BY C.M. MAYO — October 4, 2021

UPDATE: This blog was then entitled Madam Mayo (2006-2022).

This blog posts on Mondays. This year, 2021, I am dedicating the first Monday of the month to Texas Books, in which I share with you some of the more unusual and interesting books in the Texas Bibliothek, that is, my working library. Listen in any time to the related podcast series.

Texas is giant in so many ways, including its literature. However, the literature on its Guadalupe Mountains is relatively sparse. This isn’t surprising when you consider how remote these mountains are—by car from El Paso, only after an hour and half do they rise up to their full splendor from the floor of the Texas desert. They make for a “sky island,” watered woodlands surrounded by the salty desert of what used to be a vast sea. There were never any towns in the Guadalupes’ wooded valleys; into the 19th century these valleys were inhabited by the Mescalero Apaches for seasonal hunting camps, until they were driven out by the U.S. Army, and the railroad tracks laid down across the desert, alongside the telegraph lines. Suffice to say, without the aid of fossil fuels, first coal, then oil, it was brutally difficult to travel over this region. Even today most travelers blow on by the Guadalupes at 80 miles an hour towards points west or east. As one who has served as an artist-in-residence in the Guadalupe Mountains National Park, I well know what glories (and not a few rattlesnakes) these mountains hold. I am at work on my memoir / portrait of Far West Texas but of course, others have written about the Guadalupes, and their works inform mine. Herewith, a few favorites from my working library:

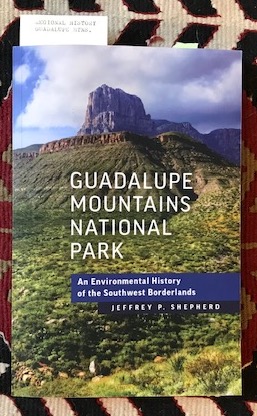

Jeffrey P. Shepherd’s Guadalupe Mountains National Park: An Environmental History of the Southwest Borderlands (University of Massachusetts Press, 2019) is the book I wish I’d had when I started my research some years ago. From the catalog copy:

“The Guadalupe Mountains stand nearly 9,000 feet tall, spanning the far western fringe of Texas, the border of New Mexico, and the meeting point of the Southern Plains and Chihuahuan Desert. Long an iconic landmark of the Trans-Pecos region, the Guadalupe Mountains have played a critical role for the people in this beautiful corner of the Southwest borderlands. In the late 1960s, the area was finally designated a national park.

“Drawing upon published sources, oral histories, and previously unused archival documents, Jeffrey P. Shepherd situates the Guadalupe Mountains and the national park in the context of epic tales of Spanish exploration, westward expansion, Native survival, immigrant settlement, the conservation movement, early tourism, and regional economic development. As Americans cope with climate change, polarized political rhetoric, and suburban sprawl, public spaces such as Guadalupe Mountains National Park remind us about our ties to nature and our historical relationships with the environment.”

*

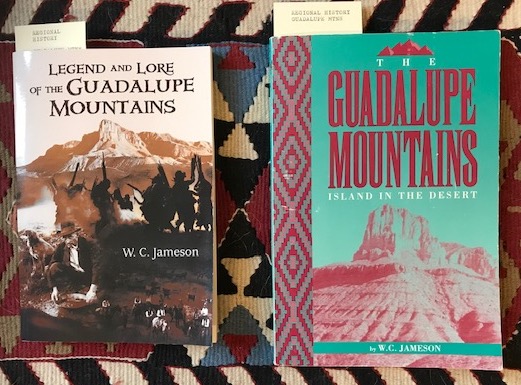

W.C. Jameson’s Legend and Lore of the Guadalupe Mountains (University of New Mexico Press, 2007) and The Guadalupe Mountains: Island in the Desert (Texas Western Press, 1994), with tales of Indians, wildest nature, secret gold mines and ghosts, are essential reading for any would-be Hollywood screenwriter.

