaca is not the Turkish bath of the hot lands, more, as Maximilian put it, an Italian May. Pleasant for the men, and Prince Agustín, perhaps, but a trial for those who must encase themselves in corsets and crinolines. Oh, poor Charlotte that her father has died, but Blessed Jesus, what would Frau von Kuhacsevich have done had she been obliged to wear mourning black! The thought simply wilts her. She is afraid her face has gone red as a beet. Her back feels sticky, and under her bonnet, she can feel her scalp sweating. Taking the bonnet off is out of the question: her roots have grown in nearly an inch— in all the rushing to and fro, there has not been a snatch of time to touch up the color.

An Italian May: in that spirit, for luncheon, Tüdos has concocted an amuse-gueule of olives, basil, and requeson, a cheese too strong to pass for mozzarella, but toothsome. In addition to coffee, he will be making a big pot of canarino: simply, the zest of lemons steeped as tea. Well, here it has to be made of limes, ni modo, no matter, as the Mexicans say.

Finally, Maximilian himself:

Here, this moment in Cuernavaca, one is happy: perfumes in the air, colors from the palette of Heaven, birds, flowering trees and vines and oranges, the music of the orchestra and of the fountains, this bone-warming sunshine…

Thank you.

We Have Seen the Lights: The Marfa Ghost Lights Phenomenon

Book Review: Our Lost Border: Essays on Life Amid the Narco-Violence, edited by Sarah Cortez and Sergio Troncoso

Find out more about

C.M. Mayo’s books, articles, podcasts, and more.