This blog posts on Mondays. Second Mondays of the month I devote to my writing workshop students and anyone else interested in creative writing. Welcome!

> For the archive of workshop posts click here.

One of the gnarliest challenges in writing nonfiction is that oftentimes, no matter how thoroughly we do our reading and research, we just do not have the factual information to make an important scene come alive on the page. On the other hand, by its attention to specific sensory detail, fiction has the power to incite a “vivid dream”in the reader’s mind. But, by definition, aren’t we supposed to avoid fiction when we write nonfiction?

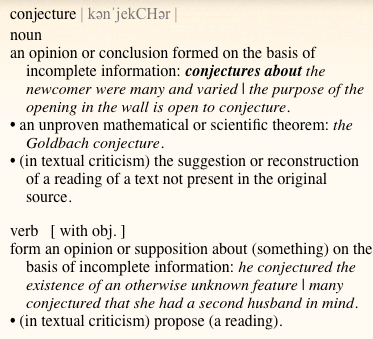

I write what’s called “creative nonfiction” or “literary journalism” — and this does not give me license to mislead my reader. What the adjectives ” creative” or “literary” mean is that I make use of various lyrical techniques in writing nonfiction. One of these is conjecture.

Conjecture is a powerful way to upfront, above-board, nada de funny-business, blend the magic of fiction into your nonfiction and so limber it up, stretch it out, let it breathe… and thus help your readers more clearly see a situation, a personality, animal, thing, a feeling, an interaction, or whatever else it might be that needs more depth, a star-gleam of vividness.

Foolishly, certain historians, la de da, just make things up, or, to say the same thing, without a shred of credible evidence, assert as fact what they would like to believe and/or what makes for the best story. And when these historians are found out, so much the worse for their reputations. And I say “foolishly” because those so-called “historians” could have honestly achieved the same effect for the reader, should that have been called for (sometimes it’s not), by instead offering their conjecture.

Academic historians tend to steer wide-clear of conjecture. That said, one of my favorite history podcasters, Liz Covart, host of Ben Franklin’s World, always ends an interview with an invitation to conjecture. And I am sure that you, dear writerly reader, can also offer some fine examples of exceptions.

On the other hand, many writers of creative nonfiction / literary journalism / popular history frequently make use of conjecture.

Think of it this way: We generally do not pick up an academic journal unless we are obliged to, while creative nonfiction is oftentimes the just the thing for the beach bag– and not necessarily because it is less intellectually nutritious.

Yeah, I go for intellectually nutritious beach reading.

In the following brief examples taken from works of creative nonfiction / literary journalism note how the author clearly signals to the reader that he or she is not asserting a fact, but offering conjecture.

Then Jesup got lucky. Abraham agreed to meet with him. He arrived at Jesup’s Fort Dade headquarters on January 31. The two men probably sat down in a rude, whitewashed office. An oil lamp would have provided flickering light. Jesup would have had on his dress uniform–lots of braid, and maybe some dangling medals. Abraham, in contrast, would undoubtedly have worn ragged deerskin, the sartorial legacy of fighting and hiding in the swamps.

––Jeff Guinn, Our Land Before We Die: The Proud Story of the Seminole Negro

Guinn’s clear signals to the reader that this is conjecture:

“probably”

“would have”

“maybe”

“would”

#

This had been a Columbian mammoth, the tracks circular, decayed, and toeless. There would be no scientific report on the find. We’d never be able to find these again or explain where they were, compass bearings too vague on this expanse, no GPS to drop a way-point. I walked alongside the tracks, and the mammoth rose up from the ground, its body filled in by my mind’s eye. It didn’t seem to notice me, it was focused ahead, tusks swaying back and forth as it traveled. It had hair, with rough brownish or gray skin visible underneath, but it was not woolly like its northern cousins…

––Craig Childs, Atlas of a Lost World: Travels in Ice Age America

Childs’ clear signal to the reader that this is conjecture:

“filled in by my mind’s eye”

#

In my dream I was walking a rural road in Aquitaine, high above a river, when my attention was drawn to something in the roadside woods–mound, barrow, some small heap of disturbed earth. On investigating this I found a partly distinterred Neanderthal skeleton, one humerus and a femur faintly daubed with red. Quite improbable, my waking mind told me…

— Frederick Turner, In the Land of the Temple Caves

Turner’s clear signals to the reader that this is conjecture / fiction:

“In my dream”

“Quite improbable, my waking mind told me”

Still, the old beauty sat on before her glass of wine, nursing it as she may have been nursing her memories. She was old enough, I judged, to have seen it all, as we say: the Great Depression when ordinary Parisians slept out on the portico of the Bourse; the fall of France and the Occupation; Algeria and de Gaulle’s triumphant return to power; the vandalizing of the city by Pompidou; the new age of the terrorist… She didn’t seem to be at all captive to some senescent trance but instead attuned to something not evident, listening maybe like the Venus figure of Laussel.