*

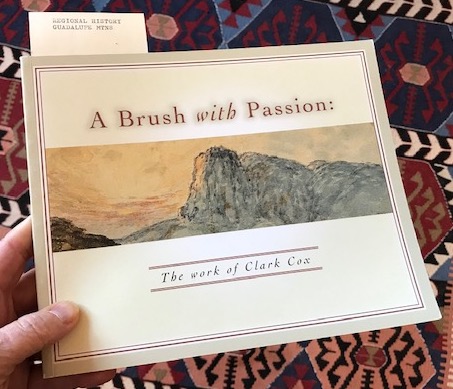

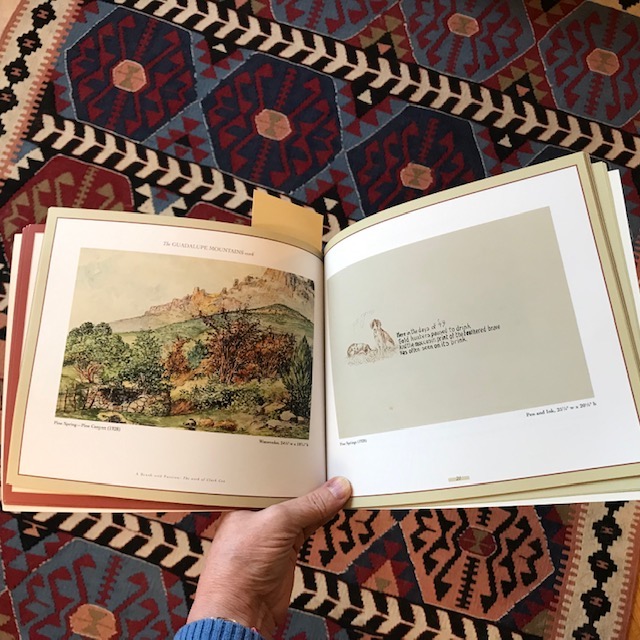

A Brush with Passion: The Work of Clark Cox, edited by Wendy Parish and Jeannie Sillis (Carlsbad Caverns-Guadalupe Mountains Association, 2003) is my personal favorite. Clark Cox (1861-1936) was a professional scene painter for opera and theater. For some time he worked out of New Orleans, then moved to Dallas, at which point he began to make annual pilgrimages to paint landscapes in the Guadalupe Mountains. His strike me as the kind of watercolors Beatrix Potter would have painted, had she ventured so far afield. And having hiked these landscapes myself, these many decades later, I so admire how Cox captured their subtle beauty.

*

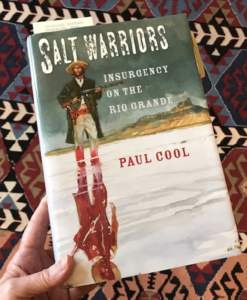

Paul Cool’s Salt Warriors: Insurgency on the Rio Grande (Texas A & M University Press, 2008) is a major scholarly history of the El Paso Salt War of 1877, a bloody conflict between newly-arrived Anglo businessmen and local Mexican salt harvesters. I had the honor of interviewing the author for this blog back in 2016.

*

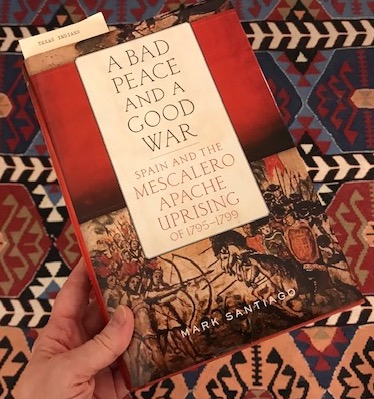

Mark Santiago’s A Bad Peace and a Good War: Spain and the Mescalero Apache Uprising of 1795-1799 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2018) is a superbly researched history of a war that had been, essentially, entirely forgotten. From the catalog copy:

