UPDATE: This blog was then entitled Madam Mayo (2006-2022).

This blog posts on Mondays. Second Mondays of the month I devote to my writing workshop students and anyone else interested in creative writing. Welcome!

> For the archive of workshop posts click here.

DUENDE

Duende is a Spanish word that might be translated as “sprite” or “fairy.” But for poets and other artists, no one has evoked, if not quite explained this rare, magnetic quality in art, so well as Federico García Lorca in his poetry and in his essay, “The Theory and Play of the Duende.”

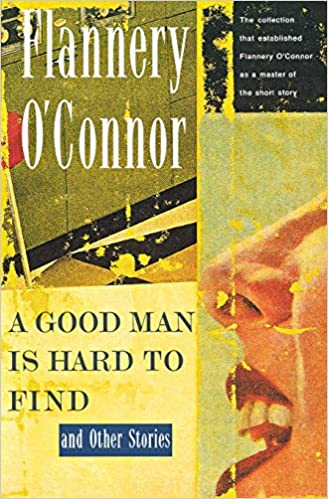

Who and what else has duende? Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Tolstoy— and especially broad sections of War and Peace. Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker— all of it. William Butler Yeats’ poetry. Charlie Chaplin’s silent movie “The Pilgrim”— especially the final scene at the US-Mexico border. In a time closer to our own, Flannery O’Connor’s fiction oozes duende.

Do you already have your own list? If not, I can recommend making one as a more than illuminating exercise.

ELB

Oftentimes writing with duende aims to épater les bourgeois, shock the middle class, as those poètes français d’autrefois so loved to do. The danger is that, alas, that épater stuff— I call it ELB for short— more often than not lacks duende. And ELB without duende is so old hat, you can vacuum it up along with the dust bunnies and dead flies.

In plain English, I label as ELB without duende those scenes, imagery, and lines of dialogue that don’t do squat, other than reveal the author’s rude jones to appear too cool for school. Entre nous, dear writerly reader, alas, more often than not, ELB might as well also stand for Easy Lazy Bullcrap.

Or, say, Egregiously Louche Buffalocrap.

“To get into the best society, nowadays, one has either to feed people, amuse people, or shock people – that is all!”

― Oscar Wilde, A Woman of No Importance, 1893

It’s 2020. Scandalizing Grandma? She’s probably got three tattoos and you don’t want to guess what she’s watching on YouTube.

Green hair? Black fingernails? Chainsaw massacre? Yawn.

That said, Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find” is one of the finest short stories yet written in the English language and it’s totally ELB, in the original sense. It is deeply weird, crisp, charming, punch-funny, and horrifying for, in the end– trigger warning!– Grandma gets offed by the mass murderer. It works. Why? Did I mention, it is deeply weird, crisp, charming, and punch-funny? O’Connor had so much duende, Dr. Jung would not have been surprised that her family’s farm in Milledgeville, Georgia, where she wrote so much of her fiction, was called Andalusia. “A Good Man is Hard to Find” appeared in 1953, and it still twirls the wig of just about everybody who reads it.

Religion is not my rodeo. However, I can recommend this fascinating interview with literary scholar Dr Jessica Hooten Wilson about how Flannery O’Connor’s Catholic faith informs her writing (the camera is a little shaky, so you might want to focus on just the sound):

More about duende and ELB anon.

P.S. You can find the archive of workshop posts here. Again, I offer a post for my workshop students and anyone else interested in creative writing on the second Monday of every month.

The Book As Thoughtform, the Book As Object:

A Book Rescued, a Book Attacked, and Katherine Dunn’s

Beautiful Book White Dog Arrives

One Simple Yet Powerful Practice in Reading as a Writer

Waaaay Out to the Big Bend of Far West Texas,

and a Note on El Paso’s Elroy Bode

#

Find out more about C.M. Mayo’s books, shorter works, podcasts, and more at www.cmmayo.com.