Still revising the introduction for my translation of Francisco I Madero’s Spiritist Manual of 1911… and the introduction is turning into a book itself… meanwhile, here’s a brief excerpt from a new bit about the Theosophists— it’s the part where I go through Madero’s personal library. (For those of you new to the blog, Francisco I. Madero was the leader of the Mexican 1910 Revolution and President of Mexico 1911-1913. His Spiritist Manual has never before been translated.)

. . . . One book apparently did not belong to Madero: Las últimas treinta vidas de Alcione, Federico Climet Terrer’s 1912 Barcelona translation of Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater’s Lives of Alcyone, inscribed to Sara Pérez Vd. de Madero, Habana, Oct 18 1918. (Sara Pérez, Widow of Madero).

Now, as we see in Madero’s own library, Spiritist and Theosophical ideas so overlapped and intertwined, it behooves us to venture a little ways down another rabbit hole for the answer to the question, Who, pray tell, was Alcyone?

Alcyone (and Other Lives) in the 20th Century

Greek answer:A star-nymph, daughter of Atlas and lover of Poseidon.

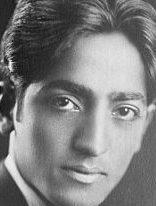

Literal answer: Jiddu Krishnamurti, a sickly Brahmin boy.

The Theosophists’ answer: As revealed by the Mahatmas, the vehicle for the Lord Maitreya, the Christ, the World Teacher.

It was C.W. Leadbeater who had discovered the adolescent Krishnamurti playing on a beach in 1909, identifying him as said vehicle by clairvoyant means. Alas, no story of the Theosophical Society gets told without the taint of Leadbeater’s, shall we say, intimate involvement with other young boys. Prior to this, in 1906, after vociferous complaints from parents, Leadbeater was obliged to resign. By 1909, however, his old friend and fellow Initiate before the Mahatmas, and expert on the Bhagavad-Gita, Annie Besant, had taken the reigns of the Theosophical Society and readmitted Leadbeater. In the Theosophical Society’s headquarters in Adyar, together Besant and Leadbeater arranged Krishnamurti’s care and education, and almost immediately, Leadbeater, by psychic means known only to himself, began researching the “Akashic” or astral records, on the lives of “Alcyone,” that is, the previous incarnations of Krishnamurti, in which Annie Besant appeared under the code-name “Heracles,” Leadbeater as “Sirius,” and various other Theosophists under various other names in mind-numbing permutations reaching back to 22,662 B.C. Mary Lutyens, daughter of the Theosphical Society’s benefactress Lady Emily Lutyens, and both childhood friend and biographer of Krishnamurti, in her memoir, To Be Young, recalled of the Lives of Alcyone, “a great deal of heart-burning and snobbery.”

“Are you in the Lives?” Became the question most constantly asked by one Theosophist of another, and, if so, “How closely related have you been to Alcyone?”

At night, by means of their astral bodies, Leadbeater took Krishnamurti to study with “Master Kuthumi,” that “Great White Brother” first introduced to this world by Madame Blavatsky, and in the morning, in his octagonal office, Leadbeater obliged Krishnamurti, whose English and writing skills were what one would expect of a little boy whose first language was Telegu, to record what he could remember of those lessons. Flash forward two decades to 1929, and the world traveling, English-educated World Teacher, venerated Head of Leadbeater and Besant’s creation, the 43,000 member-strong Order of the Star in the East, took the stage at Erde Castle in Holland before 3,000 members and, with a solemn salaam, dissolved that order. Krishnamurti did not deny being whatever they conceived him to be; he said:

“I maintain that Truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect… I do not care if you believe I am the World Teacher or not… I do not want you to follow me… You have been accustomed to being told how far you have advanced, what is your spiritual status. How childish! Who but yourself can tell you if you are incorruptible?… You can form other organizations and expect someone else. With that I am not concerned, nor with creating new cages, new decorations for those cages. My only concern is to set men absolutely, unconditionally, free.”

That, as one might guess, signaled the decline (though not the disappearance) of the Theosophical Society, as well as Annie Besant’s health. But fantastically, Krishnamurti’s career, unmoored from official disciples, continued to flourish. Like Teresa Urrea and the Niño Fidencio, Krishnamurti had a serene and childlike quality and an ability to draw and mesmerize crowds, but unlike them, Krishnmurti exuded an urbane polish, and he wrote some 30 books that articulated a philosophy of freedom and that appealed to such diverse figures as physicist David Bohm, writer Aldous Huxley, Indira Gandhi, and the Dalai Lama.

On YouTube, I found an old film of the white-haired Krishnamurti holding forth in a tent in Ojai, California, and what struck me was not anything he said—he sounded halting and vapid to my ears— but the faces of the hundreds of people sitting on the lawn before him, eyes shining, jaws slack. I could not help but think of Niño Fidencio— and the strange power I had seen in Francisco Madero in the films and photographs of his political rallies.

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

Why Translate? The Case of the President of Mexico’s Secret Book

Reading Mexico:

Recommendations for a Book Club of Extra-Curious

& Adventurous English-Language Readers

Biographers International Interview with C.M. Mayo:

Strange Spark of the Mexican Revolution