— Frederick Turner, In the Land of the Temple Caves

Clear signals to the reader that this is conjecture:

“as she may have been”

“I judged”

“maybe”

#

And at some immeasurably remote time beyond human caring the whole uneasy region might sink again beneath the sea and begin the cycle all over again by the slow deposition of new marls, shales, limestones, sandstones, deltaic conglomerates, perhaps with a fossil poet pressed and silicified between the leaves of a rock

—Wallace Stegner, Beyond the Hundreth Meridian (p.169)

Clear signals to the reader that this is conjecture:

“might”

“perhaps”

He might see, as many conservationists believe they see, a considerable empire-building tendency within the Bureau of Reclamation, an engineer’s vision of the West instead of a humanitarians, a will to build dams without die regard to all the conflicting interests involved. He might fear any bureau that showed less concern with the usefulness of a project than with its effect on the political strength of the bureau. He might join the Sierra Club and other conservation groups in deploring some proposed and “feasible” dams such as that in Echo Park blow the mouth of the Yampa, and he might agree that considerations such as recreation, wildlife protection, preservation for the future of untouched wilderness, might sometimes outweigh possible irrigation and power benefits. He would probably be with those who are already beginning to plead for conservation of reservoir sites themselves, for reservoirs silt up and do not last forever, and men had better look a long way ahead when they begin tampering with natural forces.

–Wallace Stegner, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian (p. 361)

Clear signals to the reader that this is conjecture:

“as I imagine”

“could have”

“perhaps”

“He might”

“He would probably”

#

Alas, I do not have my copy on hand to pluck out some choice quotes, but Nancy Marie Brown’s The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman is the most masterful example I have yet found of an historian using conjecture, and to brilliant effect. In this page-turner of a book Brown spins out the thousand-year old story of Gudrid the Viking who sailed from Iceland to Greenland, and to North America and, in her old age, made a pilgrimage to Rome. There is so much of value in The Far Traveler, both for learning about its subject (Icelanders; medieval life at the pioneer-edge of European settlement) and about the craft of writing itself. I would suggest that you buy a paperback copy, and read The Far Traveler with your writer’s eye, scribbling in your notes. (If you can get a fine first edition hardcover with the dustcover, keep it fine–out of the sun– and hang onto it!)

#

Finally, an example from own longform essay of creative nonfiction, “From Mexico to Miramar or, Across the Lake of Oblivion”:

Here, I supposed now, Maximilian must have imagined that he would return to his glittering dinner parties, and simpler, bachelors’ evenings of billiards, smoking, cards. He would write his memoirs of Mexico. Travel: why not an expedition to the Congo? Or Rajastan? And I had read somewhere that Maximilian had told someone (was it Blasio?) that one day he should like to fly balloons. This parterre would be the perfect place for a launch:

Late August 1867. A summer’s day, sparkling, sun-kissed sea. He is well again, he has put on weight. His entourage in tow, he strides across the gravel and steps into the basket of a billowing, parrot-green montgolfier emblazoned, of course, with “MIM.” And it lifts, up and yonder over the shining white tower of Miramar. From the basket sandbags splash to the sea — and it rises ever higher, ropes trailing.

A picnic in the clouds: chilled champagne, tiny toasts spread with foie gras.

“What’s so funny?” A. said.

I sighed, and put down my coffee cup. “It ended a little differently.”

My clear signals to the reader that this is conjecture:

I supposed now, Maximilian must have imagined

I sighed…. “It ended a little differently.”

[as explained previously, Maximilian was executed by firing squad]

#

So, where in your nonfiction manuscript does it make sense to use conjecture? You’re the artist! But I would whisper my little suggestion to you that it might be a place where, though you have little or nothing to go on, you would underscore the importance of a person (or some aspect of his personality or manner), animal, object, incident, or scene, and so invite the reader to slow down and pay special attention.

It can be, after all, a delightful thing to offer your conjecture.

#

For some practice with conjecture (as well as many other aspects of creative writing) check out “Giant Golden Buddha” and 364 More Five Minute Exercises,” which is available for free on my website. A few examples:

“Future Neighborhood”

Describe your neighborhood as you would expect it to appear 10 years from now.

“Take the Day Off”

If you were to take today off, what would you do? What would your brother or sister do? Your boss? Your neighbor? Smokey the Bear?

“Who Went to McDonald’s?”

This exercise is courtesy of novelist Leslie Pietrzyk.

Who is the most unlikely person— living or dead, famous or non— you can think of to be in a fast food restaurant? Okay— that person just walked into McDonald’s (or choose your own fave). Why are they there and what happens?

From The Writer’s Carousel: Literary Travel Writing

Great Power in One: Miss Charles Emily Wilson

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.