“This book challenges long-accepted historical orthodoxy about relations between the Spanish and the Indians in the borderlands separating what are now Mexico and the United States. While most scholars describe the decades after 1790 as a period of relative peace between the occupying Spaniards and the Apaches, Mark Santiago sees in the Mescalero Apache attacks on the Spanish beginning in 1795 a sustained, widespread, and bloody conflict. He argues that Commandant General Pedro de Nava’s coordinated campaigns against the Mescaleros were the culmination of the Spanish military’s efforts to contain Apache aggression, constituting one of its largest and most sustained operations in northern New Spain. A Bad Peace and a Good War examines the antecedents, tactics, and consequences of the fighting.

“This conflict occurred immediately after the Spanish military had succeeded in making an uneasy peace with portions of all Apache groups. The Mescaleros were the first to break the peace, annihilating two Spanish patrols in August 1795. Galvanized by the loss, Commandant General Nava struggled to determine the extent to which Mescaleros residing in “peace establishments” outside Spanish settlements near El Paso, San Elizario, and Presidio del Norte were involved. Santiago looks at the impact of conflicting Spanish military strategies and increasing demands for fiscal efficiency as a result of Spain’s imperial entanglements. He examines Nava’s yearly invasions of Mescalero territory, his divide-and-rule policy using other Apaches to attack the Mescaleros, and his deportation of prisoners from the frontier, preventing the Mescaleros from redeeming their kin.

“Santiago concludes that the consequences of this war were overwhelmingly negative for Mescaleros and ambiguous for Spaniards. The war’s legacy of bitterness lasted far beyond the end of Spanish rule, and the continued independence of so many Mescaleros and other Apaches in their homeland proved the limits of Spanish military authority. In the words of Viceroy Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spaniards had technically won a ‘good war’ against the Mescaleros and went on to manage a ‘bad peace.'”

*

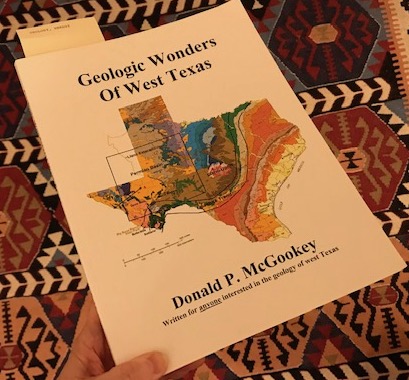

Last but not least of the favorites to mention, is Donald P. McGookey’s Geologic Wonders of West Texas (self-published, second printing, 2007). This is uber-nerdy geology, but essential reading for anything to do with the Guadalupe Mountains, for these are geologic wonders indeed. To quote McGookey, page 70:

“The Guadalupe Mountain rocks are of a very large and long barrier reef, the Capitan Reef. This type of barrier reef is very similar to the present day Great Australian and Belize Barrier Reefs. The continuity of sediments down the slope into the basin facies are the best found anywhere in the world. In places like McKitrick Canyon it is an easy hike from rocks of the top part of the reef to those deposited in the basin. Total relief between the reef and deeper parts of the basin is over 5,000 feet.”

*

Finally, two extra-crunchy videos:

Eleanor King’s video “Conflict Archaeology: The Untold History of the Buffalo Soldiers and the Apache in Texas”

*

This recent Zoom by archeologist Dr Bryon Schroder is not about the Guadalupe Mountains per se, but about cutting-edge research on paleolithic hunters in the larger Big Bend Region of Far West Texas. I include it here because it gives an overview of peoples who would have also hunted in the Guadalupe Mountains.

*

I welcome your courteous comments which, should you feel so moved, you can email to me here.

Selected Cabeza de Vaca Books, Part II:

Notes on Narrative Histories and Biographies

Journal of Big Bend Studies: “The Secret Book by Francisco I. Madero”

Notes on Artist Xavier González (1898-1993),

“Moonlight Over the Chisos,” and a Visit to

Mexico City’s Antigua Academia de San Carlos